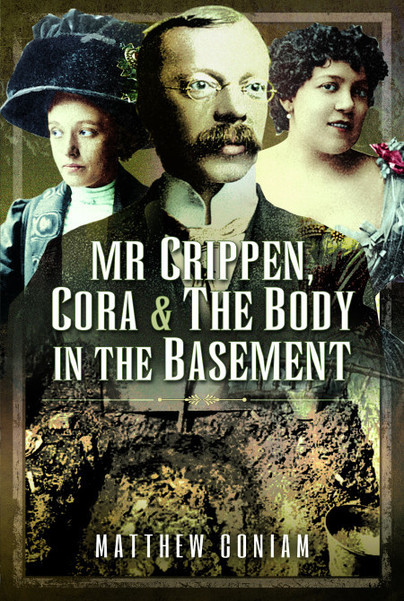

Mr Crippen and the Media Mob

Guest post from author Matthew Coniam.

I first got interested in the Crippen case as a child, and for what I presume to be the usual reasons: because there was something fascinating and eerie about the historical trappings. The big, gloomy house, the basement, the gaslight, the heavy velvet curtains, the frock-coats and waxy moustaches… I saw his waxwork at Madame Tussaud’s and shivered at the thought of him planning ghastly murder in the winter months of 1910, and stashing the evidence in his basement. An especially grim window on an inherently spooky lost age.

But, paradoxically, what made me determined to write about the story, after the DNA discoveries that so transformed what we all thought we knew for certain about it were released in 2007, was my realisation that in one key respect this was, for all that, an incredibly modern story. Indeed, in a sense, one might call it the inaugural chapter of a very modern tragedy, the birth of a phenomenon that, I would argue, claimed Crippen as its symbolic first scalp, and that today, in the age of instantly mobilised internet outrage, is a bigger menace than ever. That phenomenon? Trial by media.

The newspapers had long known that few things guarantee a healthy circulation quite like a gruesome murder story. In particular the Jack the Ripper crimes of 1888, in which Inspector Dew, the man who orchestrated the pursuit and dramatic arrest of Crippen, was peripherally involved, had gripped the world’s media in 1888. But the Crippen case was different, and new, in several important ways. All the ingredients were there, of course. Crippen’s wife had disappeared, and her friends did not believe his claim that she had gone to America, sickened and died. The police investigate, and find Crippen living with his young secretary as man and wife. Crippen now claims that he had lied about his wife’s death: the truth is that she left him and as far he knows she is still alive. Then, he and his mistress flee the country by sea, she with her hair cut short and in disguise as his son. The police search Crippen’s house and find a mass of mangled human flesh, shallowly buried under the bricks of his coal cellar, and the hunt for the fugitives begins… But Dew, who had felt the police had bungled in keeping the press at resentful arm’s length during the Ripper enquiry was determined to recruit the fourth estate as willing allies this time. As such, he gave them unusual access to the developing case, the findings, and above all to the details of the pursuit, as he raced to Canada on a faster vessel, intent on apprehending the pair at the moment of their arrival.

To the reading public, it was irresistible. Here was a dramatic true life murder mystery unfolding in real time. With breathless excitement they followed each detail of the discovery, the hunt for the missing suspects, and then, once the pair had been spotted, the race to capture them. Every morning brought some new revelation about the grisly find in the cellar and, thanks to the wonder of wireless telegraphy, a daily update on the nail-biting pursuit. It was the first time the public had so much inside detail on a developing police enquiry, to which they were given what must have seemed uniquely privileged and sustained access. Combine that with the story’s irresistible drama – the horror in the cellar, the fugitives fleeing in disguise, the tense race across the seas – and the result was a sensation.

But there was, of course, a big downside to all of this. The lines between a sober police investigation and a thrilling serial romance had been hopelessly and dangerously blurred. Because Crippen had from the very beginning been cast as a melodrama villain of the deepest dye, his guilt had in a very real sense been already determined. By the time of the second-act climax, with Dew making his arrest and bringing his man back to London, the trial had come to seem like a mere formality. Indeed, on the very day it began, the remains from the cellar were buried in St Pancras Cemetery, where they remain, under a headstone baring the name of Cora Crippen. Yet the question of whether they were hers or not was the very thing the trial was supposedly yet to determine.

In truth, as I make clear in my book, the case against Crippen was technically not strong, and sprinkled throughout with helpful circumstantial evidence that is now more than ever disturbingly suggestive of foul play. But reading the trial transcripts yields an even bigger surprise, one that just about every previous study has managed to obscure by the simple expedient of omission. Not merely was the prosecution’s case surprisingly feeble, but it was met confidently and consistently by rebuttal evidence from the defence, offered by experts every bit as qualified and every bit as certain in their convictions as those lined up by Crippen’s accusers. You’d simply never know this from reading the standard Crippen literature, which focuses on the defence only superficially, noting the occasions when the prosecution was able to score points against it, but rarely if ever acknowledging the detail and cogency with which the likes of Dr Gilbert Turnbull and Dr Reginald Wall made, explained and stuck to entirely different conclusions to those advanced by the prosecution experts. Turnbull in particular emerges from the unglossed story a very different man from the one painted in the orthodox accounts as a shallow dissembler, with a petty grudge against prosecution superstar Bernard Spilsbury, who was tricked into giving a petulantly contrary view on the assurance that he would not be called at the trial, then was, and was forced to stick by it spuriously in the witness box. Re-read what actually went on, and this is revealed as nonsense. Turnbull was sincerely and unwaveringly convinced that the so-called scar on the mortal remains was merely a fold in the skin, an opinion that he patiently and convincingly accounted for, that he stuck to throughout the proceedings, that he was still asserting some seven years later, and in which, it now seems, he has been entirely vindicated.

Yet for some reason the jury chose not to be troubled by any of this, and the defence experts seem to have passed across the bleak proscenium almost literally unnoticed by them. They went into the trial with their predetermined narrative, listened for it from the prosecution and, like the waiting world, seem never to have allowed even a flicker of doubt – doubt that an accused man is entitled to the benefit of in British law – to jerk them from its pre-scored groove. For Crippen to be innocent would not just mean that the great engine of British justice had been set so expensively, publicly and vengefully on the wrong course. Something much more important than a few red faces in the British establishment was at stake. If Crippen was innocent, then all that wonderful drama, all that excitement, all that romance and tragedy and heroism, was all for naught. There is a term for this: it is anti-climax. And the Crippen narrative could never, ever end in anti-climax: that was unthinkable. A last act fully worthy of its first and second was simply essential, as unquestioned as it was unquestionable.

We now know that the case against Crippen was, in fact, fatally flawed from the start. The medical evidence on which the prosecution relied was just plain wrong. Some of the secondary physical evidence now looks to have been planted. And DNA tests have proved conclusively that the remains in the cellar were not those of Cora Crippen. In fact, they were not even female. Whoever they belonged to, we know of no reason why Crippen might have put them there, and nothing whatever linking him to the crime of which he was accused – a murder that may very well have never taken place, certainly for which there is absolutely no evidence at all.

But that Big Narrative, settled and cemented in the media of the world long before Crippen stepped into the dock, won the day regardless. It was the media’s narrative that tried and condemned him, and it was the media’s narrative that, on a cold November morning in 1910, tied a rope around his throat and sent him plunging into oblivion.

You can order a copy of Mr Crippen, Cora & the Body in the Basement here.