Author Spotlight: Mickey Mayhew

Reinventing Rasputin and his Russian Queen

Historically speaking, both Mary Queen of Scots and Anne Boleyn are now having a pretty good time of it; initially lambasted, both are now literally laden down with those willing to decry the more scurrilous rumours about them. I count myself amongst that reforming rabble, having penned several books about Mary, with one on Anne on the way. But when it came to another historically hounded monarch – Russia’s last tsarina/empress/queen Alexandra – there seemed to be no reforming movement in motion whatsoever. So, I decided to do it myself.

‘Hysterical’; ‘Neurotic’ ‘Meddlesome’ – just some of the less charming sobriquets used to describe the favourite granddaughter of Queen Victoria, who married the handsome Nicholas II in 1894. Their story was tragedy personified; patriarchy demanded a male heir, and when he was born, he developed Queen Victoria’s ‘curse’: haemophilia. Determined to preserve the line, Alexandra eventually turned to the one man capable of curing the boy’s agonising attacks (not only external bleeding, but bleeding into the joints, swelling against the nerves). That man was the Siberian holy man and healer, Grigory Rasputin.

The reason for Rasputin’s visits to heal Alexandra’s son were a matter of state secret. But people gossip; in fact, they can’t get enough of it. Pretty soon, in the Russian psyche, Alexandra and Rasputin were recast as a pair of insatiable libertines, with Nicholas reduced to the unenviable status of a cuckold. But it was all complete – if you’ll pardon my French – crap. But because Rasputin was something of a womaniser and someone who liked a tipple – who doesn’t?! – the damage to the prestige of the Romanovs was irretrievably tarnished. Lies upon lie proliferated; for one, that Alexandra financed Rasputin with a lavish stipend. Really, she didn’t; I’ve been to his apartment in St Petersburg and it is no palace, by any stretch of the imagination. At best, she sewed shirts for him and made little gifts of various religious icons; both were intensely devout, as was Nicholas.

When the First World War erupted, Nicholas was eventually persuaded to take command of the Russian army. In his stead, Alexandra became de facto ruler of Russia, with Rasputin at her side. There is little point in denying that the government operated pretty much a revolving door policy under their leadership, but the snotty insinuation that a ‘mere’ woman – and a devoutly religious one, at that – and a smelly peasant had no right to be running Russia drips through countless books upon the subject. Except mine (but naturally I’m biased). And my book is the first to explore Alexandra’s relationship with Rasputin; previous works are always for the one or the other, but I felt it was time to get some sort of sympathetic movement behind her in the way that people have coalesced their compassion behind Anne Boleyn and Mary Queen of Scots. I sincerely hope that I’ve done both her and Rasputin the justice they deserve.

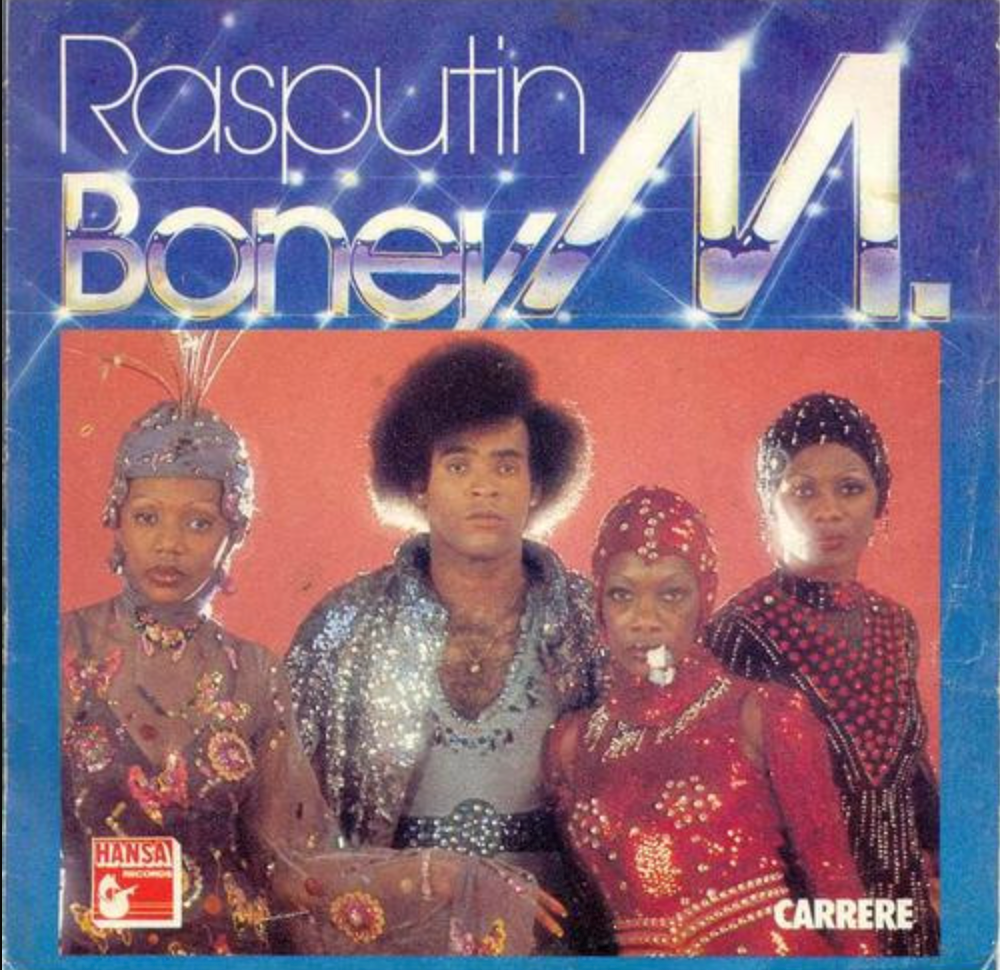

And to think, for so many people, it always starts with that song…

Shop Mickey Mayhew titles here.