On This Day: 75th anniversary of the V1 attack on the Guards’ Chapel

Today on the Pen and Sword blog we have a guest post from Jan Gore, author of Send More Shrouds: the V1 attack on the Guards’ Chapel 1944.

For many of us, 6 June

1944 is primarily remembered as the date of D-Day. This year marks

the 75th anniversary of the Normandy landings. What is

perhaps less well-known is the “Doodlebug Summer” that followed

soon afterwards and brought the war, yet again, to the Home Front.

Barely a week after

D-Day, what were known as “pilotless planes” began to appear over

London and the South East. They were a precursor of the cruise

missile, a new type of bomb. The V1 rocket (or “doodlebug”) could

be launched across the Channel from a mobile site in Europe. They

were sent on a pre-set course and programmed to explode (with greater

or lesser accuracy) in London. The advantage to the Germans was that

the new weapons were unmanned and so could be launched day or night;

when they ran out of fuel the engine would stop and they would dive

to the ground and explode. The engine had a distinctive sound, like a

motorbike. When the engine stopped, there was silence, followed

within about 15 seconds by an explosion. With conventional air raids,

people usually had perhaps 5-10 minutes to seek shelter after the

alert. With a V1, you had literally seconds to take cover, and there

was no alert; they were a remarkably unpleasant weapon.

On Sunday 18 June, the

V1s began to reach Westminster. There was a special service at the

Guards’ Chapel that Sunday in honour of Waterloo Day and many

Guardsmen and their families were there. However, it was also an

unofficial thanksgiving for the recent success of the Normandy

landings. The tide of war was turning; mothers, wives and daughters

had all come to the Chapel to pray for their loved ones fighting

overseas. The music at the Chapel was well-renowned and that day

the Coldstream Guards’ Band were playing. There were about 300

people, military and civilian, in the congregation. They included an

American Colonel, an Australian padre, Stanley Baldwin’s son-in-law

and the sister of the painter Edward Le Bas, as well as a large

number of Guardsmen.

The service began at 11

am. Outside, the Scots Guards were drilling on the Square. Lord

Edward Hay began to read the first lesson. As he continued, a distant

buzzing could be heard. He did not falter, even when it became a roar

overhead. He had just finished the lesson and was walking back to his

seat when the engine cut out. Keith Lewis, a Guardsman from the

choir, described what happened next:

“A large area at the

top half of the South wall collapsed; there was an intensive blue

flash; I saw Lord Hay still standing but at a 45 degree angle…already

dead at this moment; there was a very loud explosion; then some giant

was hammering me all over my back.”

The building collapsed

on the congregation, trapping them under up to twelve feet of rubble.

Many were killed by blast; others were trapped under falling masonry.

It was only the third V1 to hit Westminster. The incident was made

worse because the roof of the Chapel had been reinforced with

concrete earlier in the war.

The guardsmen outside

were swift to help; fortunately none of them had been injured in the

attack. The rescue services were on site in a matter of minutes,

desperately trying to remove the rubble and extricate the casualties.

The rescue effort continued until the following Wednesday; 124

people died, including 50 Guardsmen, and over 141 were injured.

The Coldstream Guards’

Band were playing that day; their Director of Music and five of his

musicians were killed outright, while a further twelve musicians were

badly injured. All of the instruments were damaged beyond repair.

Those who died were a

microcosm of society, and my book gives their biographies in full.

They included a pioneering pharmacist, Olive Crooke, who had run a

pharmacy in a military hospital in France in World War One; she had

gone on to support her doctor brother in New Zealand and had returned

to England just two months before because she wanted to help with the

war effort. One of the Coldstream Guardsmen, Tony Titcombe, had hoped

to spend the day with his family; it was his wedding anniversary and

his son’s birthday. He had been taken captive at Tobruk in 1942 and

had been sent to Italy as a PoW; he managed to escape later and

walked to freedom, arriving home for Christmas 1943.

This book describes the

attack on the Guards’ Chapel and gives detailed accounts of the

victims; it also covers the rescue effort and the aftermath of the

attack, and goes on to cover the rebuilding of the Chapel and the

70th anniversary service in 2014.The wealth of

biographical information helps to provide a picture of society at the

time. The historical background to the development of the V1 rocket

helps to explain how and why the campaign evolved; it also describes

other key V1 incidents that summer and draws on first-hand accounts,

including that of my mother. Her statement: “My friends went to the

Guards’ Chapel and they never came back” is what prompted me to

write this book.

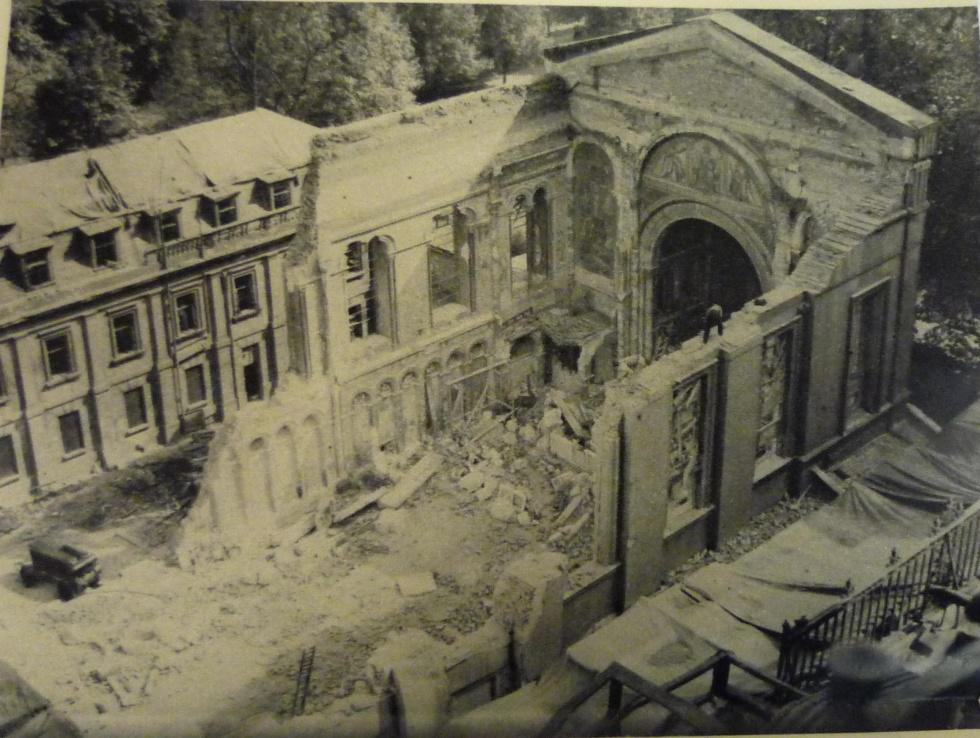

The

Guards’ Chapel after the bombing

Photographs of the

Chapel after the bombing, taken by David Gurney, a young officer

present at the scene.

This shows how a V1 rocket works (from Flickr)

Send More Shrouds: the V1 attack on the Guards’ Chapel is available to order from Pen & Sword now.