Author Guest Post: Geoff Scargill

Stars of the Victorian Era

The Victorian Era, an age when Britain ruled the world, threw up a stream of great characters. Even if you haven’t been interested in puff-puff engines since you were little and don’t read Thomas the Tank Engine before you go to sleep any more, the chances are that you’ve heard of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, if only because of his exotic name. He built the Great Western Railway with its own broad-gauge tracks, which meant that when you travelled to the south-west from anywhere else in Britain you had to get out at Exeter and board one of Brunel’s wider trains. He was one of the supremely confident men who captured the spirit of the age. If they had an idea, they did it.

George Hudson was another larger-than-life character. At the age of 27 he nursed his great-uncle, who then left him two and a quarter million pounds at today’s rates. He achieved great things, such as joining Edinburgh to London by rail, and became an MP. But his money didn’t go far in financing his dodgy property speculations – he didn’t bother about actually having the money that he was investing. After a lifetime of juggling and bribery he fled to France to avoid a mountain of fraud cases and died bankrupt and disgraced. His behaviour was a national scandal. Charles Dickens once said: “Whenever I hear Mr. Hudson’s name, I am disposed to throw up my head and howl. “

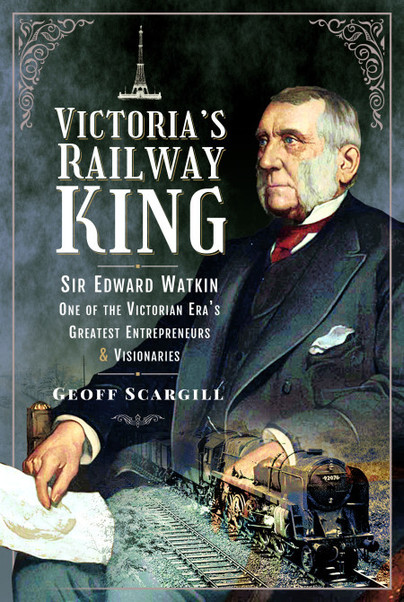

Sir Edward Watkin MP was another Hudson – except that he was honest. Supremely confident and a risk-taker, he took on schemes that everyone said were impossible and often succeeded. His rescuing of many bankrupt railway companies earned him the nickname ‘The Railway Doctor’.

But his failures were spectacular:

In 1880 he started to dig a Channel Tunnel from Dover. He had got two miles towards France before the government panicked and stopped him. They were frightened that the French would invade Britain through Watkin’s hole in the ground.

In 1896 he opened a tower in London to out-Eiffel the rival in Paris. It had reached 155 feet when the money ran out and in 1905 it was sold for scrap. But the park that was the setting for the tower became Wembley Stadium in 1921. When the site was excavated in 2004 for the building of the present stadium the foundations of Watkin’s tower were revealed for the first time in 93 years. They are still there, under the present pitch.

Other grand schemes never left the drawing board, either because there was no money or the authorities lacked vision. Watkin wanted to join Scotland to Ireland by a railway tunnel. He was laughed at for that, but it’s an idea that’s being looked at again today. He wanted his Channel Tunnel to provide a rail link from the Britain to India. Not so crazy as it sounds. Railways were the fastest way to travel and carry goods before planes were invented and the Chinese have now started a rail link to every major European country, including to London. He wanted to double the capacity of trains by introducing double decker carriages. It’s worked in Switzerland and Germany but not here.

What of Watkin’s successes? He was an MP for 25 years. His Great Central Railway was the last mainline from Manchester to London till High Speed One. He created the biggest fishing port in the world, Grimsby, and a holiday resort next to it, Cleethorpes. He helped the British government in negotiations that led to the founding of a new country, Canada. He founded the first credit union bank to encourage his employees to save for their future. And he led the campaign to build the first public Parks for the People in the hell-holes of industrial Manchester and Salford, when ordinary families had nowhere beautiful to sit and relax and let their children play. The first Eco-warrior?

But Watkin never knew about his last triumph, involving a four million pound lost masterpiece, since it happened 78 years after he died in 1901.

Now the details of the life of this amazing man – including revealing for the first time what drove him always to have to be top dog – are revealed in a new Pen & Sword book ‘Victoria’s Railway King’, to be published at the end of March.

Geoff Scargill

Available here.