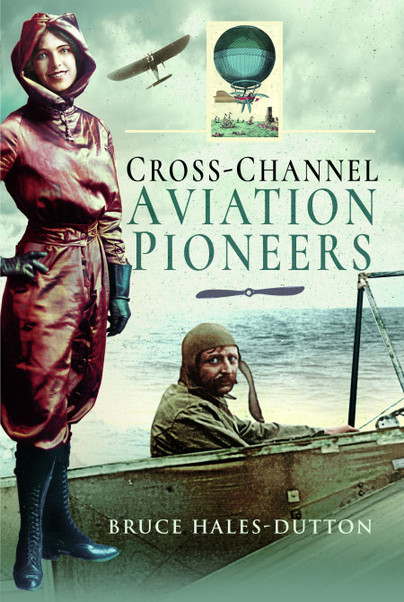

Guest Post: Bruce Hales-Dutton

LATHAM’S LUCK

In his Norfolk jacket, stiff collar, tweed cap, gloves and polished brogues with a cigarette permanently dangling from his lips he epitomised early 20th century cool.

But then Arthur Charles Hubert Latham also combined show with go. Pioneer motorist, aviator, big-game hunter, explorer, man-about-town: Hubert Latham was all of these things.

And with a British father and French mother he represented an exotic fusing of two cultures. Despite his Oxford education, however, he considered himself French. His father had died comparatively young and Hubert had lived much of his life switching between an imposing country chateau and an elegant apartment in a fashionable district of Paris near the Arc de Triomphe.

Yet Latham was unlucky. Louis Bleriot and the Hon Charles Rolls have been feted down the ages for being, respectively, the first man to fly the Channel in an aeroplane and the first to make a double crossing. But Hubert Latham is best remembered for being the man who didn’t quite make it.

Bleriot’s feat is commemorated by a stone marking the spot where he landed on 25 July 1909 near Dover Castle while Rolls’ statue on Marine Parade looks out over the harbour. Louis Bleriot changed the world; Latham just got his feet wet.

If his elegant Antionette monoplane powered by a relatively powerful V8 engine looked the part, Bleriot’s stubby machine with its puny air-cooled three-cylinder Anzani had an unfinished look about it. Yet for all its sophistication it was the Antionette that fell short. Twice.

Latham took off from Sangatte at around 06:40 hr on 19 July. But just as Latham had climbed to 1,000ft his engine started to misfire. He tried all the electrical connections within his reach as well as the fuel and air supplies to the engine. It was in vain. He had to bring his aircraft down on the water to as smooth a landing as he could manage. He was just eight miles from the French coast.

On 25 July Latham tried again with a new Antionette. He’d asked to be roused early but was not called until 05:00 by which time Bleriot had already left. But then the wind rose, preventing Latham from following his rival. That day the luck was with Bleriot. He’d seized the only calm interval in several days of storm.

Two days later the weather cleared and late in the afternoon, Latham set out on his second attempt to fly the English Channel. The news of his departure was transmitted to Dover where 40,000 people gathered on the cliffs to watch him land. When he was spotted approaching the English coast the ships sounded their sirens and the crowd cheered itself hoarse. But fortune was still against Hubert Latham.

With success almost within his grasp the Antoinette engine failed again and once more he was forced to land in the sea. This time he’d almost reached the white cliffs but it was another heroic failure. The machine landed heavily in the choppy water and Latham was thrown forward on impact, hitting a strut. His goggles were smashed and shards of glass cut deeply into his nose and forehead. After his rescue a house surgeon from Dover Hospital put five stitches into his face. He’d finally reached Dover but not the way he’d hoped.

Latham made no further attempts to fly the Channel, instead turning his attention to displays of flying skill at the aviation meetings which were growing in popularity.

Despite his daredevil exploits Latham didn’t meet his end in a flying accident. In 1912 he was big game hunting in the French Congo when he was killed in circumstances that have never been satisfactorily established. The official version is that his rifle jammed at a critical moment and that he was tossed three times by a wounded buffalo. It seemed that luck had again deserted him at a critical moment.

But Hubert Latham, Louis Bleriot and Charles Rolls were far from being the only amazing personalities associated with pioneering cross-Channel flying. As I’ve tried to show in Cross-Channel Aviation Pioneers, Bleriot was just the first. New ways of flying across the 22 miles of water separating Britain and France are still being found.

In 2011 Anglo-American balloonist Jonathan Trappe crossed the Channel beneath a cluster of helium-filled balloons. After what was described as a “goofy yet mesmerizing stunt”, a reporter asked Trappe what it felt like to have conquered the Channel. He retorted: “We have not conquered the Channel. We have only had the honour to float in the skies above the cold waters for one quiet day. Today and forever, the English Channel remains unconquered.”

Hubert Latham would probably have agreed.

Cross-Channel Aviation Pioneers is available to order now from Pen and Sword Books.