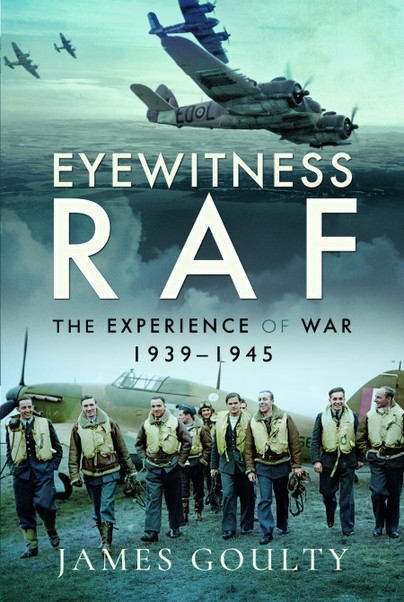

Author Guest Post: James Goulty

Eyewitness RAF: The Experience of War 1939-1945

Before the war RAF strength was 117,890, and on mobilisation in 1939 this was increased by 58,100 with the addition of reservists and auxiliaries, although a substantial number of these lacked training. From this relatively humble beginning, a large wartime force was fashioned that served around the globe. By 1944, when wartime recruiting was halted, around 1.2 million men and women were serving with the RAF, approximately seventy percent of who were employed in non-flying trades. This demonstrates the immense effort that was required to support operational squadrons, and that trained aircrew held an elite status within the RAF, not least because only around five percent of those that applied for aircrew training were successful.

The experiences of aircrew loom large in the book, but hopefully the reader will also come away with an appreciation, that for many, their wartime RAF service wasn’t necessarily concerned with flying. Life at squadron level and below, features heavily and the narrative is based around the personal experiences of a wide variety of men and women. Sources employed range from official documents to oral histories and personal memoirs.

Chapter one focuses on recruitment and training, including what motivated individuals to enlist. Invariably the RAF proved popular, even for those not destined to fly, and simply being associated with aviation in some form held a degree of romance. The chapter outlines what it was like to be inducted into the wartime RAF, and notably describes the role of women serving with the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF). Although they didn’t fly, women performed a multitude of important tasks ranging from intelligence and signals work to maintaining/repairing aircraft. The flying training organisation, which is often overlooked, is also highlighted, using a variety of personal experiences at Elementary Flying Training Schools and Service Flying Training Schools or the equivalent.

Chapter two discusses bombing operations, including examples from the campaigns in North Africa and Burma. Although bombing was a feature of most theatres, central to this chapter are the experiences of personnel engaged in RAF Bomber Command’s prolonged offensive against Nazi Germany, and the increasing technological sophistication that this entailed as the war progressed. Consideration is given to the impressions that aircrew had of their aircraft; the dynamic between the different members of a bomber crew; the components of a typical sortie; the role of Pathfinders in trying to improve the accuracy of bombing; and the sorts of coping mechanisms that personnel employed to deal with the pressure of operations, including the fear of being branded LMF (Lacking in Moral Fibre). As one Lancaster pilot put it, you had to face up to the high casualty rate, ‘and probability of one’s own death… One had to consider oneself already dead. In that way one could live with honour, without fear of cowardice or death.’

Chapter three explores the operational experiences of fighter pilots, and illustrates the characteristics they required, plus the different roles performed by fighter aircraft. It comments on fighter tactics, providing a flavour of the controversies that existed. Graphic descriptions of aerial combat, as seen through the eyes of those that experienced it are included, and noteworthy for demonstrating the shear mental and physical exertion that flying a high performance fighter in combat could entail.

Similarly, chapter four deals with operational flying, this time from the perspective of Coastal Command, sometimes dubbed ‘Kipper Fleet.’ Its efforts have tended to be overshadowed by those of the ‘Fighter and Bomber Boys.’ Yet, Coastal Command was vital in helping the navy to counter U-boats, which contributed towards winning the Battle of the Atlantic. Typically, Coastal Command aircrew encountered awkward conditions, were faced with lengthy, monotonous sorties, and frequently relied on aging or obsolete aircraft. As the chapter shows, other important roles included: protecting and escorting convoys, anti-shipping operations, and Air Sea Rescue work.

Likewise, chapter five concerns flying, but this time from the viewpoint of ferry pilots, and personnel who served with Ferry (later Transport) Command. Bold plans were formulated to fly bombers manufactured in America across the Atlantic to Britain, no easy task in the 1940s, especially in winter. As the war progressed other ferry routes were opened-up, notably via the South Atlantic and West Africa that proved invaluable in supporting the North African campaign. Another strand of the chapter, discusses the experiences of aircrew that operated transport aircraft. Many, including Reggie Wainwright, who features in the book, had already served one or more tours with Bomber Command. Although ferrying supplies might seem unglamorous, it was an essential activity. Wainwright, for example, was awarded the Air Force Medal for his role as navigator in an unarmed, heavily loaded transport aircraft routinely flying between Gibraltar and Malta. Supporting airborne operations, either by dropping paratroopers and supplies, or by towing glider borne units into action, was another important function.

Chapter six concentrates on non-flying activities, notably the experience of ground crew who worked long hours to keep aircraft operational, and usually formed a close bond with the pilots and aircrew they supported. Equally, a range of other non-flying related activities were performed by men and women in the wartime RAF, covering everything from intelligence work and administrative roles to the under-recognised work of bomb disposal squads. Some of these were derided as ‘chair polishing’ roles, but all contributed towards the overall effective running of the Service.

For all aircrew, one of the most frightening prospects was that of being shot down and trapped in a burning aircraft. Chapter seven considers the experience of being shot down, from the perspective of those who endured it, and survived. Many didn’t. When shot down, some airmen were successful in evading capture, and training in escape and evasion techniques improved during the war. Others endured a torrid time behind the wire in POW camps in Nazi occupied Europe. Contrary to the popular image, there was nothing glamourous about becoming a POW, albeit opportunities to intimidate guards or mount escapes helped boost morale. Conditions in the Far East, where the Japanese had no respect for the Geneva Convention, were equally as appalling, if not worse. Another theme of the chapter is crashes and accidents, an all too common feature of wartime life. These not only killed numerous personnel, but also had a significant impact on those that witnessed them.

Chapter eight covers demobilisation and coming home after the war. The demobilisation process, as it affected individuals, is discussed, alongside the liberation and repatriation of POWs. The chapter also gives consideration to how individuals viewed their war service, and what effects it had on them. Additionally, it illustrates the challenges facing the RAF during the immediate post-war period, when many regular personnel continued to serve, although they weren’t necessarily involved with operational flying. For example, Harry Blee who was interviewed for the book, served as a flight engineer on Liberator bombers in the Far East, before obtaining a permanent commission. He went on to hold a number of administrative appointments post-war, retiring as a wing commander in 1975.

It is now over 75 years since the end of the Second World War, and sadly the numbers of surviving RAF veterans are rapidly diminishing. Consequently, it is important that we continue to respect their memory, and appreciate the sacrifices they made in the name of freedom. Hopefully, Eyewitness RAF proves informative and enjoyable, plus acts as a fitting tribute to the many ordinary men and women who served with the wartime RAF.

James Goulty

Eyewitness RAF is available to order here.

Photo credits: Author’s Collection (with assistance from Robert Goulty, Simon Blee and Charlie Wainwright).