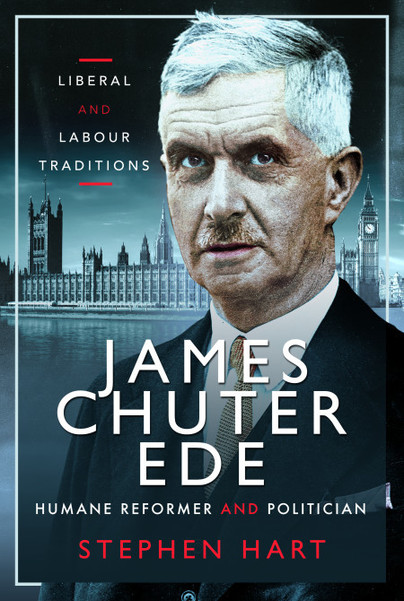

Author Guest Post: Stephen Hart

As we see the Government considering how to pull out of a national crisis, it is interesting to review how politicians have reacted in the past.

When James Chuter Ede became Home Secretary in 1945, it was not the job he expected. He had spent the war years at the Board of Education, had become shadow education minister when Labour left Churchill’s coalition, and thought to continue in that role when Churchill was reelected. If Labour (improbably) won, Ede assumed he would join Clement Attlee’s Cabinet as Minister of Education.

In the event, Attlee gained a landslide and, in choosing his Cabinet that August, decided ‘Chuter Ede was eminently fitted to be Minister of Education, but a Home Secretary is a particularly difficult job and he was far the best man for that. He had therefore to leave Education, which was his special thing, and go to the Home Office.’

What a fine choice it was. Attlee told Ede at the time it would be difficult, and so it proved, though perhaps not in ways either expected.

Ede was called upon to put a programme together speedily to get post-war reforms moving. He drafted Bills on Supplies and Services, on Emergency Laws, and on the Police, which proved the main occupation for Parliament in the early months.

His purpose was to extend the Government’s emergency powers, so rationing in particular could continue. Ede’s political argument was that Government powers would run out in February 1946 if fast action was not taken, while his economic one was that many goods would continue in short supply, and that inflation must be avoided. Speaking to the Commons, he covered rationing of clothing, furniture, fuel, building materials, agriculture and food, and price controls generally. There would be no additional controls, except on prices, and there would be parliamentary supervision over any Regulations, but a five year period was needed, bearing in mind the difficulties to be faced, not least in his own constituency in South Shields, and to avoid repeating the economic problems which followed the Great War.

This was not an easy time to be responsible within government for law and order. Large numbers of young men were returning from the disciplined ranks of the services to their old haunts, released from the restraints of the previous years, and wanting to make the most of their freedom. While withdrawing wartime Defence Regulations was a self-evidently positive step, the changes did cause problems for the Home Secretary.

In December 1945 Ede had to answer a series of questions about the activities of Oswald Mosley and his supporters. Mosley had been released from house arrest, and the Fascists held a meeting in a Bloomsbury hotel, where it was reported a journalist had been manhandled, and several MPs wanted to know what action the Home Office would take. Ede pointed out it was no business of the Government or police to maintain order at private gatherings, though the police would act if a breach of the peace occurred. He did not want to get involved in issuing new regulations, which would be hard to draft, and would run counter to the ideals of a free country. However, he was giving his mind to ‘the control of truculent, armed minorities in a democracy’.

Then there was a ‘crime wave’, or such was its description in various newspapers, with stories of very serious offences, alongside more amusing ones. More guns were in circulation and, in Glasgow, a man had shot dead a woman railway clerk, and injured a porter and a boy at a station, apparently in an unsuccessful robbery. In Surrey, the police had chased a car containing a stolen safe along the Kingston Bypass and into central London, where it smashed into a tram and another car. The safe was recovered, the five men in the car escaped, one of them having thrown a bottle of gin at a motorcycle policeman – but missing.

In Marylebone, burglars gathered up furs worth £300, but then stopped to cut out pictures of pin-up girls from a magazine, and had to leave in a hurry, so overlooking much jewellery and a potential haul of £1,500. In Westmorland, hundreds of pounds’ worth of Christmas turkeys had disappeared. The Daily Mail declared the crime wave was caused by the black market, originating in shortages – turkeys were fetching £10 each. Ede’s measures in response included unannounced closing of specific areas, with roadblocks after 11.30 pm, so motorists and pedestrians would have to satisfy police of their identity and business.

The police were considerably stretched, but in some places a rudimentary neighbourhood watch was formed, using former members of the Home Guard and civil defence. By 1948, Ede had piloted a Civil Defence Act through Parliament. This remained in force until it was replaced in 2004 by the Civil Contingencies Act, which gives the current Government authority to enforce extraordinary powers in the present crisis.

In February 1946, Ede recorded a broadcast appealing for the surrender of firearms, which was circulated through the cinemas. Following pictures of small arms, rifles and much larger ordnance being loaded on to lorries for disposal, Ede was introduced, to give a message about half a minute long. This had been recorded in a BBC studio, before a large microphone and a movie photographer. The film shows his discomfort at this type of speech, betraying the novelty of this use of the media for him. Clearly, new methods were felt necessary to meet the increase in lawlessness following the end of the War. The campaign did get coverage; he kept a cutting from 21 February, which reduced it to doggerel:

‘Slogan for the police fire-arms campaign:-

Chuter wants your shooter,

Take heed, hand it to Ede!’

One of the next problems to address was the outbreak of squatting in the summer of 1946. As there had been no housebuilding during the War, and considerable loss of property because of bomb damage, there was already a shortage of accommodation for those working and living in the towns, particularly in the south of England. To those people were then added some 3½ million servicemen and prisoners-of-war returning home, more children at the start of the baby boom, and more than 100,000 Polish soldiers refusing to return to their own country.

People were sleeping on landings and in kitchens, or were doubling up in poor accommodation. Many men, though earning good wages, were unable to find any homes to buy or rent for their families. The Government had been elected to pursue a policy of considerable housebuilding, but the construction workforce had been dispersed, and the minister responsible, Aneurin Bevan, was concerned about the quality of houses which might be built if the job was rushed. Perhaps Bevan, believing ‘only the best is good enough for the working class’, failed to grasp the urgency, making quality his priority over speed.

So in August 1946 people started squatting in abandoned military camps. This was not generally considered threatening, even if it may have been unlawful in principle; the sites were not in use for other purposes, they were of low value, and it would have been unjust to penalise War heroes for actions driven by extreme circumstances. On 20 September Ede reported that 1,073 camps were occupied by roughly 40,700 people. Some squats were planned as a group, but many were not, and cinema newsreels gave them publicity which spread the concept around. The response of cinema audiences indicated they had much popular support. Next, however, squatters moved into luxury apartment blocks in London, a move planned by the Communist Party.

The Government was torn between sympathy for the plight of the homeless ex-servicemen, and the need to ensure the rule of law. It called upon the Home Secretary, James Chuter Ede, who saw his duty as being to balance civil rights with law and order to chair a Cabinet committee to deal with the crisis. The Government announced that those in army camps could stay until Christmas, and made payments to local authorities to help improve the homes, but took police action against some of the squatters in flats and houses. They decided to withhold water, gas and electricity from houses, flats and local authority property seized, but looked at possibilities for alternative accommodation. They decided to build prefabs, despite Bevan’s misgivings.

When The Observer published a profile of Ede, it stated that the

‘outbreak of civil disobedience took the Government completely by surprise. Its handling obviously required political tact, as well as firmness … agility and acumen at Question Time’.

After summarising Ede’s experience and personality, it concluded he

‘will survive the Squatters’ Revolt and may well advance his reputation by showing that he cannot be hurried into hasty repressive measure or outwitted by astute agitation. He may well achieve more enduring fame by reforming our antiquated prison system … he has a reasonable chance of winning the country’s gratitude for the way he handles both the popular and the unpopular tasks of his high office.’

So it would turn out, though there was considerable work to be done.

Preorder a copy here.