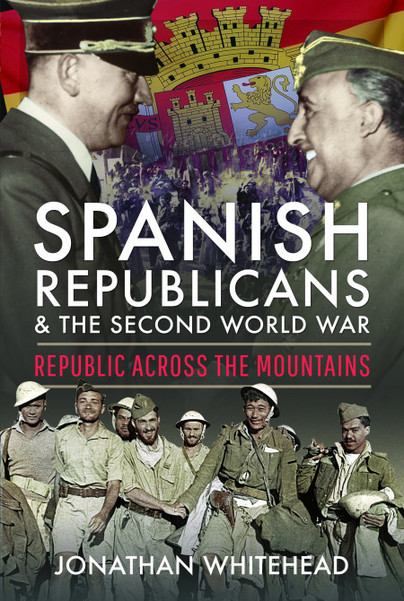

Author Guest Post: Jonathan Whitehead

Republic across the Mountains is the history of the vanquished Spanish Republicans who fled Spain at the end of the Civil War and sought refuge in France. In the first two months of 1939, nearly half a million civilians and troops crossed the Pyrenees to escape the wrath of General Franco’s conquering fascist armies. Unable to cope with the humanitarian disaster, the French authorities detained them in improvised ‘camps’ along the beaches of Roussillon, with no cover from the elements, little food and water, and virtually no medical facilities.

Over the following months, many of the young and old died, many were cajoled into surrendering to the authorities in Spain, the lucky ones were allowed to re-emigrate to Latin America. Those men that remained in France were recruited into the Foreign Legion, or into Work Companies or March Regiments of the French Army. Others found work in agriculture and industry as replacements for the French workforce called up to defend France from imminent invasion. The more politically ‘undesirable’ were held in prison/work camps or deported to North Africa where many would be put to work in slave-camps on the infamous Trans-Sahara railroad.

The German invasion of France in the spring of 1940 added a new dimension to the narrative. For the second time, many Republicans took up arms against the forces of fascism, and over the following five years thousands of Civil War veterans fought in the service of the Allies. They saw action in the Norway campaign of 1940. They fought their way northwards through Africa with Leclerc’s Free French troops and eventually linked up with Montgomery’s Eighth Army. They participated in the Normandy landings and were the first troops into Paris in the summer of 1944 when the Allies and the Resistance liberated the French capital. The handful that remained in Leclerc’s army in 1945 ended their war at Berchtesgaden where they occupied Hitler’s Berghof residence.

Other Republican exiles who remained in France after the military defeat of 1940 played an active role in the Resistance movement and assisted the escape lines that (in collaboration with MI9) were responsible for the rescue of escaping and evading aircrew brought down over mainland Europe. They played a crucial part both in sabotaging the German war-effort, particularly in the weeks before and after D-Day, and in the liberation of many towns in the Midi region. Another less fortunate 8,000 exiles were deported to the Nazi concentration camp at Mauthausen in Austria.

In the early years of the War, a vital element of Churchill’s policy was to ensure Spain remain neutral and to prevent a German attack on Gibraltar. Had the Wehrmacht expelled the British from the colony, the balance of power in the Mediterranean would have swung decisively in favour of the Axis. The Führer made strenuous efforts to persuade Franco to declare war on Britain while Sir Samuel Hoare, the Ambassador in Madrid, and representatives of the Ministry of Economic Warfare worked tirelessly to counter German pressure. At the same time, contingency plans were drawn up in case of a “friendly” or “hostile” German occupation of the Iberian Peninsula. Various Spanish Republicans who had enlisted in the Royal Pioneer Corps after Dunkirk and the Norwegian campaign, were recruited by the SOE and underwent vigorous training in schools and camps throughout England and Scotland in preparation for a guerrilla war. A series of military setbacks for the German Army eventually excluded the likelihood of an assault on Gibraltar and the plans were cancelled.

However, the most significant Spanish contribution to the war effort was made by a single man, Juan Pujol (Garbo), the master double-agent who supplied German intelligence with vast amounts of disinformation, including the nature of the Normandy landings in 1944, and played a critical part in the success of Operation Overlord.

Republic across the Mountains also describes the relations between Franco, Hitler and Mussolini, and the role of the volunteer Blue Division, the 50,000 Spanish recruits who swore an oath of loyalty to the Führer and fought alongside the Wehrmacht on the eastern front during the siege of Leningrad. Those who fought for the French and the British assumed that given the affinity between Franco, the Führer and Il Duce, and the support that the Spanish regime had afforded the Axis throughout the War, the defeat of the Italians and Germans would be followed by the invasion of Spain, the overthrow of the Spanish dictator and the deliverance of a people suffering abject poverty and brutal political and social repression.

In the autumn of 1944, ten thousand Spanish guerrillas, mostly loyal to the Spanish Communist Party, mustered in the Pyrenees to launch the first phase of the liberation of Spain. The title of the book is a reference to an article by Marta Gellhorn, in which the American writer describes the determination of the exiles in France to restore the Republic on the other side of the great mountain range. After a series of cross-border raids they launched their main offensive into the Valley of Aran (Catalonia) on 19 October 1944. The plan was to occupy an isolated area of territory, with difficult access from the Spanish side, and hold it over the winter months as a bridgehead. Having established Republican authorities in the Valley, the guerrillas hoped to trigger a popular uprising which in turn would force the hands of the Allies and compel them to intervene.

The guerrilla army failed to achieve its objectives and within days retreated back across the border into France before Franco’s army could encircle them. This was the final defeat; in a sense, the last battle of the Spanish Civil War. Finally, the book explores the reasons why the Allies chose not to intervene in Spain to overthrow Hitler’s last substantial ally in Europe, and to liberate a people suffering the effects of a ruthless dictatorship that would rule the country until Franco’s death in 1975 – thirty years after the military defeat of fascism in Europe.

Spanish Republics and the Second World War is available to order here.