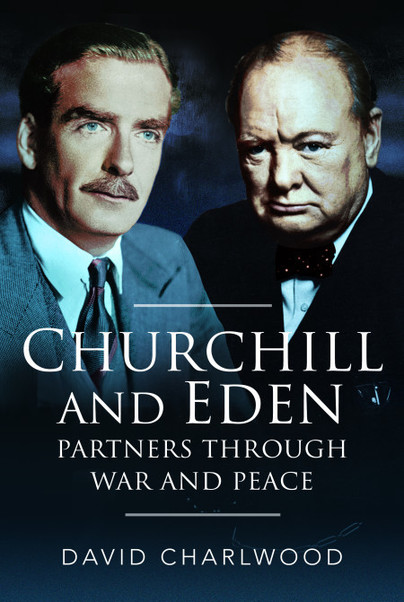

Guest Post: David Charlwood

Author draws comparison between modern day politicians and Churchill and Eden

“Future PM” Sunak should be careful what he wishes for: Boris might turn out to be like Churchill

The public now think Rishi Sunak would make a better prime minister than Boris (according to polls). He appears to have a grasp of the details, is more popular among non-Tory voters and ‘Dishy’ Sunak also looks better in a suit. But if the Chancellor of the Exchequer has ambitions to move next door, he should be mindful of what happened to a similarly regarded politician a few generations ago. Anthony Eden was for years Winston Churchill’s successor in waiting, but the reins of power had to be prized from his grasp.

A French newspaper once voted Eden ‘best-dressed Englishman’. He was urbane, attractive, had an Oxford degree and quickly became a political high flier. When first appointed Foreign Secretary in 1939 at the age of thirty-eight, he was the youngest man to hold the post since before the Crimean War. Rishi Sunak is one of the youngest Chancellors in history, also an Oxford graduate, and a politician who is being touted in the press as prime ministerial material. He is also right-hand man to a leader currently under fire for their management of a ‘wartime’ crisis.

Boris Johnson is facing growing criticism of the government’s handling of the Coronavirus pandemic, a battle that the prime minister has repeatedly compared to a conflict. ‘It’s like a war effort’, he told the BBC in March 2020, ‘it is a war against this virus.’ It is no secret that Winston Churchill is an idol of Boris Johnson’s – the PM has even written a biography of Churchill – and like Churchill, Boris is now leading the United Kingdom through a crisis.

History has painted Churchill’s wartime premiership as an unalloyed success, but he faced serious opposition in the summer of 1942. Britain was in the midst of war and the war was going badly. In North Africa, the Libyan city of Tobruk had fallen to German general Rommel’s forces and 33,000 British Army soldiers had been taken prisoner. In addition, the Battle of the Atlantic was still on knife edge and the British had lost the ability to read U-boat cipher signals after the German navy had changed their Enigma code machine settings. Churchill had acquired the dual role of both Prime Minister and Minister of Defence and concentrated considerable powers of decision in the hands of one man. The centralisation of decision-making at the expense of input from Parliament and MPs was deeply controversial. And it also seemed to be having a detrimental impact on the outcome. Privately, Eden was as appalled as many other observers at the results, recording in his diary, ‘He [Churchill] sees himself … as the sole director of war’. In a letter to a friend Eden confided, ‘Brilliant improvisation is not substitute for carefully planned dispositions’, adding that what troubled him most was that he and other Cabinet members ‘are regarded by [the] public as those running the war, and we don’t one little bit.’ Eden was seen by backbenchers as the natural successor and the counter to Churchill’s dictatorial leadership style. He was approached and sounded out, but rebuffed suggestions that he should conspire to stab Churchill in the back. When one backbencher openly suggested to him that Churchill should go and he should take his place, Eden replied he ‘would do no plotting against Winston, now, or ever’.

By the end of the Second World War, as the first election since the outbreak of hostilities approached, it was clear that Churchill assumed he would win easily. Eden was less sure and also questioned whether he even wanted to keep his senior Cabinet position if the Conservatives won. He recorded in his diary, ‘Am beginning to seriously doubt whether I can take on F[oreign] O[ffice] work again. It is not work itself which I could not handle, but racket with Winston at all hours! He has to be headed off so many follies.’ In the event, the voters shocked pundits and many politicians and delivered a landslide for Labour’s Clement Attlee.

It was a catastrophic election defeat that many assumed would lead to Churchill’s resignation as party leader, paving the way for Eden to take over. When Eden met with key Conservatives to discuss the future of the leadership, he was amazed that they had misjudged Churchill. They ‘apparently thought that Winston would retire to write books, make only occasional great speeches and hand over the leadership’, he noted, ‘… this was not Winston’s idea at all.’ Churchill clung on, leaving Eden to do the vast majority of the day-to-day work of leadership, and as the chance of another term increased, so did his personal determination. In 1951, the Tories overturned Labour and Churchill again became prime minister at the age of seventy-seven.

During Churchill’s second term it became increasingly obvious that the most popular politician of his day did not have the grip of affairs needed to govern. Churchill was often absent from Cabinet meetings, with one civil servant remarking privately that when he did chair them, the meetings were ‘slow, waffling and indecisive’. On multiple occasions Churchill promised to step down, before changing his mind at the last minute. Although they remained personally close, the political relationship between Churchill and Eden became characterised by constant conflict. Finally, ten years after the end of the war, Churchill stepped aside. When the moment came, he could not bring himself to address Eden directly. He turned to Rab Butler, then Chancellor, who was also in the room, and said simply, ‘I am going and Anthony will succeed me. We can discuss details later.’

After decades of waiting in the wings, Eden finally became prime minister in April 1955. But within two years he was forced to step down due to ill health and the foreign policy disaster of the Suez Crisis, for which he was significantly individually culpable. Rishi Sunak is currently the Tory party’s Eden: popular, eloquent and an obvious future PM. He may well hope Boris does not turn out to be like Churchill.

David Charlwood is the author of Churchill and Eden: Partners Through War and Peace

Order a copy here.