Author Guest Post: Sir Nick Young

Yes, but what do you actually do?

by Sir Nick Young, former CEO of the British Red Cross.

The question that popped up again and again when I was chief executive of the British Red Cross was a simple one: ‘Yes, but what do you actually do?’

The question was simple but surprising because, to me at least, the answer seemed so obvious, and I used to wonder, slightly indignantly, if my counterparts in commercial companies, or in the public sector, were ever faced with similar queries. And yet, it’s relatively easy to understand why the question needed to be asked.

For many people, the way charities actually work is a bit of a mystery, with their boards of trustees, and senior management teams, and volunteers and paid staff, and opaque messaging about running costs, and sometimes exaggerated claims about need and reach and impact. As charities have become, over the last forty years or so, more professionally run, images of Victorian-style philanthropy and ‘do-gooding’ have begun to dissipate – and yet they linger on and cause confusion in the minds of those who have little experience of ‘charity’ beyond an ad on the TV, an encounter with a collector on the street, a spot of local volunteering, or as a recipient of charitable services.

The Red Cross itself, once described as the UK’s ‘best known but least understood’ charity, is a strange mix of domestic and international activity, of homespun local volunteering and the global politics of conflict and disaster, of free-wheeling humanitarian impulses and careful government-focused diplomacy. It is an organisation with an extraordinarily powerful reputation and brand but often without (except in times of relatively rare conflict and disaster) a regular or constant high-profile presence on the ground, or in the minds or experience of the general public.

Furthermore, the image often associated with the chief executive of major charities is very different to that of their commercial brothers and sisters – more administrator than ‘high-powered executive’, more team player than ‘colourful individual’, more about ‘softy softy’ care than hard-edged profit.

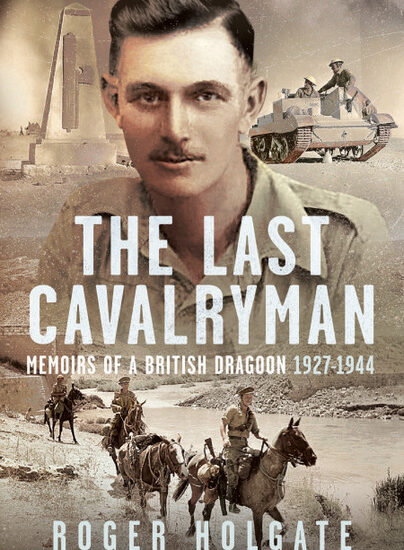

So, part of my reason for writing My Years with the British Red Cross, a Chief Executive Reflects (Pen & Sword 2022) was to answer the simple question ‘what did you actually do?’

But if the question was simple the answer, as I have discovered, is anything but.

The job is multi-faceted and there are as many types of chief executive as there are people filling it, and as many ways of tackling the task as there are chief executives. What can work well in one organisation, for one workforce, can be a disaster for another; and what works at one time, for one set of challenges, can be completely wrong five years later.

It is hard to capture the essence of the job in a few simple words or phrases, and my book does not attempt to do so. Instead, I have tried to describe some of the hundreds of issues and events that I had to deal with during my thirteen years in the role at the Red Cross, and to show how I responded and why.

What was my contribution as chief executive? Well, I used to joke that what I did mostly was make a lot of noise and wave my arms about. And looking back, I can see a lot of truth in that. I had qualified and worked as a lawyer, but I wasn’t an ‘expert’ or specialist in running charities, and I relied a great deal on members of my team to deploy the skills they had in such abundance with what (I hope) was relatively little distracting interference from me.

I felt that my main task was to enthuse, to encourage, to praise and appreciate, in an organisation that was sometimes pretty hard on itself in its drive to live up to the ‘Red Cross ideal’; doing work that, for all our efforts, sometimes seemed barely to scratch the surface of need; and in an environment that was increasingly critical of charities and demanding (rightly) of rigorous accountability.

Of course, I had to master early on all the techniques of strategic planning, budget preparation and monitoring, good volunteer and staff relations and management, organisational design, and so on. But I do see leadership itself as an intensely personal thing that you have to feel your way into – slowly, cautiously, humbly, and with some trepidation – testing the ground as you move forward, but being ever prepared to seize opportunities, as they arise, to make your mark. Passion and compassion, the ability to communicate a powerful vision, emotional intelligence, trust and confidence are all part of the mix.

I loved my job. Every day, every hour of every day, was different. Sometimes it was difficult, hard, scary even. More often, it was exhilarating, inspiring and incredibly deeply moving. I worked with so many able, committed and energetic colleagues and friends, volunteers and staff alike; and met so many people, often in the direst distress or at the worst time of their lives, whose courage and determination to survive and succeed was little short of miraculous. I was privileged to have the chance to serve with them and for them, and lucky to have been given the opportunity to make, sometimes, a difference in their lives.

My Years with the British Red Cross is available to order here.