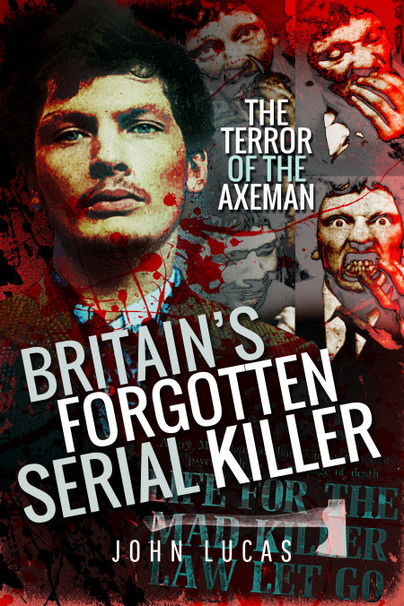

Britain’s Forgotten Serial Killer

Guest post from author John Lucas.

Books are rarely credited with helping to keep a dangerous man behind bars — but thanks to the power of the pen, that’s exactly what happened in the case of Patrick Mackay.

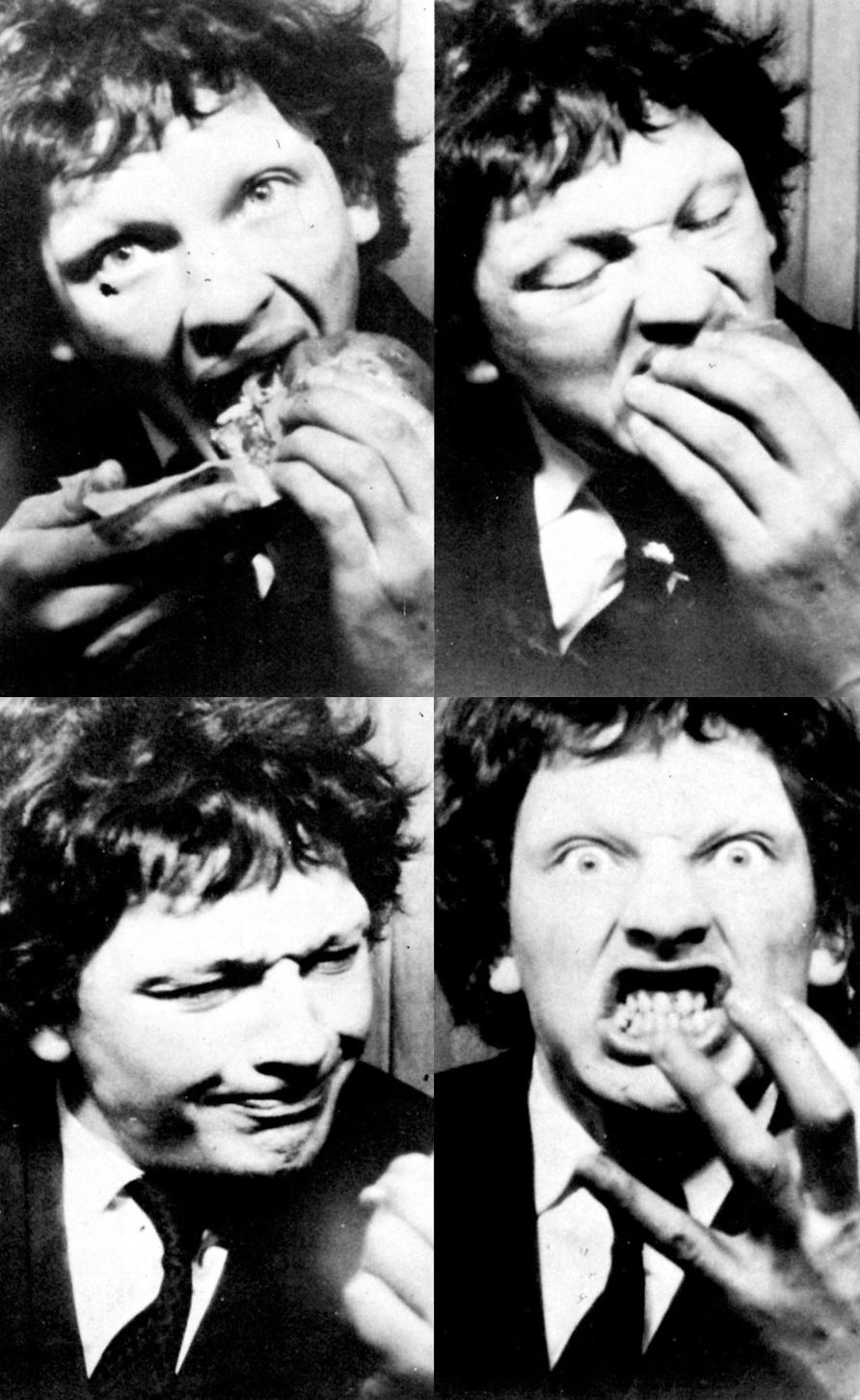

When the maniac was arrested in 1975, a seasoned detective called him one of the “most dangerous and terrifying killers to be walking around London for a long time”.

The deranged, Nazi-obsessed psychopath had killed at least three people, robbed dozens, and was suspected of committing many more brutal crimes, including several murders.

In fact, if Mackay was responsible for only half the crimes he initially confessed to, then it made him (at the time), Britain’s most prolific serial killer since Jack the Ripper.

But thanks to a quirk in his sentencing — as well as the passage of time obscuring the horrific nature of his case — Mackay still realistically hopes to taste freedom in his lifetime.

This is the premise of my book, Britain’s Forgotten Serial Killer, in which I, in part, seek to assess whether or not Mackay should ever be released, given the significant number of unsolved cases still unofficially chalked up against his name.

By publishing the book, I hoped to persuade detectives to reexamine some of his alleged crimes, and to encourage new witnesses to come forward, in light of the fact that he was now living in an open prison and making a fresh bid for release.

In both respects the book — first published in July 2019 — was remarkably successful.

While the case had long since been forgotten by the British public, within days of the publicity material being released it was being discussed in Parliament and gaining national press coverage.

Gareth Johnson, the MP for Mackay’s home town of Dartford, raised the matter and urged the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Cressida Dick, to re-open the seven cold cases under her remit.

He also contacted me to ask for details of the unsolved case, that of Ivy Davies, which fell under Essex Police.

For those unfamiliar with the Mackay story, here is a summary: Patrick Mackay was convicted of three manslaughters, by way of diminished responsibility, and admitted to the murder of a homeless man, whose body was never found and therefore he was not charged. There were two cases, Frank Goodman and Mary Hynes, to which he confessed but then pleaded not guilty when it came to court. They were allowed to lie on file. There were then five other murders for which Mackay was the prime suspect. He allegedly made prison cell confessions but later denied having done so.

Following the publication of the book, I was reliably informed that Essex Police had looked at it [Ivy Davies case] again, although it’s not known whether or not they tested the DNA sample discovered during a previous cold case review, or whether it was even possible to do so.

Another consequence of the book was that two relatives of one of the victims got in touch to ask how they could voice their objections to the Parole Board. I’ve been asked not to disclose their identities, but they did indeed make their voices heard.

This was evident from the Parole Board’s decision, published in May 2021. The document shows that Mackay’s hearing had begun in August 2019, but was adjourned in light of the allegations in the recently-published book. It was eventually reconvened over videolink, because of the pandemic. Mackay, now known as David Groves, asked the Parole Board to release him. They considered his files, which ran to more than 1,700 pages. The panel took evidence from Mackay’s probation officer, a prison psychologist, and other case workers, and he was legally represented as he gave evidence and answered questions. We do not know the content of these exchanges.

The Board made public some previously unknown information, including that Mackay spent the first 27 years of his sentence in Category A conditions, “due to concerns about his behaviour,” indicating that the authorities considered him to be acutely dangerous. Mackay later “demonstrated better behaviour, progressed to lower category prisons and in December 2014 was transferred by the Secretary of State to an open prison following a recommendation by the Parole Board.” However, in May 2015, Mackay was returned to a closed prison “as a result of his difficulties in adjusting to the less restrictive environment of an open prison”. But then in 2017, the Parole Board recommended that Mackay should be returned to an open prison, which happened in November of that year. During this period, Mackay was granted temporary release to spend time in the community. This was only curtailed by the pandemic and not by the serious allegations aired in my book.

As anyone who has read it will grasp, granting temporary release to Patrick Mackay was an extraordinary risk, owing to his propensity to commit offences very soon after being freed from custody – sometimes within hours.

In conclusion, the panel declined to make “findings of fact in respect of the unproven allegations” but said that “based on the evidence available to the panel, it determined that it should disregard some of the allegations. The panel found that it should consider some of the allegations but decided that these did not affect its assessment of Mr Mackay’s risk. However, it did consider that there should be a very cautious approach in respect of Mr Mackay’s rehabilitation.”

It’s not clear what evidence was available to the panel that may have put Mackay in the clear on some of the cases – nothing of this nature has never been made public by the police. While the decision was made not to release Mackay, it was recommended that he could remain in an open prison. Disappointingly, neither the Met not Essex Police made renewed appeals for information over any of the unsolved cases detailed in my book. The Parole Board report concluded: “Mr Mackay will be eligible for another parole review in due course.”

No doubt Patrick Mackay is very bitter about the publication of the book and the effect it has had on his life. What separates most of us from the psychopaths is the ability to empathize, and from his point of view what happened must feel very unfair. After all, Mackay had an awful childhood, blighted by violence, poverty and ill treatment. He’s now spent almost all of his adult life on prison — Mackay was 23 when he was jailed and he’s now in his mid-60s. He became eligible for parole in 1995, but has always been knocked back by the Parole Board.

Yet the facts of his case are stark. Almost every time Mackay was released from custody he committed serious offences, as my book shows, usually within hours or days.

In addition, there is no doubt in my mind — having reported on scores of murders and crimes of serious violence — that if Mackay was tried for his crimes today, when we understand much more about psychopaths than we did back then, that prosecutors would push for murder convictions rather than accept guilty pleas to manslaughter by way of diminished responsibility. As a result, Mackay would almost certainly have been handed a full life sentence, just like notorious killers such as Wayne Couzens, Levi Bellfield, and Peter Sutcliffe — so nobody should feel guilty about doing all they can to ensure that he remains behind bars.

Of course, serial killers like Mackay are rarely seen today, because of the ubiquity of CCTV and mobile phones, which so often allow detectives to pinpoint suspects at the time the crime was committed. Mackay was so careless that he would probably be caught after his first killing. No doubt there are several would-be serial killers in British jails who will one day be released only to re-offend. But that’s a different story, and in my view there is no need to put the public at further risk by releasing Patrick Mackay.

Britain’s Forgotten Serial Killer is available to order here.