Guest Post: Janet Dubé

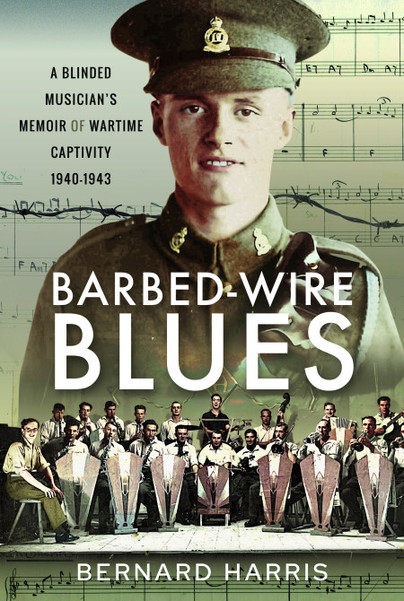

There was a war on 80 years ago when my parents married, and like many couples, they couldn’t live together. My father, Bernard Harris, was an army bandsman on combat training with his regiment, ready to be posted abroad. Over the summer of 1940, they spent time camped out on Newmarket racecourse.

In November the regiment sailed from Liverpool on a requisitioned cruise ship into the Atlantic and around Africa to enter the Mediterranean through the Suez Canal, where they had Christmas dinner. After two months in the north African desert, they crossed the Mediterranean to Greece. They travelled peacefully from south to north, but neither the Greek Army nor its Allied reinforcements could withstand the ensuing Nazi invasion. They were forced to retreat back from north to south under aerial bombardment.

By the time the German Army reached Athens on April 27th many British, Australian and New Zealand servicemen had got away to Crete, or back to Africa. Others, including Bernard’s regiment, were overtaken by the Battle of Corinth. Bernard was bombed, captured, shot and left for dead.

Twenty five years later he began to write his stark fractured memories of that day and the following two and a half years of his life as a wounded Prisoner of War in Greece and Germany. Years later again, I found a typescript in a filing cabinet at his last home, I’m pleased to say that Pen & Sword is now publishing Bernard’s memoir, under the title Barbed-Wire Blues.

Bernard Harris was both an ordinary soldier and a talented, skilled musician: both unlucky and very lucky. When he nearly died at least three times, Bernard’s life was saved by Greeks and Germans as well as Scots and other captured Allies. Though a German captor told him he was blinded, a captured Scots doctor saved one eye. In his Greek hospital pyjamas, playing an accordion like a piano, he joined a regular concert party of prisoners entertaining other prisoners. He inspired and directed bands and weekly concerts in hospital camps in Germany. He was willingly a genuine agony aunt and most unwillingly a leading lady when somebody found a copy of a play by A.A.Milne.

Definitely unfit for further military service, Bernard was among the first wounded PoWs to be repatriated in 1943. He was later awarded the Military Medal and had a successful career as a professional musician.

Barbed-Wire Blues is available to preorder here.

Full book description:

As the author, a young Army bandsman lies wounded at the Battle of Corinth, he is shot between the eyes at point blank range. Miraculously he survives but is blinded. In a makeshift hospital a young Greek volunteer saves his life with slices of boiled egg. Captured Allied medics later restore the sight in one eye.

In this moving and entertaining memoir Bernard describes daily life in POW camps in Greece and Germany. He established a theatrical group and an orchestra who perform to fellow POWs and their German guards. A superb raconteur, as well as a gifted musician, the author’s anecdotes are memorably amusing. Bernard was repatriated via Sweden in late 1943.

While blinded in one eye and seriously wounded, the author was told by his New Zealand doctor, fellow POW and musician John Borrie, ‘When nothing else will do, music will always lift one up’. Barbed Wire Blues’ inspirational, ever optimistic tone will surely have the same effect on its readers.