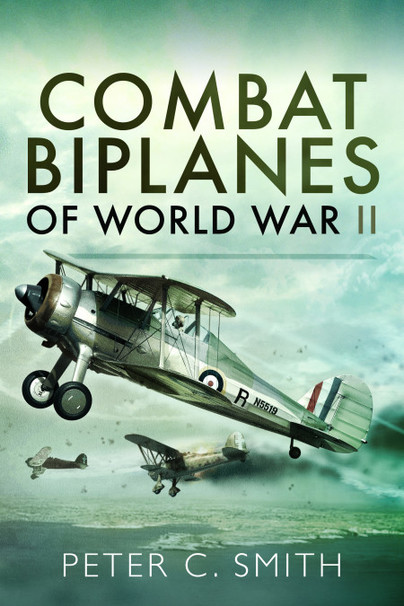

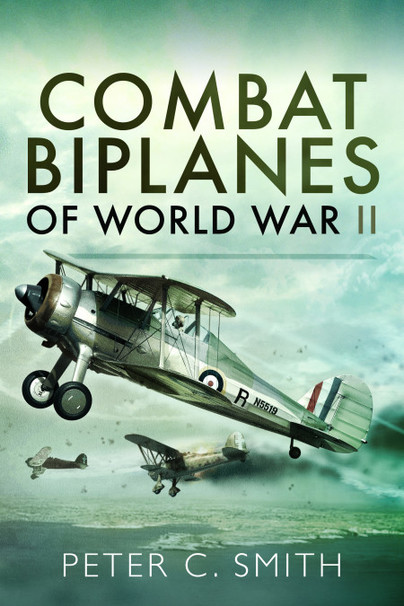

Guest Post: Peter C Smith – US Navy Biplanes

The United States was propelled into World War II by the surprise Japanese attack on the Naval base at Pearl Harbor in the Hawaii Islands on 7th December 1941. The very last United States operational biplane combat fighter plane of any military service had been the Grumman F3F-3, of which the Dash-3 version had been assigned to the aircraft carrier Yorktown (CV-3), but from which the last one had been retired from front-line service in November 1941.1 Thus, in terms of aerial battles, the American Air Forces of the Navy, Army and Marine Corps did not strictly qualify for inclusion in my book Combat Biplanes of World War II.

However, one military biplane did see considerable service throughout that conflict, albeit as a scouting, anti-submarine and target spotting aircraft, mainly in the Pacific Theatre of War.

One of the most widespread of the United States Navy’s biplanes in the opening months of World War II was the Curtiss SOC-1, which was later named as the Seagull. Curtiss had long specialised in amphibious aircraft and was a natural provider of the Navy’s requirements in this field.

Launched by catapult from the fleet’s battleships and cruisers, the principal duties envisaged for this type of small floatplane was to provide “spotting” of enemy targets, both enemy naval units at sea, and shore targets on land for bombardments. They were also employed on short-range scouting duties, and for this duty the Seagull had a maximum range of 846 miles at cruising speed. They could also carry out limited anti-submarine patrols around the ships, although their sole anti-submarine equipment was initially only two 100lb bombs of doubtful value.

On completion of a sortie, recovery was by a sea landing and then by way of the onboard crane(s). Thus, their scope was limited by the weather and sea conditions, although they would have been considered “expendable” in urgent battle circumstances. Carrier-born aircraft could do this duty of course, but in the American Navy the accepted emphasis was for all available carrier planes to deliver the maximum punch by getting in the first blow according to established naval aviation doctrine. The reconnaissance task could also have been done by the bigger multi-engine seaplanes, which had a much greater longer reach, but these were still tethered to island bases and these were few and far between in the vast Pacific where the main opponent was always deemed to be the Imperial Japanese Navy, 2 and the long-range Consolidated Catalinas based on Midway, Noumea and the like, were sometimes employed for this mission.

The battleships and the bigger heavy cruisers could carry several such aircraft, eight maximum aboard battleships and up to a maximum of four in the bigger cruisers, both in wartime mode, usually with two or more ready to be employed on their launch apparatus, with others stowed in hangars aboard. While battleships and the new big cruisers usually carried their launching catapults aft, (of the Type P – of various later marks), or amidships on the older heavy cruisers, the much smaller Omaha Class light cruisers, due to the restrictions of space, carried their catapults on two elevated towers amidships.

Many skippers had mixed feelings about these aircraft, a worry shared by all such operators, in that they were considered a very great fire hazard with the aviation fuel and stowage. Battleships, perforce, had an AVGAS pipe running from the gasoline storage bunker right along the ship to their aft location, which also did not lessen this worry. Also of course, the aircraft, during surface actions or under aerial attack, were to prove highly vulnerable to blast from bombs and shells and often had to be ditched or sent ashore for repair after such damage, while their parent ship remained unscathed. 3

These type of small floatplanes had folding wings, with the smaller balancing floats outboard on the underside of the lower wing. A fully folded Seagull would pack down into 12.5 feet of storage. For land-based operations the single main fuselage float could be replaced by wheels. They had a two-main crew, the pilot and an observer/radio operator seated in tandem. Main power plant was a 550 hp Pratt & Whitney R-1340 radial engine, driving a Curtiss 9-ft diameter propeller. Defensive fire was very limited with two 0.30-6 calibre M-1919 machine guns, one firing forward from the fuselage with other on a flexible mount utilised by the Observer.

For the types of mission envisaged, the Seagull was prosaic enough. Her principal dimensions were a wingspan of 36ft, an overall length of 31ft 9 in and a height of 14ft 1in. The Wing area was 348 sq. ft and she weighed 3788lbs unladen and 5153 lbs fully loaded. Her service ceiling was 15,000 ft she could climb at a rate of 5.9 minutes up to 5,000ft.

This sturdy little biplane was first delivered to the fleet on 12th November 1935, when one went aboard the light cruiser Marblehead (CL-12) for trials. She proved an instant success and by June of the following year was supplied to five VS Scouting Squadrons – VS5B, VS-6B, VS9S, BVS-11S and VS12S, as well as going aboard the light cruisers Memphis (CL-13) and Raleigh (CL-7) and the heavy cruisers Augusta (CA-31) and Indianapolis (CA-35). Some 135 of this initial model were finally built and they replaced the Vought O2V and O3V Corsair then in service. By 1940 almost every commissioned battleship and cruiser and some seaplane tenders, was employing the Seagull This initial variant was followed by the SOC-2 of which forty were constructed. They differed principally by the introduction of the R-1830-22 Wasp engine.

The SOC-3, numbering eighty-three machines, followed.

Another batch of four aircraft were built for the United States Coast Guard, this was the SOC-4. This quartet was later taken over by the US Navy and modified to become the SOC-3A.

Meanwhile, following then current US Navy practice to ensure duplication of manufacture, the Naval Aircraft Factory at Philadelphia, built a further 44 aircraft, known as the SON-1.

By 1939 and the outbreak of war in Europe, all Observation units had the Seagull as part of their establishment. Developments during the war saw the Seagull toting two Mk 17 depth-charges for anti-submarine work, which was a more realistic weapon for this job.

Perhaps the most difficult operational problem for the Seagull, as with all such floatplanes employed at sea, was the actual recovery, which was deemed dangerous and time-consuming. However, one SOC pilot described it to me how it was done in practice. “The Captain and the OOD would head the ship about 25 degrees to starboard of the wind line, then hoist a flag indicating aircraft recovery operations in affect. The SOC to be recovered would sees the flag so the pilot flies up the starboard side of the ship at 500ft altitude. When the SOC is at this point the ship two-blocks the flag and commences to turn the ship to port through the wind line to degrees to port of the wind line. The manoeuvre by the ship is supposed to cause a slick to form which the pilot is supposed to land in. The pilot then taxis the SOC up the port side of the ship for a port recovery, or up the starboard side of the ship for a starboard recovery. The one main crane, located amidships, then lowers to the SOC so it can be attached to the upper wing of the SOC. The Radioman then stands over the pilot and hooks the crane to the hook on the upper wing. The SOC is then put on one of the two catapults on either side of the ship’s well deck. This recovery operation could take between 15 and 30 minutes.”4

Training for the floatplanes of the US Navy was initially conducted at Naval Air Stations Jacksonville and Pensacola, both in Florida. Later another facility was opened at Corpus Christi, Texas. Primary training was carried out the by another biplane, the Naval Aircraft Factory N3N Canary (Nicknamed as the “Yellow Peril” from her all-over bright yellow “training” paint scheme). She had the exactly the same under-fuselage large float and two smaller lower wingtip-mounted balancing floats, and tandem aircrew accommodation, as the SOC. Some 179 N3N1’s were built and 816 N3N-3’s, along with a few intermediaries. With a Wright-R-760-2 Whirlwind radial power plant giving her a top speed of 126mph, she proved to be the very last biplane aircraft to remain in service with any US Military service, being introduced in 1936 and not finally retired until 1961.

For afloat training, the USS Absecon (AVP-23), a Barnegat Class Seaplane Tender, was converted into a specialist float plane training ship and she carried two cranes right aft and a Type P catapult (surplus equipment from a cancelled Cleveland class cruiser) positioned ahead of them. She was based at Naval Air Station Port Everglades, Florida, in this role and later moved to NAS Pensacola. [f/n – Between 1943 and 1946 Absecon carried out several thousand successful launches and only lost five aircraft in the process. She was decommissioned in 1947 and transferred to the United States Coast Guard.]

Mention should be briefly be made of the Curtiss SO3C Seamew. Intended to be a faster Scout Observation shipborne floatplane to replace the Seagull, this aircraft, of which eight hundred were eventually built, proved to be a big disappointment in service. This machine was a monoplane so has no real place here except for the that she had a great many design faults, and so poor an aircraft was she considered, (her aircrew derisively named her ‘Sea Cow’ so unpopular did she prove) that she was withdrawn from front-line service in 1943, and the Seagulls had to be brought back to the fleet from their training role, to replace at sea once more. Thus, this failure ensured the longevity of the Seagull herself and they were still serving aboard many US Navy cruisers, like the San Francisco (CA-38), during the immediate post-war period 1945-46.

© Peter C Smith, May 2020.

f/n 1– A few continued operations in secondary, non-combat, roles until November 1943.

f/n 2 – At the Battle of Midway in 1942, Admiral Frank Fletcher, (a cruiser man first-and-foremost) employed some his carrier bombers to carry out a short-range scouting mission on the first morning, but this left the Yorktown short for her first vital air strike, and also delayed the other two American carriers by a crucial time period. His two heavy cruisers, Astoria (CA-34) and Portland (CA-33), were ordered NOT to launch their patrol floatplanes, “… we pilots were told that we would not fly until early Friday 5 June,” – SOC pilot, Ralph Vincent Wilhelm to the Author 23rd March 2009.

f/n 3 – This was a problem common to all navies of course, the Royal Navy heavy cruiser Exeter had both her Walrus aircraft damaged by shell fire from the Admiral Graf Spee at the Battle of the River Plate in 1939, and had to embark a replacement one from the heavy cruiser Cumberland after the battle – which aircraft she retained after being repaired. After losing one of two allocated Walrus to an accident in the Indian Ocean in 1941, Exeter had replaced it by embarking the one surviving Walrus from the battle-cruiser Repulse at Singapore, after that latter ship had been sunk. But this aircraft in turn was damaged by bomb blast from Japanese aircraft on the 30th January and had to be sent ashore in Java to repair, while her original Walrus was later also damaged in the same way prior Exeter’s final sortie and loss in March.

f/n 4 – SOC pilot, Ralph Vincent Wilhelm to the Author 23rd March 2009.

Combat Biplanes of World War II is available to order here.