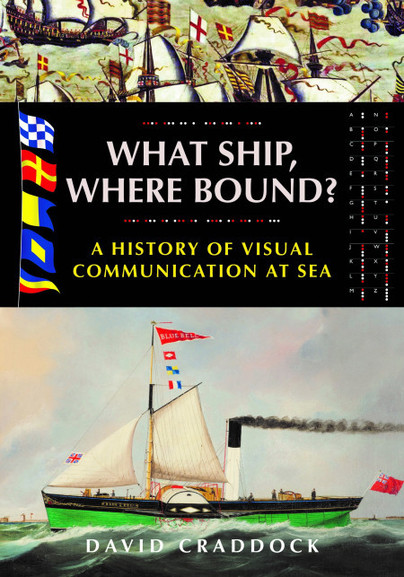

Author Guest Post: David Craddock

The starting point for this book was my own experience as a young cadet with P&O in the early 1960s. During bridge watches at night, and often during the day, it was quite routine to call up passing ships with the Aldis signal lamp and I remember the 3rd Officer during the First Watch (8-12) one night asking me to ‘call up that ship’. “What do I say?” I ask him. “Start with ‘What Ship, Where Bound?’” came the reply. And so I did, almost certainly with some first-time nerves; sending Morse by lamp is easy but reading it takes practice and I cannot recall with clarity what the outcome was, but the opening question has stayed with me and eventually became the title of this book.

The second driver for the book has been my subsequent career as a graphics and exhibition designer in the museums and heritage sector, often with an emphasis on our maritime heritage – I was lucky enough, for example, to work on the iconic Titanic project in Belfast. Having a close professional engagement with visual communication, flag signalling at sea with its long history has always been a background interest which has attracted a number of writers over the years to all of whom I owe a debt and gladly acknowledge. What I wanted to do with this book was to set a history of all forms of visual communication: flag signalling, semaphore and light signalling in the context of current usage and the ways in which, particularly in the case of flags, some signals have become embedded equally in our maritime heritage and popular culture.

One such signal is Admiral Lord Nelson’s famous signal at Trafalgar. Everyone can bring it to mind; what I have tried to do in a short section on ‘Decoding the Trafalgar Signal’ is to explore what Nelson intended and how his signal in the moments before the battle has been adopted for everything from recruitment posters in both World Wars (see below) to England’s attempts to regain the World Cup. I also highlight the forensic work of Lt Col W G Perrin who, as Admiralty Librarian in 1908, showed that popular depictions of the Trafalgar signal published to mark the centenary of Nelson’s victory had used the wrong code. To find out how the mistake came about you will have to read the book!

(National Archives INF3/163)

Flag signalling, unlike semaphore and, later, light signalling, was developed by and for seafarers with the primary aim of manoeuvring fleets at sea. Individual commanders in chief would champion their own preferred system, introducing flags to their own design with inevitable rivalry and often unintended consequences, at least until the publication of The Signal Book for the Ships of War based largely on the work of Admiral Lord Howe, in 1799.

With the exponential growth in maritime trade and the transition to steam in the early decades of the 19th century, there was equal rivalry among competing proposals for the commercial market. It was not until 1857 that the Commercial Code published by the British Board of Trade began to gain international recognition, though not without resistance from adherents of Marryat’s code. A timeline at the beginning of the book traces the long evolution of flag signalling from antiquity to the International Code that we would recognise today, even if only on a cushion cover, mug design or tee-shirt.

(Norfolk Museums Service Time and Tide Museum)

The transition to steam in the Royal Navy and the changing requirements for visual signalling to control the ever-more precise manoeuvres of ‘steam tactics’ occasioned fierce debates within the Service. Further unintended consequences tested the limits of flag signalling and are explored in the book. One such was the success and failure of signalling at the Battle of Jutland in May 1916 which is examined in some detail through a careful analysis of the fleet signal logs contained in the Official Despatches following the battle. Out of that study emerges some poignant exchanges by semaphore which lay outside the routine signalling of course alterations and deployment by flag and light. Some of those exchanges are included in the book and offer a glimpse of more personal interactions amid the smoke and confusion of a fleet action in poor visibility.

Some of the semaphore exchanges at Jutland may have been made using hand cranked mechanical arms on a short pedestal but many, probably most, would have been made at close range with hand flags for which purpose flag ‘O’ (yellow/red diagonal) had been adopted in 1901. At last arms and flags were doing what machines had been contrived to imitate for nearly a century! Light signalling by Morse code went through a similarly protracted process with rival opinions as to how best to convert Samuel Morse’s telegraph code into light signals. One camp favoured fixed red and white lights in various permutations; the other, flashing white lights of different duration and interval. Passionate arguments were made by advocates of both systems, all captured in correspondence which survives in Admiralty records now in the National Archives (ADM 116/64). They are a rich source both of the practical details and of late 19th century social attitudes within the Royal Navy, with questions as to the wisdom of relying on ‘an irresponsible signalman’ to read Morse code, while an officer though untrained in signalling could understand signals made by a fixed light system ‘…using his common sense’ – and by, implication, more reliably. Such are some of the stories that animate this book.

David Craddock

February 2021

You can order a copy here.