Guest Post: David Charlwood

How Boris’ idol Churchill faced down pneumonia

When Britain’s Boris Johnson became the first world leader to be hospitalised with the coronavirus sweeping the globe, an unknown well-wisher placed a message of support on the statue of Winston Churchill that stands in Parliament Square. It was no coincidence. The British Prime Minister is the author of a biography of Churchill and has made no secret of his admiration for the man most regard as Britain’s greatest modern political leader. As Boris struggled with a fever and shortness of breath, he was also going through an experience that would have been all too familiar to his idol Churchill: in 1943, Churchill contracted a debilitating virus that attacked his lungs and nearly killed him.

It started on the plane as Churchill flew back from Tehran, after secretly meeting with US President Franklin Roosevelt and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. The Tehran Conference was the first time the three men had met together and it was a sobering experience for Churchill, as he realised that it would be the dominant powers of the United States and the Soviet Union that would shape the new world order when the Second World War ended; he later confided in a friend, ‘When I was at Tehran, I realised for the first time what a very small country this [Britain] is. On the one hand the big Russian bear with its paws outstretched – on the other the great American elephant.’ He left to fly back to Britain via North Africa, but by the time his plane arrived outside of Tunis, he was already ill.

Tunisian air traffic control had mistakenly diverted the aircraft to the wrong airfield and Churchill got out of the Avro York and sat on his suitcase while they spent an hour on the ground at the wrong location. General Brooke, who was on the flight, later wrote, ‘They took him out of the plane and he sat on his suitcase in the cold morning wind … he was chilled through.’ When they finally arrived at their destination, Churchill was bundled off to bed at the villa he was staying in, while his concerned doctor slept just down the corridor.

The following day, Sunday 12 December, Churchill pottered into his doctor’s bedroom in a dressing gown complaining of a headache and pain in his throat. He was running a temperature of 101°F. Churchill thought he had just caught a chill from the draughty plane, but his doctor was gravely concerned, stating, ‘We have nothing here in this God-forsaken spot – no nurses, no milk, not even a chemist.’ Churchill’s pulse was ‘shabby’ and while his physician could not stop Churchill from working, he requested medical support from an American hospital in Tunis. Another doctor and nurses arrived the following day, with a loaned x-ray machine and electro-cardiograph. A weak and drowsy Churchill messaged his Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, who was back in London, ‘I am caught amid these ancient ruins with a temperature and must wait until I am normal. Future movements uncertain.’ It was worse than a temperature. An x-ray revealed Churchill had pneumonia. An unknown virus was triggering inflammation in his lungs that was gradually making it harder and harder for him to breathe.

Four days after falling ill, Churchill dispatched a cheery message to President Roosevelt from his sickbed. It read, ‘stranded … with a fever which has ripened into pneumonia.’ The same day, 15 December, was the day his illness turned gravely serious. His heart rate sped up considerably, with Churchill telling his doctor it ‘is doing something funny – it feels to be bumping all over the place.’ His doctors prescribed antibiotics and a drug to reduce his heart rate, but were left with no option but to wait it out. The indefatigable wartime leader was finally also worried for himself. As one of his doctors left the room Churchill asked him, ‘I am dying am I not?’ The reply was blunt, but positive. ‘No sir, you are not. I thought you were, but you are on the way up.’

Back in London, Churchill’s absence had not gone unnoticed. Clement Attlee, deputising for Churchill in the House of Commons, had to field repeated requests for a statement on the whereabouts of the Prime Minister, and he finally caved and informed the MPs, and the British public, that the Prime Minister had been in bed with a cold and had developed ‘a patch of pneumonia’. Further proof of the seriousness of the situation came when Churchill’s wife Clementine was bundled onto a plane to Tunis, so she could be by her husband’s bedside. By the time she arrived, however, he was over the worst. He had had no idea she was flying out.

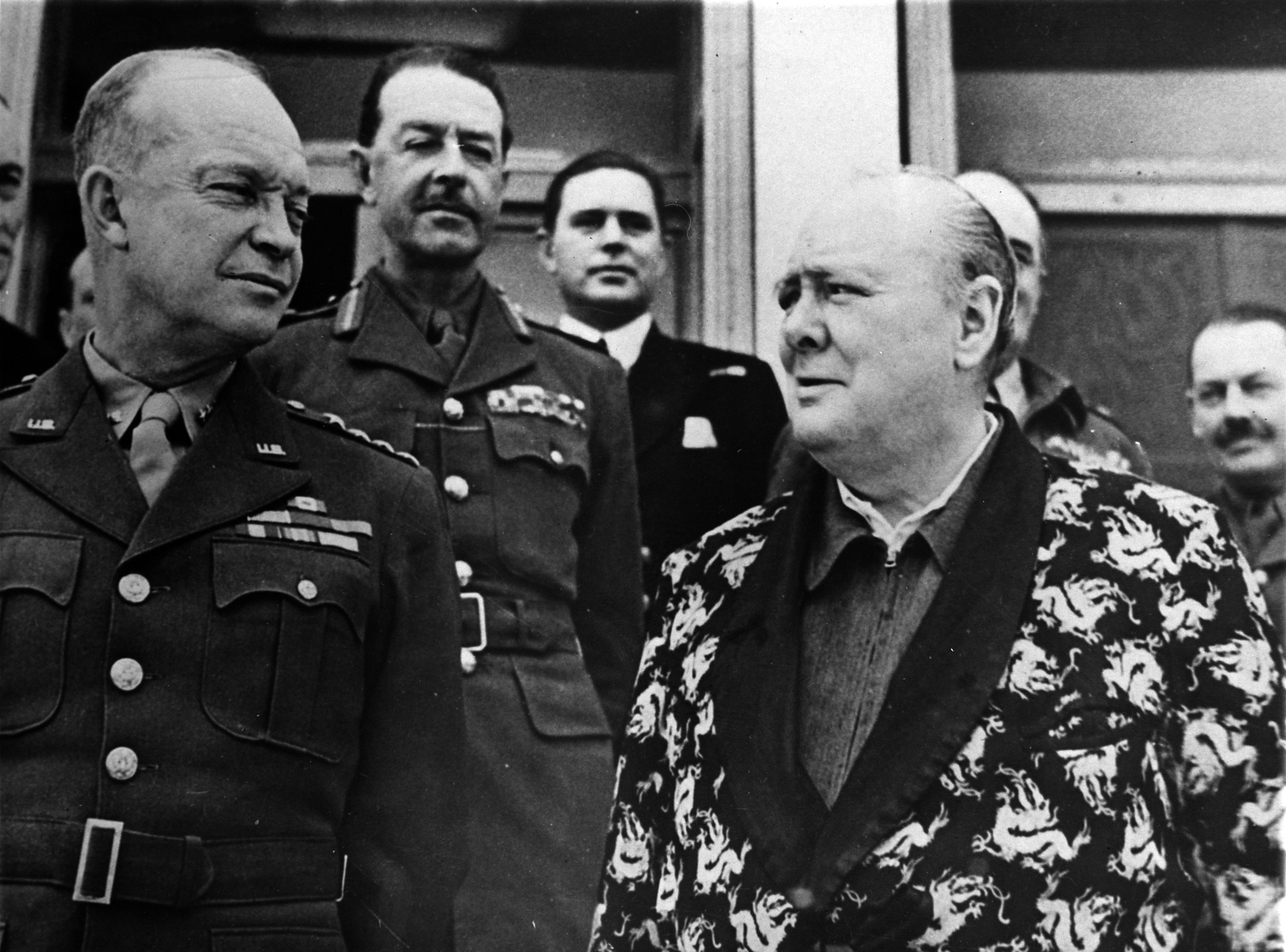

Churchill forever made light of his battle with pneumonia in late 1943, but without the concerted effort that was made to get the necessary drugs and medical equipment, he might well have not survived the combination of pneumonia and repeated attacks of atrial fibrillation. Nearly two weeks after first falling ill he was up and about. It was Christmas Day and Churchill held conference with the American general Dwight D. Eisenhower about the planned Allied landings in Italy. Churchill was still not fully recovered but carried on anyway, spending the whole day wearing a dressing gown. The Prime Minister’s private secretary rather exasperatedly admitted, ‘The doctors are quite unable to control him, and cigars etc have now returned.’

It was a fortnight-long struggle, but with determination and character, Churchill faced down pneumonia. May the current British Prime Minister do the same.

David Charlwood is the author of Churchill and Eden, published by Pen & Sword

Preorder your copy here.