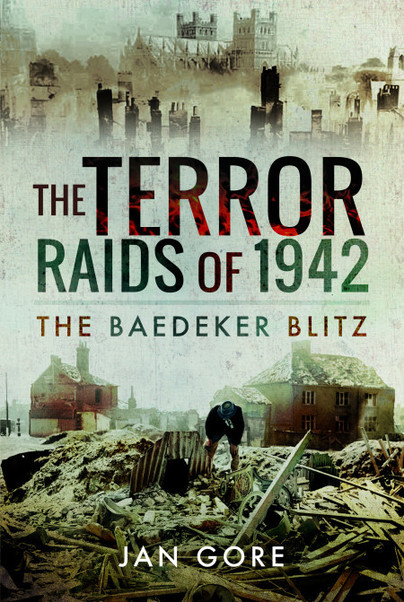

The terror raids of 1942: the Baedeker Blitz, by Jan Gore

‘We shall go out and bomb every building in Britain marked with three stars in the Baedeker Guide’ the German Foreign Office announced in April 1942, as the Luftwaffe attacked Exeter, Bath, Norwich, York and Canterbury. This might have been a challenge, as there were no three star buildings in the guide. Nevertheless, it was this comment that gave the Baedeker Blitz its name.

These attacks were direct retaliation for RAF raids on equally historic German cities, such as Lübeck. Hitler ordered that ‘Preference is to be given…where attacks are likely to have the greatest possible effect on civilian life’ and in this narrow aim they certainly succeeded. My book is the first full history of the raids for over twenty years. It describes the Baedeker Blitz from the point of view of the civilians who were its target, with graphic first-hand accounts and contemporary news stories.

Nine days after Hitler’s order, the raids began. The first target was Exeter, on 23 April. Only one bomber hit the city. It was not until the British authorities intercepted a message from a reconnaissance aircraft the following morning that they realised this had been intended as the first of the reprisal raids. However, the next attack on Exeter was very different.

Just after midnight on Friday 24 April there was a raid lasting almost two hours. About sixty HE bombs were dropped along with as many as 2,000 incendiaries. Seventy-three people were killed, fifty-four injured and about 6,000 houses damaged. This later became known as the ‘Minor Blitz’. First-hand accounts described the raid as terrifying. Whole families died in the bombing: grandparents, parents and children. There was a further attack on 26 April; after that ever more people took shelter each night, or trekked out into the hills, sheltering under the hedges, face down to avoid being seen by enemy aircraft.

Meanwhile the German Foreign Office referred to the Baedeker Guide when announcing the Luftwaffe plans. From then on newspapers began to describe the attacks as the Baedeker Blitz. RAF Bomber Command then attacked Rostock on four consecutive nights; British Intelligence were sure the Luftwaffe would take revenge.

On the nights of 25 and 26 April, Bath was attacked in a series of brutal raids. In the first raid, about ninety people died. The actress Helen Shingler had just finished her performance at the Theatre Royal; when she looked out of the stage door she could see Luftwaffe bombers flying so low they could pick off pedestrians in the street with machine-gun fire. The bombers returned to base to refuel and rearm, but they were soon over Bath once more, with the fires left by the first raid helping to illuminate their targets. It was dawn before the all clear sounded, and by then another 150 people had died. Several public air raid shelters were hit, with heavy casualties. And then the Luftwaffe came back, less than 24 hours later, in another huge raid that lasted almost ninety minutes. Over 160 people died this time; the final death toll was over 400 people, with almost 900 injured. “Hitler’s attempt to create maximum terror with limited means”, as one newspaper described it.

The following day, 27 April, the Luftwaffe moved some of their units to the Netherlands. This enabled them to launch an attack on Norwich that night which lasted almost two hours. Over 162 people died and 600 were wounded. Eric Jarrold, just fifteen at the time and a civil defence messenger, described the noise as terrific; he could see the aircraft as they went over, while the bombs fell at a rate of one per minute.

The next target was York. The station was badly damaged and there was a direct hit on the Bar Convent that killed five nuns; a survivor, Mother Andrew, wrote a poignant account of her experiences. 110 people died. The Luftwaffe left at about 4 am on 29 April; that evening they returned to Norwich for a second attack. Sixty-nine people died and many homes and buildings were damaged, including the Norwich Hippodrome, where the stage manager, his wife and two sea lion trainers lost their lives. There was another minor attack on the morning of 1 May, which must have been terrifying for the inhabitants; incendiary bombs nearly gutted the shopping centre.

Monday 4 May was to become known as the Exeter Blitz. In the early hours of the morning, the Luftwaffe launched a devastating attack, starting with incendiaries and then combining these with high-explosive bombs and machine-gunning. At one point there were over 500 separate fires; many burned on for days. 164 people died, 563 were injured and much of the centre of the city was destroyed. Several people spoke of their firm conviction that the Germans would return the following night to “finish the job”; a doctor’s wife drove to Dartmoor to take her sons to safety before returning to the city. She feared she would never see them again.

There was a lull for some weeks. At the end of May, the RAF launched a thousand bomber raid on Cologne. 470 people died and 45,000 were made homeless; ninety percent of the city was flattened. This time there was a new target for reprisal raids: Canterbury.

On the night of 1 June it was hit by flares, incendiaries and HE bombs; there was considerable fire damage and over fifty died, with 1500 buildings seriously damaged. Three further raids occurred during the same week. After that, it was thought the Baedeker raids had ended. However, there was one last reprisal raid; the RAF raid on Bremen on 25-26 June prompted a final attack on Norwich on 27 June, the so-called “fire raid” with over 20,000 incendiaries, a number of deaths and damage to properties.

In all, more than 1,000 people died in the raids, and almost 2,700 were injured. Many historic buildings were lost, but contemporary newspaper coverage suggests the attacks produced a spirit of defiance rather than damaging morale. Nevertheless, the Baedeker Blitz would never be forgotten by those who endured it, as the accounts in my book show.

You can order a copy here.