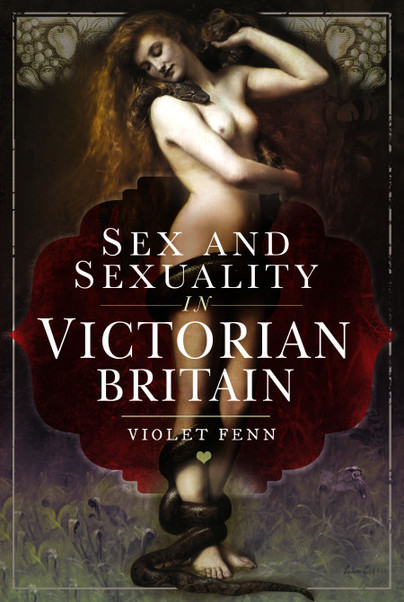

Guest Post: Violet Fenn

FIVE THINGS YOU THINK YOU KNOW ABOUT THE VICTORIANS BUT ARE ACTUALLY WRONG

The Victorians didn’t cover up furniture in case it was ‘too sexy’

It is often said that the nineteenth century was such a prudish time that people were concerned that even such innocuous items as the bare wooden legs of tables and chairs might be too titillating for polite company. It’s said that pianos would be covered with fabric in order to avoid any accidental furniture-related excitement, should a gentleman accidentally cast his eyes on its curvaceous undercarriage.

This theory quite possible has as its origins a practical joke that was played on English traveller Frederick Marryat, during his travels in America in 1837. Marryat visited a seminary for young ladies in Niagara Falls, where he was astonished to discover the piano legs sheathed in what he later described as ‘modest little trousers’. These coverings, a local guide confided, were necessary to preserve the ‘utmost purity of ideas’ amongst the impressionable young girls.

On another occasion, a young girl told Marryat that even saying the word ‘leg’ was considered too risqué in America; ‘limb’ was preferred at a pinch. Captain Marryat dutifully recorded all of this in his book A Diary in America, which was published in 1839.

There are no other records of this conservative habit; possibly the piano legs were covered at the seminary, but if so, it’s more likely that it was done to protect furniture from dust or accidental scuffs.

Prank or not, the tale that Marryat recounted in his book could perhaps have been believed and acted upon by fashionable households back in Britain who didn’t want to appear to be behind the times.

Queen Victoria was anything but a prude

Quite the contrary – Britain’s young Queen was utterly unafraid of admitting to her appreciation of the physical side of married life, writing endless diary entries describing her love both for her Prince and also for their active sex life. Remembering her wedding night, Victoria wrote, “It was a gratifying and bewildering experience. I never, never spent such an evening. His excessive love and affection gave me feelings of heavenly love and happiness. He clasped me in his arms and we kissed each other again and again.”

Victoria’s eagerness to make the most of private time with her husband led to suggestions that she sometimes wore him out with her constant physical cravings. She was certainly ardent in her affections – the portrait of the Queen painted by Franz Xaver Winterhalter in 1843 that is commonly known as ‘The Secret Picture’ was commissioned by Victoria herself as a gift to her husband. The seductiveness of the pose portrayed by Winterhalter was considered incredibly risqué for the time and could be interpreted as the nineteenth century equivalent of sending one’s partner sexy phone pics.

Doctors didn’t cure ‘hysteria’ with mechanical vibrators

Contemporary images of rather intimidating looking mechanical vibrators are often used as ‘proof’ that doctors would masturbate female patients to orgasm in order to release hysterical tension. The thought process behind this is that to have done so manually would have been wearisome on tired medical fingers, and so machines were brought in to lighten the workload.

Although no one cannot be sure that these gadgets were never used for such an interesting purpose in private, the vast majority of such inventions were, in reality, intended to massage aching back or neck muscles. If you’ve ever seen one of these devices in real life (I was lucky enough to find one on a flea market stall a few years ago and it now sits proudly on the desk in front of me), you’ll know that there is nothing about them that would tempt you to apply it to any bodily part more tender than perhaps a particularly sturdy shoulder blade.

Prince Albert probably didn’t have a Prince Albert

It has long been suggested that this extreme but popular male piercing is so named because the Queen’s consort himself had such a decoration. Men did sometimes have a ‘dressing ring’ inserted into their penis in order to keep things neat in the trouser region, following a fashion allegedly begun by Beau Brummell. The ring could be hooked to one side and is often said to be the origin of the phrase, ‘Does sir dress to the left or right’, which is so beloved of upmarket tailors.

There has never been any real evidence to support the theory that the Prince Consort was a partaker of the piercer’s needle. It is perhaps more likely that the connection is actually to the royal couple’s grandson, Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale. Notoriously louche, the younger Prince Albert was a regular visitor to brothels and was connected to several society scandals, including several dalliances with chorus girls from popular London theatres.

Of these two potential sources for the legend, the young Duke is a far more likely namesake.

Oscar Wilde didn’t die of syphilis

Despite his death often being assumed to have been caused by syphilis, Oscar Wilde actually died of meningitis caused by an ear infection. Whilst incarcerated in Wandsworth Prison, Wilde collapsed and fell onto the hard floor, rupturing his eardrum in the process. Left without proper treatment, despite Wilde having spent quite some time in the prison infirmary, the ensuing infection left Wilde in pain for the rest of his days.

Wilde’s last words are famously said to have been, “Either that wallpaper goes or I do,” but what he actually said was, “My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One or other of us has to go.” And go Wilde did, dying in a cheap hotel room in Paris, France, on November 30th 1900.

……………………………………………………………………………………….

Discover more in Sex and Sexuality in Victorian Britain. Order a copy here.