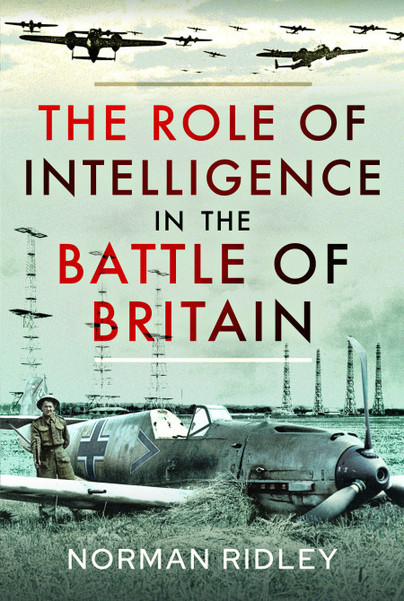

Author Guest Post: Norman Ridley

The Role of Intelligence in the Battle of Britain

The Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz said; ‘War is the realm of uncertainty; three quarters of the factors on which action in war is based are wrapped in a fog of greater or lesser uncertainty’, which is commonly abbreviated to refer to ‘the fog of war.’ His countryman Helmuth von Molkte elaborated on the theme of uncertainty in battle when he said;’ No plan of operations extends with certainty beyond the first encounter with the enemy’s main strength.’ In other words, once forces have engaged in battle, an appreciation of how it is evolving through time is often only arrived at through inspired guesswork, which is not particularly recommended despite its occasional efficacy, or operational intelligence.

In 480BC, the Persian generals were said to have watched the of Battle Salamis from the heights above the isthmus, although it cannot have made for comfortable viewing, and even had they seen disaster coming as the Greek ships stormed into view and decimated the Persian fleet, there was little chance that they could have sent warning and influenced the outcome.

Later, we have the Napoleonic image of generals sitting astride their mounts and viewing the battlefield from higher ground. From here they could send orders to their troops engaged in critical sectors of the battlefield and, to some extent modify tactics according to their observations.

Battlefield intelligence played only a limited tactical role in the First World War as troops bludgeoned each other in brutal, bloody and tragically pointless battles and even the first phases of the Second World War in Poland and France were characterised by lamentable intelligence on the part of the rapidly vanquished defenders.

Come the Battle of Britain, however, British military intelligence was to cast off its mantle of the, often bungling, gentleman spy in the shadows and entered the age of electronic intelligence with its use of radar and communications surveillance. Germany, too, had adopted new technologies in these field and were just as advanced and its radar programme had been adapted primarily for defence, much the same as Britain had done but, crucially, they were the attacking force during the Summer of 1940 and in that role, their radar was redundant. Britain, however, was to accrue huge benefit from their radar surveillance and quickly dovetailed it seamlessly into an integrated system of fighter control which became known as the ‘Dowding System’.

By the end of August, however, the Luftwaffe had begun to inflict damaging blows to the beating heart of the British defensive network at Biggin Hill and RAF Fighter Command was faced with having to contemplate the abandonment of its south coast airfields leaving open the German bomber flightpath to London.

Luftwaffe intelligence, in stark contrast to the British effort, was limited to strategic analyses based, to a large extent, on supposition and wishful thinking. Wiser voices that offered sounder judgements were given short shrift. Reports from General Martini’s radio intercept service about the function of ‘radio towers’ all along the British coastline, were monitored and filtered by Intelligence chief ‘Beppo’ Schmid to avoid contradicting his own assessments and those of Göring who dismissed them as targets of limited importance. Operational commanders such as the bomber commander of Luftflotte 3, Hugo Sperlle, whose aircraft were feeling the full force of RAF defences, knew that Schmid’s assessment of Fighter Command aircraft numbers rapidly dwindling could not be true but he, like many of the fighter leaders were accused of negativity and defeatism.

The truth was that the Luftwaffe had arrived at a moment in early September where it was on the cusp of making a crucial breakthrough in the battle but failed to appreciate it. Had the bombers continued to pound the control center’s such as Gravesend which had taken over all control responsibilities from Biggin Hill, the Battle of Britain narrative would certainly have had a different outcome although discussion of what that might have been is outside the remit of the book.

When Göring ordered Sperlle and Albert Kesselring, commander of Luftflotte 2, to concentrate their attention on London itself and away from the airfields, it gave Fighter Command an immeasurably important opportunity to take a breath, re-group and patch up its fractured defensive network. It might truly be said of Göring that in this moment he plucked, if not exactly defeat then, failure out of the jaws of success.

You can preorder a copy of The Role of Intelligence in the Battle of Britain here.