80th Anniversary of the Atlantic Charter

As a History major at Trinity College, Connecticut, Michael Kluger always knew more about the Atlantic Charter than most of us – in fact virtually all of us. A puzzled look was the usual expression that came over people’s faces when confronted with the question: “What do you know about the Atlantic Charter?”

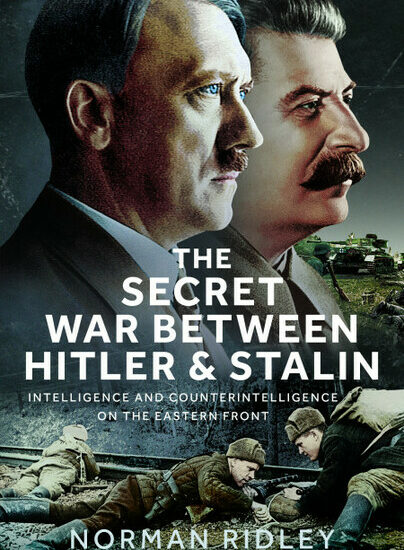

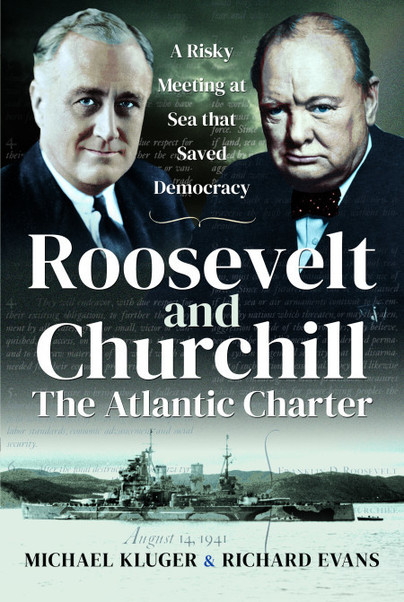

Hopefully, there will be fewer now for two main reasons: First, Michael and I decided to collaborate on a book called ‘Roosevelt and Churchill: The Atlantic Charter – a Risky Meeting at Sea that Saved Democracy” and Second: Because the President of the Unites States and the Prime Minister of Great Britain suddenly opted to resurrect the Charter and update it when they met in the county of Cornwall, UK in June this year.

Anyone wanting a little help in publicising a book could not do much better than have Joe Biden and Boris Johnson thrust the title into the public arena so, no matter how unaware they might have been in helping our cause, we can only say ‘Thank you!’

Our intention was, and remains, to throw a detailed light on a momentous moment in history that occurred over four days – August 9 – 12, 1941 – when the 20th Century’s two greatest leaders met officially for the first time on their war ships anchored at Placentia Bay off the coast of Newfoundland.

The American President and the British Prime Minister had been corresponding by cable and letter ever since Churchill had entered No 10 Downing Street in May the previous year. But both men felt that a face to face meeting was vital as Hitler’s shadow grew ever larger. It was impractical for many reasons for FDR to make a trans-Atlantic journey but Churchill, desperate to strike up a proper friendship with a man who held the future of Britain and its Commonwealth in his hands, was prepared to go to any lengths to achieve his goal.

So our book starts like the adventure story it was – a hair raising trip across the German U-Boat infested North Atlantic that saw HMS Prince of Wales ploughing through 20 ft waves as a mighty storm left the battleship exposed to attack after all three of the Destroyers which were supposed to provide protection, fell behind, unable to deal with the weather.

Churchill who, all his life, had chased danger and adventure, was ebullient, relishing action instead of being bound to his desk in Whitehall. As soon as contact was made on a misty summer’s morning, with Churchill being piped aboard the cruiser SS Augusta, the talking – and the scribbling of what would morph into the Atlantic Charter – began.

The two men jotted down ideas on the backs of menus at dinner & aired their thoughts with the senior staff they had brought with them – men like FDR aid Harry Hopkins and Assistant Secretary of State Sumner Wells on the American side and Sir Alexander Cadogan, who led the British contingent. The final document, normally encased in the Archives at Churchill College, Cambridge and which we were able to access, was shown to President Biden and Prime Minister Johnson in Cornwall. It comprises a single sheet of paper, hastily typed with minor mistakes and festooned with Churchill’s corrections scrawled in fading red ink.

Once it was completed to everyone’s satisfaction, it was telegraphed to Deputy Prime Minister Clement Attlee in London for Cabinet approval before being broadcast on the BBC two days later as the Prince of Wales carried Churchill home. Strangely, it was never signed.

After explaining how it all happened, we offer mini-biographies of the leading characters in this historic drama – people who played vital roles in assisting the two leaders at the time as well as later once Roosevelt was able to bring the United States into the war following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in December that year. Apart from the aforementioned Hopkins, Welles and Cadogan, there was General George Marshall whose Marshall Plan dd so much to put Europe back on its feet after the war; Lord Beaverbrook, the rumbunctious Canadian newspaper magnate who became Churchill’s Minister of aircraft production and Air Vice Marshall Wilfrid Freeman whose expertise as a World War One fighter pilot enabled him to guide the nuts and bolts of getting the Spitfires and Hurricanes off the production line and into the air so that they could win The Battle of Britain. Beaverbrook made all the noise and chivied everyone into action but, behind the scenes, it was the little know figure of Freeman who played an even bigger role in ensuring that Churchill had the wherewithal to beat the Luftwaffe in 1940.

As a final chapter, we have added the story of Randolph Churchill. Winston’s brilliant but socially impossible son whose liquor-fueled temper tantrums ruined innumerable dinner parties. The fact that his behavior defined him was a tragedy because there was no sharper political observer during the pre and post war years and his influence on his father, stormy though it frequently was, influenced the Prime Minister to a far greater degree than is realized. Randolph did not travel to Placentia Bay but, throughout this story, he loomed large in the hinterland of his father’s mind.

– Richard Evans, August 2021

You can order a copy of Roosevelt and Churchill The Atlantic Charter here.