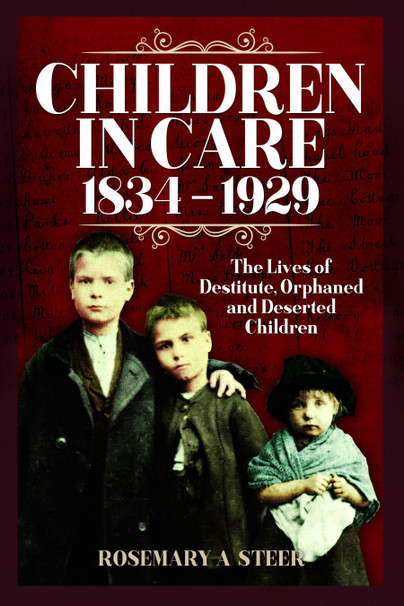

Author Guest Post: Rosemary A Steer

Children’s Charities

Many charities providing support and services for children and young people today, such as Barnardo’s, Coram (formerly the Foundling Hospital), the Children’s Society (formerly the Waifs and Strays Society) and Fegans, have their origins 150 years or more ago, founded in response to the plight of destitute, orphaned and deserted children who struggled to find the basic necessities of life – food, shelter and clothing. Some children were living on the streets of our big towns and cities, others just about surviving in overcrowded, dirty and cold dwellings with poor sanitation, little or no furniture and not enough food. The best the state could offer most of these children in the nineteenth century was a place in a workhouse, a harsh and grim place for adults, never mind children, or in a poor law residential school which might house over a thousand pauper children, where the children could quickly become institutionalised and where disease was rife.

From the 1860s though, various acts of parliament allowed poor law unions to contract out the care of some, at least, of their pauper children to the voluntary societies, taking them out of the large poor law institutions, often into country villages beyond the union’s boundaries. The charities also took children into care directly, either through local referrals or, like Thomas Barnardo, by scouring the streets of London to find children in need of his help. Many charities offered pioneering services such as fostering or small residential cottage homes, with more focus on the child’s needs and on family life, even if that ‘family’ comprised 20 or 30 children and their carers in a residential home. Some provided specialised industrial or agricultural training homes, such as the Waifs and Strays Society’s St Chad’s home near Leeds, which taught machine knitting or Fegan’s farm school at Goudhurst in Kent, which prepared boys for emigration to Canada. Children in foster homes and small cottage homes were often able to attend the local school and mix with other children, unlike the workhouse children who were usually taught within the institution.

Today, as 150 years ago, these charities work to support young people directly and indirectly in many ways, often in partnership with other organisations, raising awareness and responding to current issues, such as mental health, child exploitation by criminal gangs, young carers and those who run away from home. Poverty and destitution are still key issues for children and young people today though, especially with the cost of the basic necessities of life, such as food and energy supplies, rising so rapidly. And these charities will continue to be there for children and young people who need them.

Many children’s charities, including those that have long-since gone, were founded through the vision and philanthropy of one person such as Edward Rudolf, Thomas Coram, Annie Macpherson or Thomas Bowman Stephenson. Here are a few stories from the past to show the impact one of the charities, the Children’s Society, then the Waifs and Strays Society, had in its early days, a century or more ago.

Mrs Brandreth’s Charity for Workhouse, Orphaned and Destitute Children (The Children’s Society)

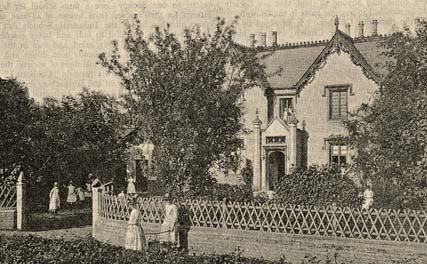

About 1875, Mrs Louis Brandreth, wife of the Rector of Dickleburgh in Norfolk, started a children’s charity in the village, prompted by the plight of three local children ‘whose father was dead and their mother gone away’ who would otherwise have had to go into the workhouse. By the time the charity was taken over by the Waifs and Strays Society thirteen years later, Louisa Brandreth was managing two children’s homes for girls in the village, organising fundraising and interacting with the poor law unions, arranging fostering placements for boys and girls and even some private adoptions, as well as finding work for the children when they left care. Even after she moved to Wanstead in Essex, after the death of her husband, Mrs Brandreth continued to look after her ‘old girls and boys’, organising annual get-togethers for the girls in service in London. By the time the Dickleburgh homes closed, and the Waifs and Strays Society ceased to operate in the village, over three hundred children had been in care in Dickleburgh over a period of 35 years.

Rosa Garnham

The ‘old girls’ of the Dickleburgh homes were remembered at Christmas time, with a present for each on the Christmas Tree, packed and ready for posting; in 1897, eighty presents were sent out. Former residents were also welcomed back to the homes for holidays or rest. In February 1889, Rosa Garnham, who was in care in Dickleburgh for about six years during the 1880s, wrote in the Waifs and Strays magazine:

When we go out to service we are not discarded, but come back for our holidays. O, what happy times we have spent in the dear old Home! for which I feel very grateful to my kind friend Mrs B, and all ladies who have taken an interest in our Homes; and I shall always try to do my best, because it is my duty, and also to please my kind friend.

Isola Emms

Perhaps the most remarkable example of the love, care and support given to a child in care in Dickleburgh by the Brandreths and the Waifs and Strays Society is that of Isola Emms who was admitted to the Society and into care in Dickleburgh at the age of sixteen. Isola had physical and learning disabilities and had been physically assaulted by her stepmother. Over a period of forty-five years, Louisa Brandreth and her daughter Rosalind, assisted by the Society, ensured that Isola always had a secure home, either in a residential home or hospital or in what we would now call a ‘supported placement’, with kind people, where she was able to carry out some domestic duties, sometimes for a small wage. At times, the Brandreths took her into their own home when there was no suitable alternative. They ensured that her medical needs were met and managed her funds (mostly from an annual donation from the Mann family of Thelveton) paying all her expenses, including occasional holidays, and then banking the surplus for her. As Rosalind explained in note on Isola’s case file held the Children’s Society Archive:

She is also very sensitive and it would be a terrible thing for her if she ever had to go into any big Institution where she would be one of a crowd…. It has, however, always been most difficult to find suitable places for Isola. She has never been able to learn to read, or write, or tell the time, and is quite incapable of protecting herself in any way from unkind treatment, and would unreservedly trust anyone who was kind to her. She would therefore be at anyone’s mercy and should she be dismissed she would be absolutely powerless to make any arrangement for herself.

Samuel Adams

Sam Adams was one of six siblings who came from the Burton on Trent workhouse into care in Dickleburgh. Sam, the only boy, was fostered with the Vyse family who farmed in the village, while his sisters were resident in the children’s home, Rose Cottage. When Sam was about thirteen and ready to leave school, there was some debate between the Brandreths and Mr Rudolf of the Waifs and Strays Society as to his future, recorded in his case file. According to Mrs Brandreth, he was ‘a sharp and willing boy [but] he [had] a bad hesitation in speech when flurried.’ She suggested as he had learned a little farm work while with his foster parents, perhaps he could be sent to one of the Society’s farm schools to learn farming. Arrangements were in hand for this, but the Revd Henry Brandreth intervened with further concerns about Sam: ‘The difficulty is that the boy who is not very big or strong has a most distressing stammer and if started as a new boy among a party of 30 big & rougher boys it will really be most trying and difficult for him. More than he ought to bear.’ It was eventually agreed that Sam would remain with the Vyse family at a reduced cost, and they would teach him farm work. Three years later, Sam was still living with his foster parents, described as a worker and ‘Boy on farm’, so presumably had bed and board and earned a small wage.

Rosemary Steer

5 December 2022

Children in Care, 1834-1929 is available here.