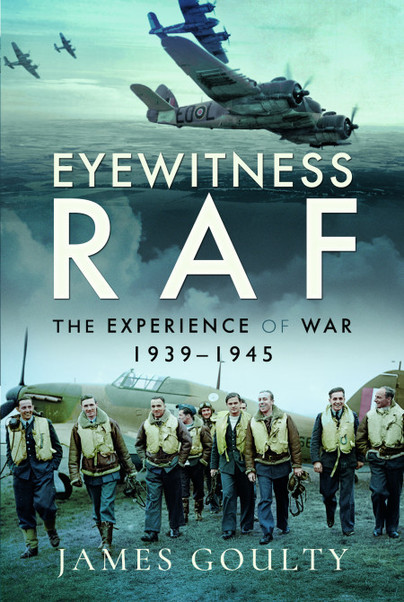

Author Guest Post: James Goulty

An Overview to the New Book:

Eyewitness RAF: The Experience of War 1939-1945

In his forthcoming book: ‘Eyewitness RAF,’ military historian and author, James Goulty, discusses the experiences of men and women who served with the wartime RAF. On mobilisation in 1939, RAF strength was 117,890 and this was rapidly increased by the addition of around 58,000 reservists and auxiliaries, albeit substantial numbers of these lacked training. From this relatively humble beginning, a large wartime force emerged that served around the globe. By 1944, when wartime recruiting ceased, approximately 1.2 million men and women were serving with the RAF, seventy percent of who were employed in non-flying trades. This highlights the immense effort that was required to support operational units. In contrast, trained pilots and aircrew held an elite status, not least because they were highly motivated and only five percent of those that applied for aircrew training were successful. As former bomber pilot and POW, Wing Commander Ken Rees, observed, aircrew were ‘hot stuff.’

The emphasis of the book is on life at squadron level and below, based around the personal experiences of a variety of men and women. Chapter one, covers recruitment and training, including what motivated individuals to enlist. Flying in the 1930s and 1940s held tremendous appeal and glamour, and many were attracted by the technical nature of the RAF. It also outlines the invaluable contribution of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF), as by 1945 women had become involved in numerous trades.

Bombing operations feature in chapter two, including the experience of Harry Blee, a flight engineer on Liberator bombers in the Far East, a theatre that is often overlooked. He went on to obtain a permanent commission before retiring as a wing commander in 1975. Naturally, Bomber Command’s prolonged offensive against Nazi Germany looms large, and the chapter outlines the increasing technological sophistication that this entailed through the eyes of those that served. Important issues are raised such as consideration of ‘Lack of Moral Fibre’ cases, LMF being the official term used to brand personnel deemed of displaying cowardice.

Fighter pilots are covered by chapter three, which illustrates the characteristics they required, plus the many different roles performed by fighter aircraft. For example, in North Africa, Spitfire pilots, including Tony Tooth, whose memories feature in the book, were aghast when they found that they had to act in the fighter bomber role instead of as thorough bred fighters. In discussing the various experiences, the chapter provides a flavour of fighter tactics and the controversies regarding this subject.

Chapter four deals with operational flying, from the perspective of Coastal Command, whose efforts have been overshadowed by the ‘Fighter and Bomber Boys.’ Yet, Coastal Command performed a vital role, particularly in countering U-boats, which contributed towards winning the Battle of the Atlantic. Typically, Coastal Command aircrew encountered awkward conditions, on lengthy, monotonous sorties, and frequently relied on aging or obsolete aircraft.

Ferry pilots, and personnel with Ferry Command, feature in chapter five. Bold plans were formulated to fly bombers manufactured in America across the Atlantic to Britain, no easy task in the 1940s. As the war progressed other ferry routes were established, notably via the South Atlantic and West Africa that proved vital in supporting the North African campaign. Another strand of the chapter, discusses the experiences of aircrew that operated transport aircraft with Ferry (later Transport) Command. Many had already completed one or more tours with Bomber Command. Although ferrying supplies might seem unglamorous, it was an essential activity. Transport aircraft also supported airborne operations, by dropping paratroopers and supplies, or by towing glider borne units into action.

The experiences of ground crew are explored in chapter six. Pilots and aircrew simply couldn’t have operated effectively were it not for these dedicated individuals, who worked long hours to service aircraft. A close bond frequently existed between ground crews and aircrew, as those maintaining aircraft were only too well aware of the stresses and strain suffered by men flying on operations. The chapter also highlights a host of other non-flying related activities performed by men and women. Sometimes derided as ‘chair polishing’ roles, in their own way these contributed towards the overall smooth running of the Service. Duties ranged from administration, such as pay and accounts sections, to the risky and courageous work of bomb disposal squads.

For pilots and aircrew, one of the most frightening prospects was that of being shot down and trapped in a burning aircraft. Chapter seven considers the experience of being shot down, from the perspective of those who endured it, and survived. Many didn’t. When shot down, some airmen were successful in evading capture, and during the war training in escape and evasion techniques improved. Others, as the chapter shows, endured a torrid time behind the wire in POW camps in Nazi occupied Europe. Contrary to the popular image in films and novels, there was nothing glamourous about becoming a POW, albeit opportunities to intimidate guards or mount escapes boosted morale. Conditions for prisoners in the Far East, where the Japanese didn’t recognise the Geneva Convention, were equally as appalling, if not worse. Another theme of the chapter is crashes and accidents. Sadly these were common features of wartime life that killed numerous personnel, frequently having a significant impact on those that witnessed them.

Chapter eight illustrates the challenges facing the RAF during the immediate post-war period, when many regular personnel continued to serve, although they weren’t necessarily involved with operational flying. The demobilisation process, including the liberation and repatriation of POWs, is outlined, plus consideration given to how individuals viewed their war service, and what effects it had on them. Having survived the war, some personnel deeply resented being liable for further reserve service. Likewise, during 1946 a ‘mutiny’ or strike occurred in the Far East, largely because airmen stationed there were frustrated over what appeared to them as lengthy delays in their demobilisation.

NB If you’d like to read more about the experiences of men and women who served with the wartime RAF please look out for:

James Goulty Eyewitness RAF: The Experience of War 1939-1945 (Published by Pen and Sword c. November 2020)

With thanks,

James Goulty

You can preorder a copy here.