Author Guest Post: Jaap Jan Brouwer

THE GERMAN WAY OF WAR. A LESSON IN TACTICAL MANAGEMENT

The German Army lost two consecutive wars and the conclusion is often drawn that it simply wasn’t able to cope with its opponents. This image is constantly reinforced in literature and in the media, where seemingly brainless operating German units led by fanatical officers predominate. Nothing was as far from the truth. The records show that the Germans consistently outfought the far more numerous Allied armies that eventually defeated them: their relative battlefield performance was at least 1.5 and in most cases 3 times as high as that of its opponents. The central question in this book is why the German Army had a so much higher relative battlefield performance than the opposition. A central element within the Prussian/German Army is Auftragstaktik, a tactical management concept that dates from the middle of the nineteenth century and is still very advanced in terms of management and organization. In this series of blogs we will have a closer look at the key elements of Auftragstaktik and cases that will illustrate the effects of these elements in the reality of the battlefield. In this part of the series we focus on leadership.

LEADERSHIP

One of the key elements of the high battlefield performance of the German army was leadership. In the vision of the German army as laid down in the concept of Auftragstaktik, officers and their units had to develop a maximum amount of their own initiative in order to be able to respond to unexpected situations. This made the necessary demands on the leadership style and the officers’ corps.

Officers and non-commissioned officers alike were expected that they

-

could motivate their men

-

create a sense of trust and security in the unit

-

were able to make / socialize the men to a team (to form a Kampfgemeinschaft), to enter into a dialogue with and get connected with their entrusted men

-

were authentic in their attitude and showed authentic interest in their men

-

were responsible for the personal and professional development of the individual soldier

-

could connect their men could on the ‘why’, not just on the ‘what’ and ‘how’

-

explore in person the battlefield and enemy positions

-

had the ability to quickly analyse complex situations, formulate answers and act accordingly

-

had the discipline to go through subjects from start to finish

-

take the initiative

-

could communicatie efficiently

-

could make their team think and act unambiguous.

These requirements played an important role during training and were the criteria for promotion. Personal qualities – a good character and strong will – were one of the most important criteria for becoming an officer.

Officers were trained at the Kriegsakademie and the Kriegsakademie did not provide ‘school solutions’, everyone could contribute his idea for the solution of a specific tactical situation, creativity was stimulated. This connected to the reality of the battlefield where nothing goes conform the plan and sudden shifts or incidents are likely to occur. Playing wargames, students were tested for flexibility in thinking and leadership, a free exchange of ideas was key. The cadets were also taught not to follow orders ‘when justified by honour and circumstances’.

The Germans found good personal relationships and an atmosphere of openness and trust within the vertical hierarchy of great importance. An important reason was that through open communication the higher echelons could keep an eye on the functioning of the various units and their commanders.

The attention given to the position of (non-commissioned) officers and the relationship with their men, made that a American study in which more than 10,000 prisoners of war were interviewed, concluded that “almost all non-commissioned officers and officers at the level of the company during the campaign in West- Europe were considered brave, efficient and compassionate by the German soldier”. A better compliment is hardly conceivable.

American Army

-

The American army had no common view of the role of officers and the way in which they had to be trained or what the ‘end product’ should ultimately be, each institute (Westpoint. Fort Leavenworth et cetera) filled in its curriculum in its own way

-

The Americans were inspired by the German system but there were serious misinterpretations, especially of the training system: the Americans supposed the German created a officers caste (a lasting misinterpretation: see movies and documentaries)

-

the American officers’ caste system thus created caused serious problems between officers and men, described by social studies after the war as ‘a yawning social chasm‘

-

cadets had to learn the theory and the formulated answers for tactical problems by heart, they had been taught that the solution of a tactical problem could be found in the manual of the training, the school solution was the norm, there was no room for discussion or own ideas

British Army

-

In general: the British army had ‘an excess of bravery and a shortage of brains’ (Air Marshall Tedder)

-

The British class system was clearly recognizable reproduced in the structure and culture of the army and the position of officers

-

The British command concept (if any) was strictly hierarchical, rigidity was the guideline

-

British officers were less well trained than their German counterparts, the British officer generally functioned at the level of the German non-commissioned officer (!)

-

The loss of their officer decapitated units, stopped them in their tracks, because the men did not know what to do and waited for fresh orders

-

The lack of adequate training meant that the British were forced to fall back on rigid, linear formations, which attacked enemy positions in consecutive waves not only in the First, but also often in the Second World War

Apart from the above, British and American higher level officers had the tendency to lead from behind (chateau general ship), in stead up front as did the German army.

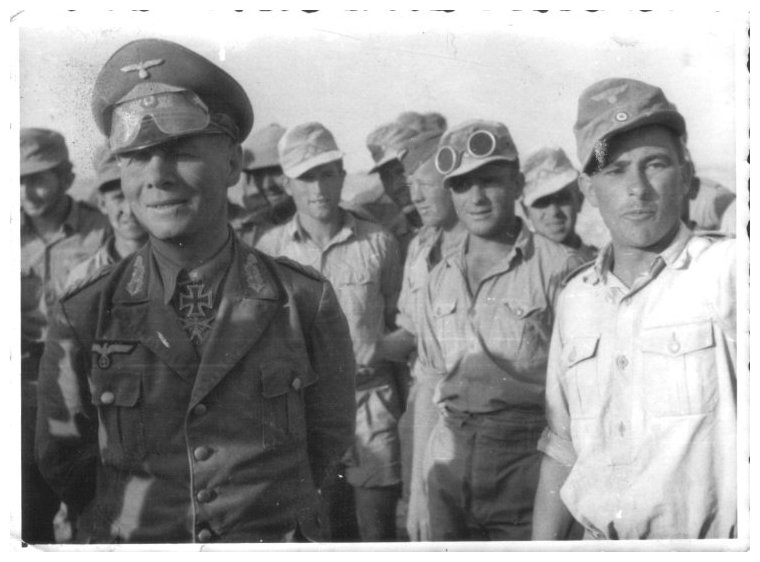

Being up front and leading up front was the norm in the Prussian/German army. Here we see Rommel with the men of 2. Abteilung Flakregiment 33 in 1942, Generalleutnant Walther Hörnlein following the advance of his forward units standing on the hood of his Sd.Kfz 251 during one of the first days of Fall Blau, the German summer offensive of 1942 and Guderian in France in 1940. In the words of Patton: ““For a commander there is no substitute to his own eyes”.

Being up front and leading up front was the norm in the Prussian/German army. Here we see Rommel with the men of 2. Abteilung Flakregiment 33 in 1942, Generalleutnant Walther Hörnlein following the advance of his forward units standing on the hood of his Sd.Kfz 251 during one of the first days of Fall Blau, the German summer offensive of 1942 and Guderian in France in 1940. In the words of Patton: ““For a commander there is no substitute to his own eyes”.

You can preorder a copy of The German Way of War here.