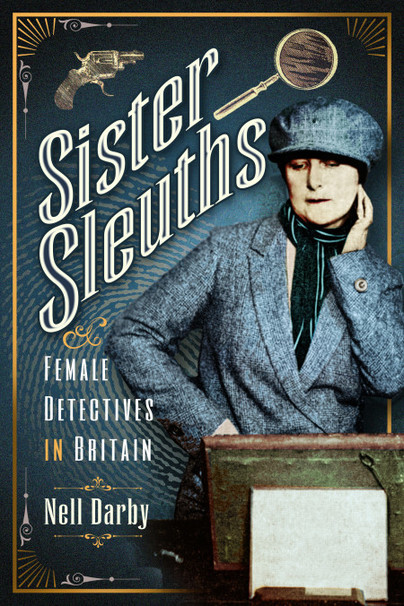

Sister Sleuth: The Woman Who Spied For A Living

Author guest from Dr Nell Darby.

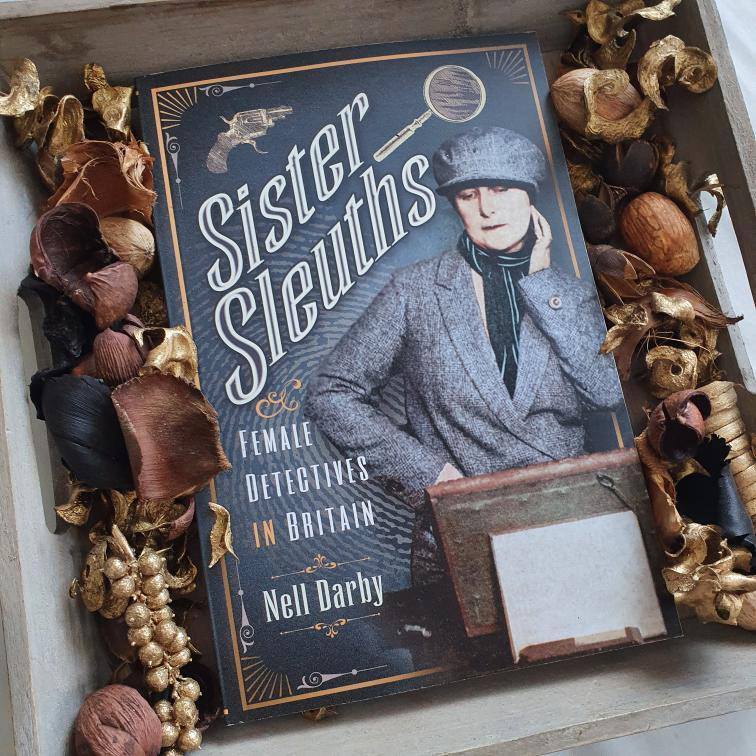

When I was researching my book Sister Sleuths: Detectives in Britain, 1850-1950 (Pen & Sword, 2021), I wasn’t surprised by how many women became private detectives in the 19th and 20th centuries. Women have always been regarded as inquisitive, curious about the world around them and the people they live amongst. Becoming private detectives has long been a way to put this curiosity to good use. To find out about others, to shadow individuals, to develop friendships with people so that you can find out information about them: these have been key aspects of a private detective’s work over the past two centuries that have enabled women to become successful workers in the field.

The bread-and-butter work of the private detective by the end of the 19th century was in divorce work. When a man or woman petitioned their partner for divorce, they needed evidence of their spouse’s bad behaviour, and adultery was a key part of this. Many a married person would commission a private detective to watch, or ‘shadow’, their spouse to try and find evidence of them having a relationship with another person. Although detectives are rarely mentioned in a divorce petition, press coverage of such cases frequently report private detectives giving evidence in court. What court cases and newspaper reports show is that women were keen to work as private detectives on such cases.

One of the most interesting female private detectives I researched for my book was Antonia Williamson, a woman from a wealthy middle-class family. Married off to her first cousin, she was unhappy with the expectation that she should be content just as a wife and mother. Desperate to do something to keep her intellectually stimulated, within a year of her marriage, Antonia went to a private detective agency and asked for a job. In doing so, she echoed Kate Easton, who nearly half a century earlier had turned up door Allan Pinkerton’s door in Chicago in search of work, and who arguably became America’s first female private detective.

The agency approached by Antonia was run by Maurice Moser, a former police detective. He gave her a job, but the couple then started an affair, which scandalised society and led to their respective spouses divorcing them. The couple lived together – Antonia claimed they were married, but there is no evidence of this – and joined forces to run a detective agency together. When they later split up, amidst allegations of domestic violence, they became competitors, with Antonia running her own agency not far from her ex-partner’s. Although some were critical of women working as private detectives – seeing them as too ‘excitable’ or ‘sentimental’ to work effectively – Antonia held no truck with such views. As she once noted, “There are women criminals as well as men, and there seems no logical reason why women should not deal with them.”

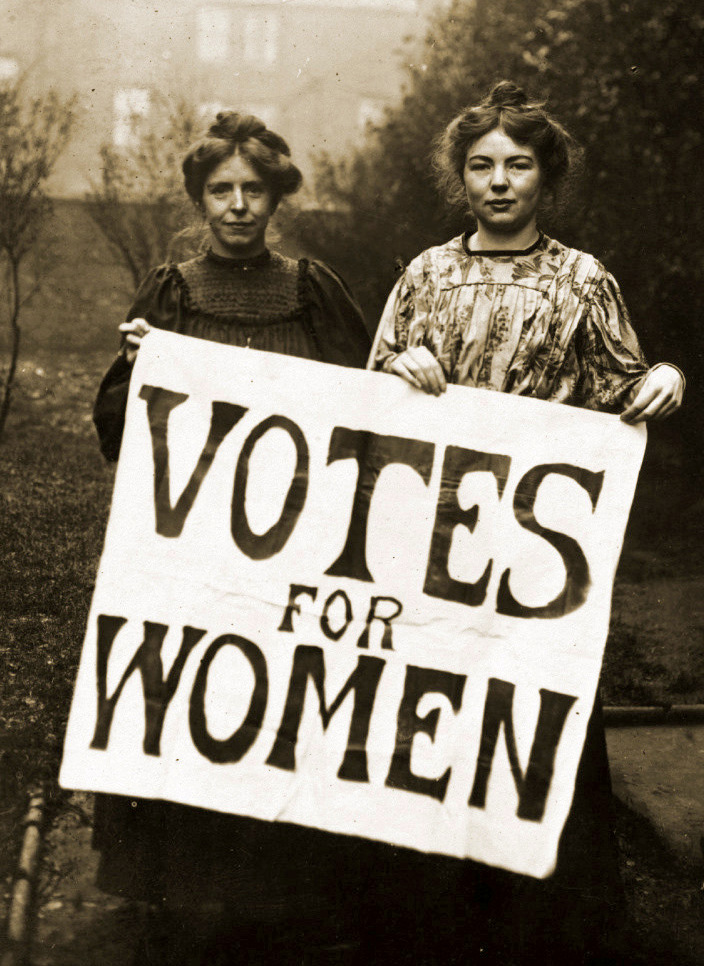

Antonia strongly believed that women should have the same opportunities as men. She was a keen supporter of women’s suffrage, corresponding with key suffragists, and later marketing herself as a source of personal and financial advice for women. She argued that a woman “makes as good a detective as a man, and often a better [one]”, and worked to put this belief into practice.

Although many private detectives, like the Mosers, had their own agencies and offices, others worked on a smaller scale, operating from home. This made it an achievable career for some women with caring responsibilities, who seem to have worked part-time from their homes, sending out enquiries from their parlours, and going out to shadow individuals when their children were at school. Antonia had her own office, although this changed location over time. For much of her career, she was based around the Strand in London. This was a popular location for detectives; not too far from the Royal Courts of Justice, where divorce cases were heard in the Divorce Division, but also close to many of London’s theatres, a centre of scandal and gossip.

Private detectives needed to make sure that the public knew of their existence in order to get work, and Antonia was aware of how vital marketing was in her industry. This was especially so for women, who had less of a reputation than some of their male equivalents. Antonia’s former partner Maurice Moser was well-known from his time in the Metropolitan Police; he was also good at marketing himself, writing articles and memoirs about his experiences and claiming expertise and results that were hard to prove or disprove. It made sense for Antonia to adopt his name professionally; people would link her to the successful male detective because of the relatively unusual name, and assume that she was as successful as he.

Many detectives advertised their services in the newspapers, again emphasising or exaggerating their experience. Antonia duly advertised herself in the London press in 1905 as ‘Antonia Moser, Detective Expert’, stressing that she was ‘prompt, secret, and reliable’. Luckily, newspapers were fascinated by the existence of female detectives; they were seen as daring, different, not like other women. In 1907, Antonia wrote a series of articles entitled ‘The Thrilling Adventures of a Woman Detective’ for the Weekly Dispatch newspaper. These shed light on the day-to-day life of a female detective in Edwardian London. Antonia described how she would be sitting in her inner office working, only for her clerk to bring calling cards into her, with scribbled lines on them asking ‘to see Mrs Moser urgently’. If Antonia was interested, she would tell her clerk to bring in the card’s owner, and she would then interview them about what their needs. Her description of one of these potential clients makes it clear that some men did not take female detectives seriously: “For a moment the thought crossed my mind that I was dealing with some would-be facetious person who thought to amuse himself at my expense.”

Antonia was keen to dissuade readers that the bulk of many a detective’s job involved spying on married couples. Her weekly series detailed cases including the disappearance of a rich woman; a series of swindles; and a man who had woken up in a hotel with no memory of how he had got there, having been drugged by adventurers the night before. She presented herself as a successful woman who employed other people to work for her, and who was always busy. Her stories may have been true, but they were equally likely to have been exaggerations or even fictional, designed to present the image of Antonia Moser that she wanted to present. Although she died in 1919, Antonia left behind fascinating clues as to her detective career, and remains a fascinating figure for me.

Sister Sleuths is available to order here.