Author Guest Post: Paul Johstono

THE PTOLEMAIC ARMY AND THE BATTLE OF BABYLON

In December 246 BC, 2,265 years ago this month, the larger part of the army of Ptolemaic Egypt and its king, Ptolemy III, could be found far, far from home, not far from modern Baghdad. It was the middle of the Third Syrian War. The Ptolemaic army was deep in Seleucid territory, pressing to extend early advantages with military conquests that took them city-by-city, and even street-by-street, through the great cities of Mesopotamia.

BACKGROUND: THE LAODIKEAN WAR

The war began when Laodice, the former queen of Antiochus II Theos, poisoned her husband, set her eldest son Seleucus II on the throne, and ordered an assassination attempt against Antiochus’ current queen Berenice and Berenice’s infant son. Berenice, however, not only survived the first attempt, but was also able to send a plea for help to her brother in Egypt, king Ptolemy.

Many in Syria sympathized with the young queen, and she secured herself in the royal palace at Daphne, in the hills above Antioch, surrounded by her attendants and a bodyguard of Galatians. When Berenice’s plight reached Ptolemy III, he mobilized his forces and sailed for Syria. His fleet advanced rapidly, but by the time he arrived Berenice had been killed in another assassination attempt. But because her opponents were unsure she was dead, Ptolemy was able to capitalize on the confusion and general disgust with Laodice to claim a sort of authority in Antioch as defender and avenger of his sister and nephew.

Ptolemy III’s rapid advance won three of the four most important cities in Syria, including the capital of the whole empire, with hardly a blow. But Laodice and Seleucus II were still in command in Asia Minor, and many of the cities and satrapies to the east of Antioch seemed to favor Seleucus over the Egyptian newcomer. By mid-autumn the Ptolemaic field army, including the elephant corps and the Macedonian phalanx, joined Ptolemy. With them he commenced a campaign of conquest in Asia.

THE PTOLEMAIC ARMY IN MESOPOTAMIA

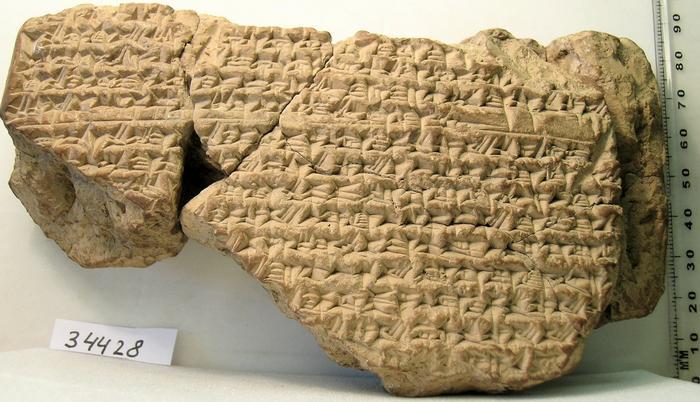

In December (in the Babylonian month Kislîmu, from 26 November-25 December) the Ptolemaic army arrived at Seleucia-Sippar, a Hellenistic refoundation of an ancient Sumerian city. Sippar was on the east bank of the Euphrates, on a canal that connected it and the Tigris. From Sippar it was under 16 miles to Seleucia on the Tigris, the second city of the Seleucid empire, and less than 40 miles to great Babylon astride the Euphrates. What we know of this campaign comes from a Babylonian chronicle in cuneiform, which readers may consult here.

The Ptolemaic army attacked Sippar, and the Babylonian chronicle records that the commander at Babylon, who had a large division of the Seleucid army at his disposal, chose not to risk marching to the relief of Sippar. Instead, he “shut in the royal army that was in Babylon before Ptolemy,” barred the gates, and waited for the Ptolemaic army to make the next move.

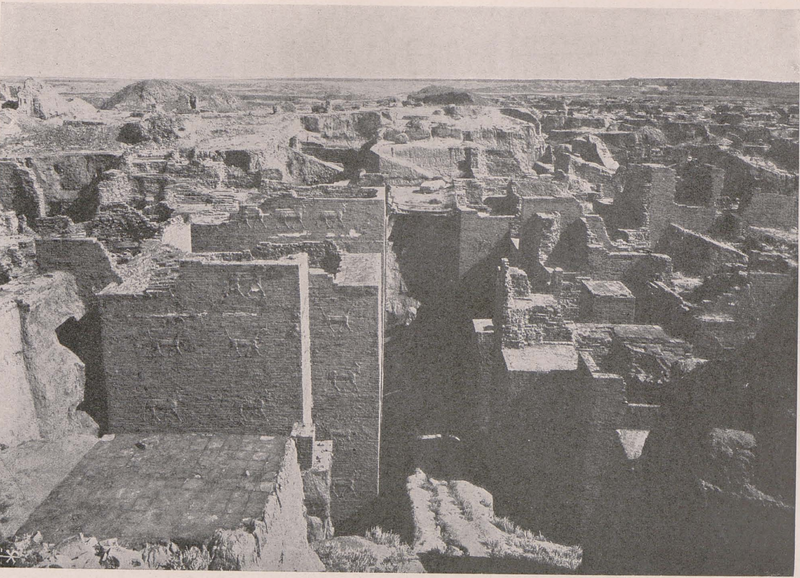

On the 9th of January, the 15th of the Babylonian month Tebêtu, a division of the Ptolemaic army arrived outside Babylon with siege machines transferred from Seleucia-Sippar. The relocation of siege engines suggests the smaller city had mostly fallen. Barges probably bore the engines down the Euphrates to Babylon. King Ptolemy, however, stayed at Sippar. The Ptolemaic troops invested the city for four days, then on the 13th of January assaulted the city and captured the Bēlet-Ninua citadel. The temple of Bēlet-Ninua, the Lady of Nineveh (Ishtar), was near the course of the northern city wall on the western side of the Euphrates. Its status as a citadel suggests the temple or adjacent buildings had been developed into a fortification to anchor defenses in west Babylon. When Ptolemaic troops crossed the wall the defenders in the citadel fled for the east bank, and the Ptolemaic army poured into the city. The chronicle calls the Ptolemaic troops “Hanaeans,” an old Babylonian word for barbarians, also used for the Macedonians of Alexander nearly one hundred years earlier. It accuses the ironclad Hanaeans of slaughtering both soldiers and civilians. The 13th and following days in January 245 BC may have seen the sacking of west Babylon.

On the 18th of January yet another division of Ptolemaic troops arrived at Babylon from Seleucia-Sippar, this time under command of an “illustrious prince.” The chronicle asserts he had marched much of the army up from Egypt. This probably references the Ptolemaic settler army, which would not have accompanied Ptolemy III to Syria by sea. The commander is often recognized as the Xanthippos whom Ptolemy III later left in command of Mesopotamia. The remainder of this piece assumes he was Xanthippos. On the 20th of January Xanthippos entered the great Esagila temple and offer sacrifices. The Esagila, the most important of Babylon’s temples, lay on the east bank. This suggests Xanthippos and his reinforcements captured it in a fresh assault launched between the 18th and 20th.

From the Esagila the conquest of the city turned to bloody urban combat. The Seleucid defenders held the citadel complex around the famed Ishtar Gate on the north wall of the city. Xanthippos fortified the Esagila, half a mile away. In between lay the ruined stepped pyramid Etemenanki (the tower of Babel) and numerous temple complexes. These became the mud-brick battle ground for numerous engagements, sieges within a siege. Over the next week or two the Ptolemaic attackers won a string of victories that brought them ever closer to the citadel itself. The commander at Babylon holed up in the palace (the chronicler’s disdain for his cowardice is thinly masked) but the Seleucid troops in the city “were slaughtered” as their positions fell.

As their defeat drew near, the beleaguered defenders of Babylon gained a breath of hope when a relief column reached the city. They came from Seleucia on the Tigris, the second city of Seleucid Asia. The relief force entered Babylon, probably through the northeastern Marduk Gate, on either 29 January or 8 February (the 6th or 16th of the Babylonian month Shabatu). Xanthippos was ready. The Ptolemaic forces trounced the relief force resoundingly. Even worse, while they were marching to Babylon the Ptolemaic army at Sippar (king Ptolemy’s division) counter-attacked Seleucia on the Tigris and defeated the garrison left behind.

The assault on the citadel continued into February at least, and the chronicle breaks off before the siege resolved. The Ptolemaic successes were not without cost. Papyri discovered in Egypt testify to Ptolemaic soldiers who died in the Third Syrian War. Some of them, like the infantrymen Kallikles and Lysanias (Petrie Papyri III, 105), may have fallen in the street battles of Babylon, among the fearsome ironclad Hanaeans who brought Babylon to its knees in January 245.

Learn more in The Army of Ptolemaic Egypt 323 to 204 BC which is available to order here.