Bader’s Big Wing Controversy – Duxford 1940

Guest post from author Dilip Sarkar MBE.

Group Captain Sir Douglas Bader was made a household name in during the Second World War and furthermore in 1956, upon publication of Paul Brickhill’s globally best-selling but romanticised Bader biography, Reach for the Sky, and Daniel Angel’s film of the same name which hit the silver screen a year later. The swashbuckling, legless, Bader arguably remains the most famous RAF pilot of the war. Indeed, the world over he is held in a very special esteem and affection by the public, an inspiration and example on many levels – not least to the amputee community. Nonetheless, the strong-willed Bader was also a ‘marmite’ character, known to be abrasive and over-bearing on occasion, and during the Battle of Britain was actually the cause of a lot of trouble…

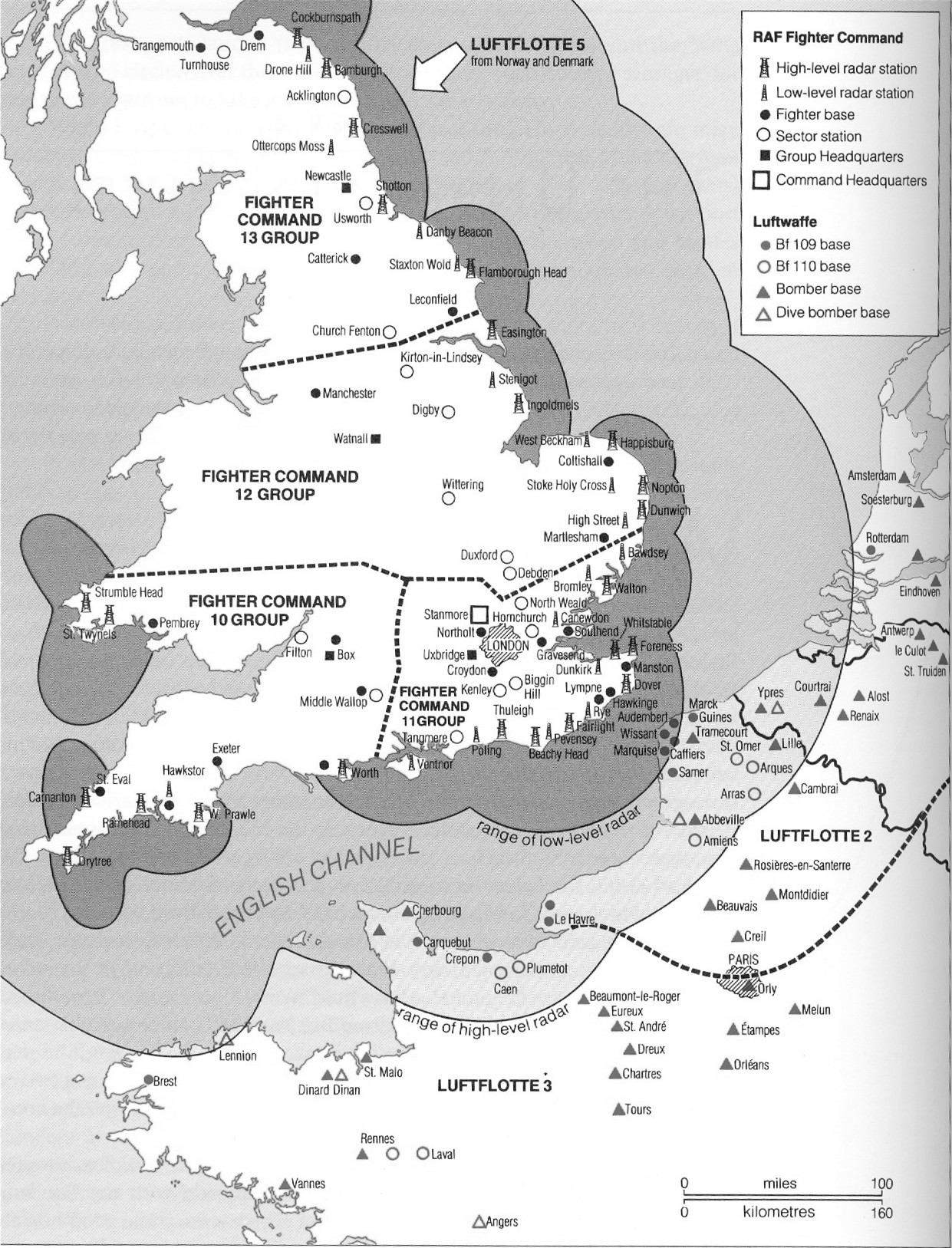

Fighter Command divided Britain into groups, each with a specific defensive commitment. 11 Group was responsible for London and the south-east, 12 the Midlands and industrial north, and 13 Group the rest of northern England and Scotland, with 10 Group, added in July 1940, covering the West Country. Fighter Command’s overall Commander-in-Chief was Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, who, together with the then Air Commodore Keith Park, was largely responsible for creating the radar-integrated System of Fighter Control, created during the 1930s. Before the war, it was anticipated that any air attack on Britain would come from bases in Germany, by unescorted bombers, across the North Sea to the East coast. That being so, 12 Group would have been the frontline, but Hitler’s unprecedented advance to the Channel coast changed everything: with bases in north-west France, London was within the Me 109 fighter’s range, meaning that German bombers could be escorted to and from the capital – making 11 Group the hot zone. By 1940, 11 Group’s commander was the newly promoted Air Vice-Marshal Keith Park, whilst 12 Group, now the second line, was the domain of the more senior Air Vice-Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory. The latter, however, had no fighter experience, was jealous of Park, and had a ‘curious enmity’ of Dowding. This did not bide well.

Before the war, before the RAF had combat experience on their new, modern, monoplane fighters, most training exercises concentrated on the flight of two sections of three aircraft, and sometimes the squadron as a whole, which comprised two flights and therefore four sections of three. A ‘wing’ is a formation of either a pair or multiple squadrons, and pre-war there was no emphasis on such formations or training. One reason was because the TR9D radio fitted to aircraft at that time only provided for communication between pilots of one squadron and their ground controller, there being no common frequency. Consequently, it was impossible for a leader in the air to control formations of fighters larger than a single squadron. Over Dunkirk, it had proved necessary to meet the enemy in strength, owing to the size of German fighter sweeps, and squadrons travelled across the Channel in convoy – once battle was joined, however, they operated individually as cohesion was lost. For those reasons and because there was an urgent need to preserve limited resources whilst executing maximum damage on the enemy, Dowding and Park anticipated defending Britain with small, flexible, formations, able to react swiftly. Indeed, Park’s mantra was that it was better to upset the aim of many, rather than destroy a few.

Whilst Park’s fighters were engaged further forward, 12 Group’s job, in addition to its own defensive responsibilities, was to cover 11 Group’s airfields. 12 Group, therefore, sat largely idly by, whilst early on in the battle 11 Group’s small formations of Spitfires and Hurricanes fought over southern England and the Channel. For Squadron Leader Douglas Bader, commanding 242 Squadron in 12 Group, it was intolerable that he should play a secondary role. Likewise, Air Vice-Marshal Leigh-Mallory was determined to somehow get 12 Group into the action – en masse – before the opportunity for glory passed.

During mid-August 1940, 11 Group requested assistance from 12 Group to protect certain airfields, but Leigh-Mallory’s fighters arrived too late to prevent these vital targets being bombed. Park was furious, and relations between both the two commanders and their groups went downhill from there. On 30 August 1940, 11 Group again requested reinforcements from 12 Group, which was the opportunity Bader had craved. On that day, his Canadian 242 Squadron pounced on German bombers and twin-engined Me 110 fighters, Bader’s Hurricane pilots subsequently making a large number of claims. These were accepted, it seems, with little scrutiny, generated various congratulatory signals. Bader then submitted a report opining that had he more fighters under his control, more of the enemy would have been destroyed. Leigh-Mallory agreed and authorised Bader’s 242 to fly with the Hurricanes of the Czech 310 Squadron and Spitfires of 19. Bader, of course, was the leader, and so the ‘Duxford Wing’ was born – which first went into action over London on 7 September 1940. Caught on the climb by Me 109s, the engagement was not entirely successful, but Leigh-Mallory persevered, adding two more squadrons, to what was now a ‘Big Wing’. Over time, the ‘Big Wing’s’ combat claims were extraordinary, far higher than those of 11 Group’s squadrons, suggesting that mass fighter formations were right – whilst Dowding and Park were wrong.

Neither Dowding and Park were politicians. Both were fighting men determined to defend Britain, as much from political interference as the enemy. Consequently they had both made enemies – ambitious and powerful men who now gathered in the corridors of power, and to whom the argument over tactics was a means of furthering personal agendas. Suffice it to say that shortly after the Battle of Britain, following a shocking political intrigue, Dowding and Park were replaced. Some argue that this was because Park, having just fought a crucial battle, was tired and needed rest, and that Dowding was already well beyond retirement age and, having likewise shouldered an immense burden, had not the energy to get rapidly to grips with the night Blitz. The evidence, however, suggests otherwise – and the bitter row over the Big Wing undoubtedly played no small a part in them going. Indeed, Dowding was replaced by Air Marshal Sholto Douglas, and Park by Leigh-Mallory – both new men supporters of the ‘Big Wing’ concept in both defence and offence.

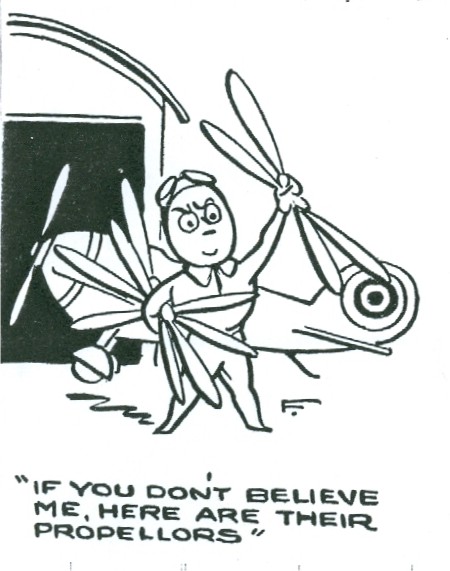

Whilst Bader himself had not personally intended disloyalty, as such, to his Air Officer Commander-in-Chief, Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, he had been, as Lord Dowding later commented, ‘the cause of a lot of the trouble’ – because his ‘Big Wing’ ideas provided Leigh-Mallory the opportunity to get 12 Group a leading role in the battle, and others to criticise Dowding and Park’s tactics at the highest level. The fact, however, is that post-war research confirms that on virtually all occasions it was engaged, the ‘Big Wing’ massively overclaimed, sometimes by a ratio of 7:1. This was because the more aircraft are involved, the greater the confusion, leading to multiple claims. We know now, then, that the ‘Big Wing’ was, in reality, nowhere near as effective as its supporters believed at the time, and that Dowding and Park were absolutely right.

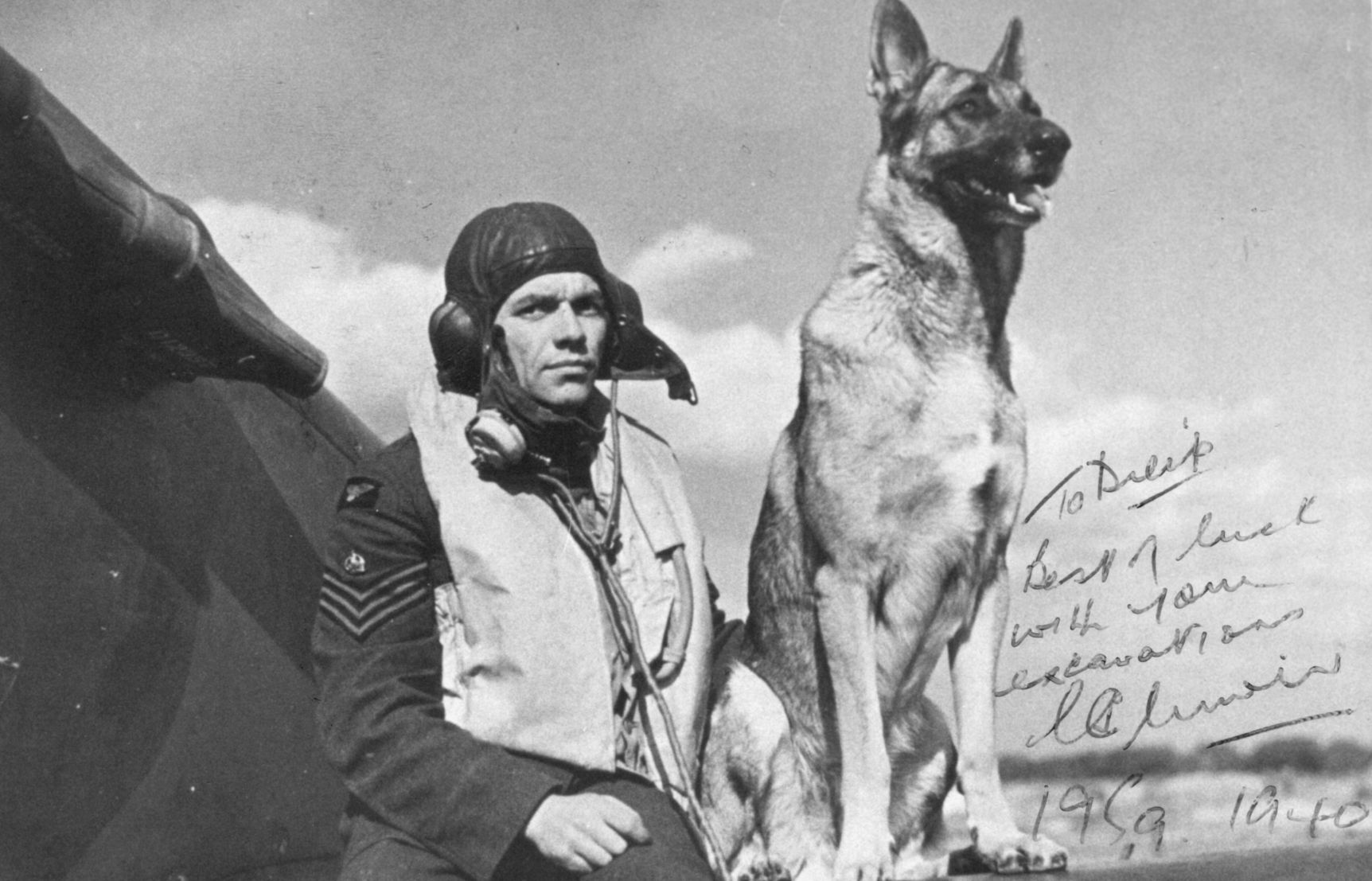

Whereas previous books on the subject have failed to include any critical analysis, in this investigation combat claims have been rigorously considered. Moreover, having personally known surviving supporters and detractors of the ‘Big Wing’ concept, pilots who flew in it and also those in 10 and 11 Groups, I was able to interview these men personally, 25 years ago. These accounts are unique recollections and impressions of those there at the time, presented alongside the actual hard facts. Like those first-hand accounts, then, this book is equally unique in the Battle of Britain’s extensive bibliography. This book, therefore, is not a romanticised tale. It is based upon factual evidence – which often departs substantially from the popular narrative – and investigates a distasteful thread of the Battle of Britain story.

Some might ask why any of this is important, over eighty years after the event? To me, history needs to told, and in this case the adoption of wings as standard practice by Douglas and Leigh-Mallory had seriously negative implications for Fighter Command in 1941 (explored in detail in my forthcoming Bader’s Spitfire Wing: Tangmere, 1941). The ‘Big Wing’ story and significance of it remains largely misunderstood by enthusiasts and students of the Battle of Britain, in my experience, and yet it is crucial to understanding the wider story. The former Under-Secretary-of-State for Air, Harold Balfour, perhaps summed it up best: ‘… for it is history, and all history is important’…

Dilip Sarkar MBE FRHistS, 23 November 2021

More on Group Captain Sir Douglas Bader here, on Dilip’s website

And on Dilip’s YouTube Channel

Follow Dilip Sarkar on Facebook and Twitter

Order Bader’s Big Wing Controversy here

(All photos Dilip Sarkar Archive)