Author Guest Post: Philip Hamlyn Williams

Imagine the scene, rather like General Horrocks addressing the officers of 30 Corps in the film A Bridge Too Far. Instead of Horrocks, the key note speaker is spritely Brigadier Jim Denniston, former Seaforth Highlander, and, as Director of Ordnance Services for the 21st Army Group, he is addressing officers of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps as they make final preparations for D Day. They are approaching the culmination of four hard years of preparation, or perhaps forty years since many of them had served through the Great War. Some had been at the sharp end in the British Expeditionary Force which withdrew to Dunkirk. When I first read of this scene, I needed to discover where these men had come from; what had prepared them for this moment. The result of my research is my book, Dunkirk to D Day.

I look at their background and childhood, the world of work before 1914, their service during the Great War and what they did in the interwar years. The first years of the Second World War were for these men a time for learning from mistakes, some painful but all aimed at D Day. Until VE Day, activity continued at a high level and, even in the latter part of 1945 and into 1946, there was the army of occupation to supply. Although I refer here to men, the work of women was equally crucial, not least the members of the ATS who served in all the depots. I might also add my mother, Betty Perks, who was then my father’s PA.

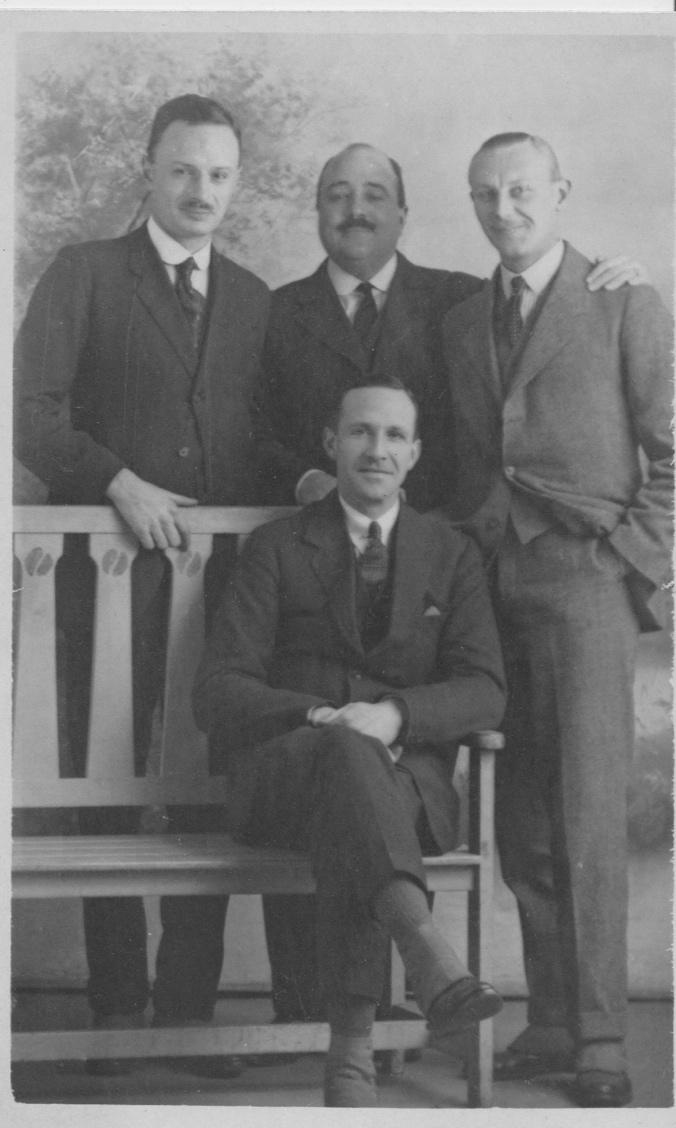

Among the speakers, addressing the group of some forty men gathered in the Debating Hall of the Royal Empire Society, was my father Major General Bill Williams Controller of Ordnance Services and Director of Warlike Stores. The buck would stop with him should the supply services fail. Alongside him was another Major General, his friend and rival Dickie Richards, whose memory of France in 1940 would have been vivid. He had commanded the ordnance depot in Le Havre. He had gone on to command Ordnance Services in the Middle East before returning to the War Office to take charge of the supply of Clothing and Stores.

In the audience were three other BEF veterans, Brigadiers de Wolff, Palmer and Cansdale. de Wolff had crossed to France in September 1939, but had been recalled in November to manage the project he had conceived to relocate the massive arsenal from Woolwich to deepest Shropshire away from the danger of enemy bombers. Palmer had commanded the ordnance depot at Nantes and may have been amongst the survivors of the Lancastria which sank whilst evacuating troops after Dunkirk; Palmer would go on to command the depot at Bicester specifically built with D Day in mind. Cansdale was Bill William’s deputy with particular responsibility for field activity. All three had been with Bill and Dickie on the first Ordnance Officers course (the Class of ’22) held after the Great War through which all five had served.

Another veteran of the Great War and Class of ’22 was Alfred Goldstein who, at the time of Dunkirk, was commanding the ordnance contingent in the Malta garrison and then throughout the siege; at the time of D Day he commanded the armaments depot at Greenford which was first port of call for equipment en route to Normandy. Alfred had passed out top of the ordnance officers course, with Bill Williams a close second.

Aside from these regular soldiers were men from industry who held temporary commissions. Listening to Denniston was Colonel Bob Hiam, a Dunlop director, who had commanded the armaments depot at Old Dalby in Leicestershire and who would command the Advance Ordnance Depots to be set up outside Caen and at Antwerp. Another Dunlop man, Colonel Robbie Robinson, was not present having been appointed Ordnance Inspector Overseas; he had set up the Motor Transport Depot in Sincil Lane, Derby and had then recommissioned the depot at Feltham with more than an eye on the coming war in the Far East. Feltham was, at the time of D Day, commanded by former Tecalemit director Arthur Sewell. The Army Centre for Mechanisation was at Chilwell near Nottingham and its chief ordnance officer, English Steel director Reddy Readman, was in the audience. He had overseen the massive packing operation for D Day which had seen some three hundred million items packed and labelled in depots and by volunteers: Women’s Institutes, off-duty fireman and school children.

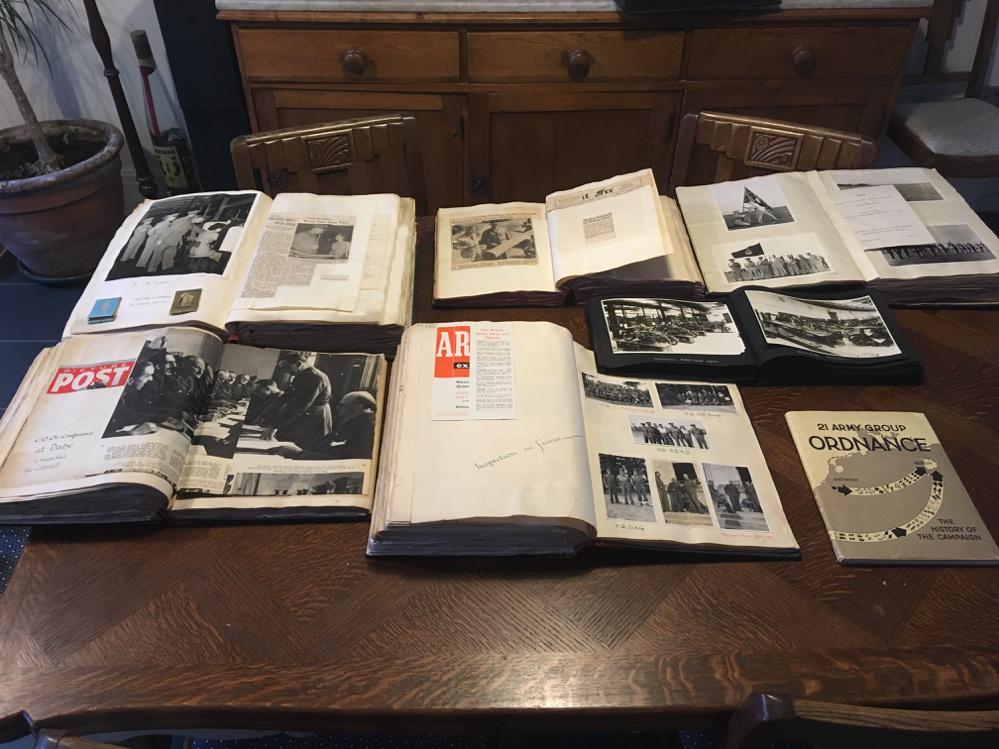

The late forties, for some, meant the civilian world of work; an economy desperate for exports; for others it was a well-earned retirement. Many died before their time, exhausted by the task that had fallen to them. Dunkirk to D Day begins in the world of the pony and trap and ends with a Britain that ‘never had it so good’. In between there are adventures overseas, inventive and far seeing management initiatives at home, many recorded in albums and diaries by Betty Perks to whom I owe a huge debt of thanks.

……………………………………………………………………………

Dunkirk to D-Day is available to preorder here.

You can follow Philip on Twitter and his blog.