Author Guest Post: Nicholas Milton

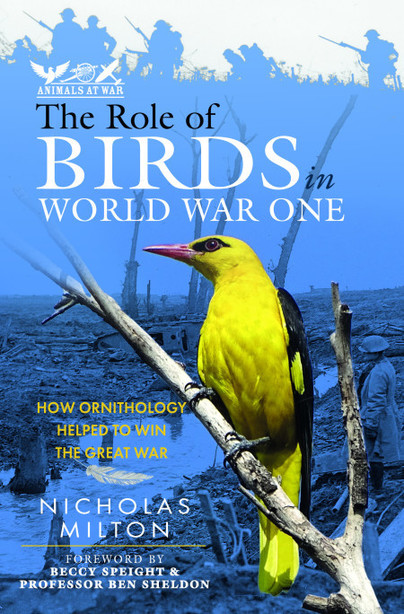

The Role of Birds in World War One: How Ornithology Helped to Win the Great War

Although World War One or ‘The Great War’ ended over a century ago and it has now firmly passed into history, the sheer scale of the sacrifice continues to resonate with us to this day. What is it about World War One that continues to draw us back to it? Perhaps it is the fact that no other conflict so encapsulates the utter futility of war. In the run up to Remembrance Day on 11 November, we commemorate all those who have lost their lives in conflict but the red poppy we all wear with such pride will always be associated with The Great War.

The enduring fascination of the conflict is no better illustrated than the popularity of the recent release from Netflix, ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’. The third adaptation of the classic 1929 novel by Erich Maria Remarque, it is as bleak and brutal a depiction of war as you will ever see on the screen. Yet film makers from Edward Berger, writer-director of All Quiet on the Western Front, to Sam Mendes, who produced the hugely popular movie 1917, continue to miss out one very important part of the conflict – bird song.

Far from being All Quiet on the Western Front in between all the barrages and explosions there was a remarkable amount of bird song from the woods behind the lines to the trenches and across no-man’s land. Birds seemed almost immune to the conflict and carried on regardless singing above the noise of battle. With the war soon descending into stalemate, the soldiers started sending back remarkable bird reports from the field with the letters home to their families. These accounts movingly show how birds helped to bring joy, solace and above all hope to a generation of young men who had everything to live for but who died in their droves on the battlefields of France and Belgium.

The role of birds in maintaining morale at the front was extensively reported in the newspapers, magazines and ornithological journals of the day. The list of birds seen or heard by soldiers serving in all the theatres of war was truly impressive, ranging from the common like sparrows, skylarks and swallows to the exotic like golden orioles, hoopoes and bee-eaters. It also included many enigmatic species like nightingales whose own explosive song often competed with the guns at dawn. Remarkably, one soldier, Christopher James Alexander, who died at the Battle of Passchendaele on 5 October 1917, counted 107 species for the year, his brother in his obituary writing it was ‘a wonderful total under such conditions’.

It is in recognition of their unsung contribution to the conflict that I have written the book ‘The Role of Birds in World War One – How Ornithology Helped to Win the Great War’. Not only does it tell the story of how birds found themselves in the firing line on the battle front but also on the home front. As well as declaring war on Germany on 4 August 1914, the government also declared war on the humble house sparrow, farmers falsely accusing it of destroying Britain’s dwindling wheat and oat supplies. To exterminate them rat and sparrow clubs were formed by the Board of Agriculture and a bounty was put on the tiny head of every house sparrow. Clubs were formed across Britain with schoolboys and clergymen competing to see who could kill the most birds, the slaughter soon extending to all small birds in the countryside.

From the outset, the clubs were opposed by the fledging Royal Society for the Protection of Birds who fought its own battle against the powerful Board of Agriculture, accusing it of ignoring the economic value of birds and encouraging cruelty among children. Slowly winning over the public to its cause by its campaigning work, the Society finally emerged victorious and, in the process, came of age, becoming the powerful voice for conservation we know today. If film makers wanted to tell the story of the Great War from a new angle, they could do no better than write a film about the history of the RSPB.

Nicholas Milton’s latest book, The Role of Birds in World War One: How Ornithology Helped to Win the Great War, is available now.