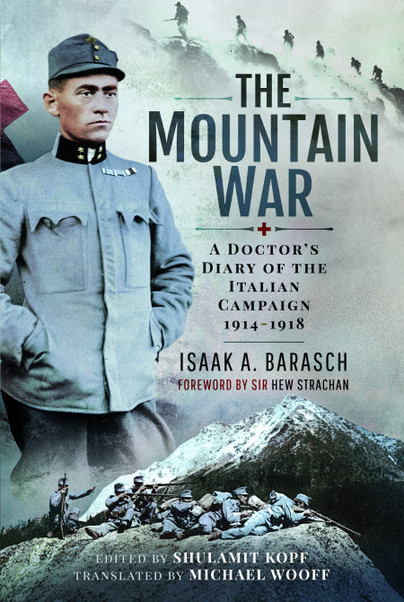

The Mountain War

Author guest post from Shulamit Kopf.

Call it an amazing coincidence.

Important 105-years-old photographs landed at my doorstep this week; five months too late to be published.

Attached with glue to the black pages of a photo album that had come apart, they slumbered undisturbed in a drawer some 50 years. When their owner died, they were transferred to an old suitcase that got moldy over 50 more.

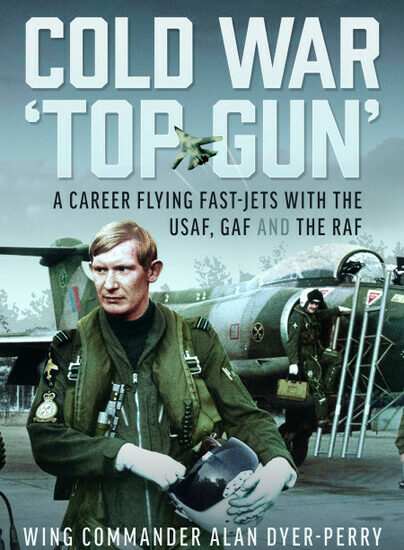

What are the odds that the photos, undisturbed for more than 100 years, would turn up two days after I receive in the mail a hardback copy of the book I had published, The Mountain War, A Doctor’s Diary of the Italian Campaign 1914-1918, by Isaak A. Barasch?

Dr. Barasch, my great uncle, mentioned several times in his WWI diaries that he had a camera and had taken photos. He served as a doctor in the Austro- Hungarian army on the Italian front.

He died of the Spanish Flu in 1918 just months before the end of the war, and one of his sisters took his wartime diaries, and now as it turns out, his photos as well, when she immigrated to New York City.

Had one of his other siblings in Poland taken charge of them, my grandmother, for example, they would have gone up in smoke in the next world war.

It took another global flu epidemic to get his diaries published since it was during the first Covid lockdown that I found the time to jumpstart the project.

And now, with another brutal war in Europe, the diaries have become more relevant than ever.

Even as a young adult I knew of the diaries’ existence. I knew his sister, Helen Mehlman, had them in New York City.

After she passed away, I had asked her daughter, Irene, to copy a few pages for me. I was curious to know what my great-uncle wrote. She was already in her 80s when Irene realized I was the only one in the family showing interest and the next time I called, she entrusted them to me. I had them translated from German into English and realized the diaries were a historic treasure of major significance, or, as the translator wrote to me at the time, “your great-uncle deserves to be bequeathed to posterity.”

I’m ashamed to say the translated diaries languished for almost a decade in a drawer. It’s a big project to get them published and who has the time?

That’s exactly what the first Covid-19 lockdown provided.

The book was published by Pen & Sword Books recently with an introduction from one of the world’s renown WWI historians, Sir Hew Strachan of Oxford University.

My great-uncle, Dr. Barasch, mentioned several times in his diary that he had a camera and took various photos. While working on the project I wondered what had happened to them.

A few weeks ago, I received an email from Irene’s daughter who said she had found the old suitcase while clearing out her parents’ apartment.

“Don’t throw anything out,” I said. “Whatever you don’t want send to me.”

And so, the box with dozens of letters in Polish and German, documents and photographs arrived two days after the book, or as Albert Einstein said, coincidence is God’s way of staying anonymous.

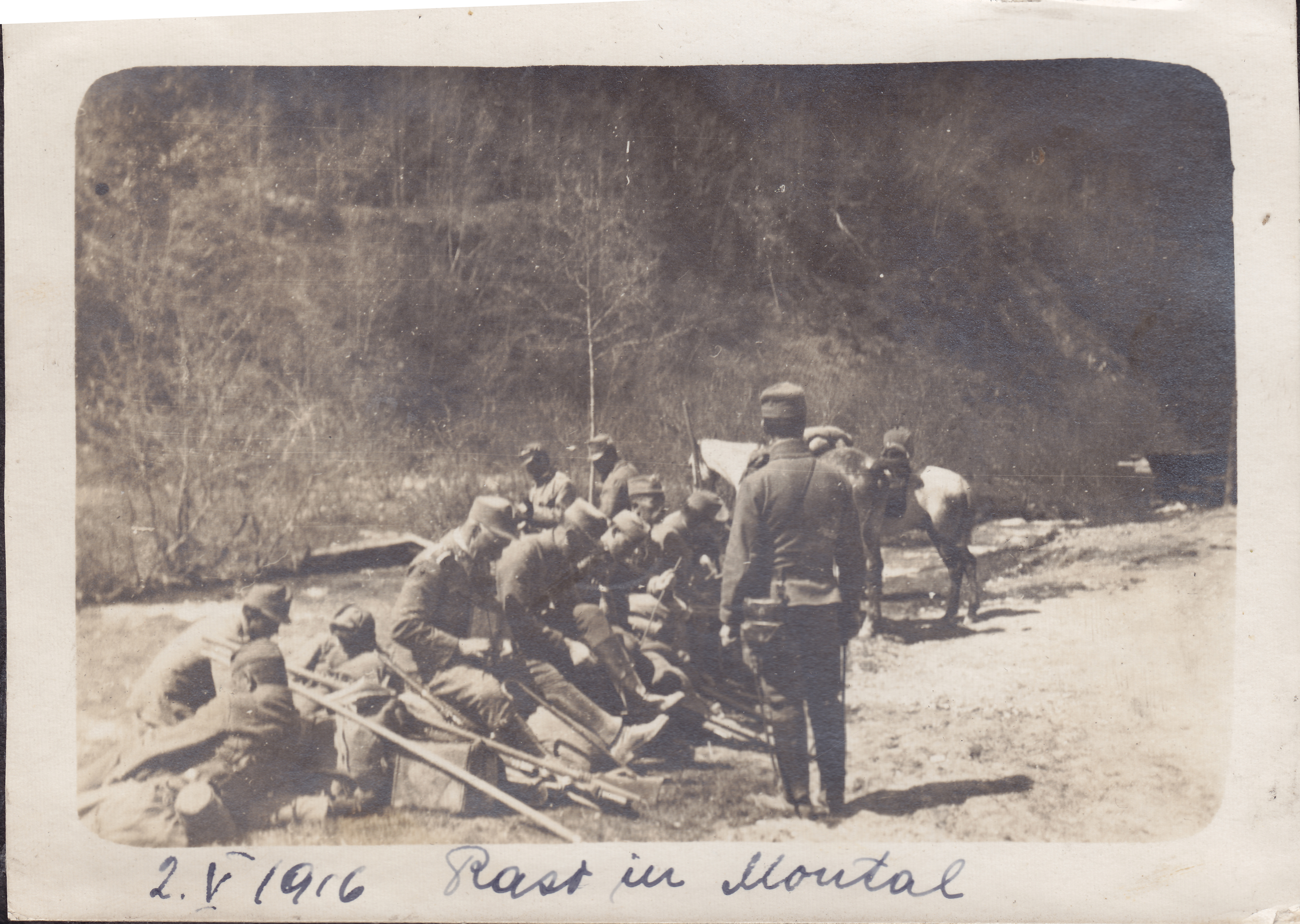

On the bottom of some of the photos my great uncle wrote the name of the place and the date. That made it easy:

2 May 1916

We are on the march from Niedersdorf via Welsberg to Bruneck. We are even having a little rest on the other side of Vercha, a very small locality. This for the second time during our march. The first time we stopped at the Windschirm Guesthouse. Here I took a photograph. The soldiers on the march resting with their officers in the foreground with the Anthalzer valley and the place called Anthalz in the middle ground and the mountains in the background. The weather was most favourable. A cool and calm day. The Rienz accompanies us with its dull and mysterious rushing noise. The birds are singing prettily. The woods are standing there, dumb and blessed in all their splendour. Deep peace reigns both far and near in the valley of the Puster. An untroubled and idyllic picture. We could almost forget all the horror of this dreadful war, all the nastiness and cruelty which is being played out not so far from here, up there in the snow-covered mountains.

Another photo had faded over the years but upon a closer look I was able to see Dr. Barasch standing in front of a group of soldiers, all wearing gas masks on their faces.

February 16, 1916:

“Today I had to go to Valkiscie for distribution of gas mask to each of the men and the officers in the battalion to be worn during enemy gas attacks and which can save your life in such cases. They serve as air filters containing chemicals that bond with poisonous gases (especially chlorine.) I also got two for myself.”

My great uncle was an important witness of the time add his diaries have become prophetic and timeless given the war between Russia and Ukraine.

He was acutely aware of the lunacy of it all. On the second anniversary of World War I he wrote:

“How much longer must this inconclusive struggle between nations go on? There have already been enough victims for mankind to bear, going on for seven million dead just in Europe these last two years. And then there are the imponderable phalanxes of the crippled and sick. Immeasurable treasures gone up in smoke. Poor humanity for putting up with this! How cowardly you are! Where are your high ideals? Where is your love of liberty? Where are your freedom fighters?… You allow yourselves to be enslaved and led astray so easily.”

He would have seen Europeans led astray once again a few decades later had he survived the war and set up his practice in Vienna which is where he earned his medical degree. And now, yet again.

February 14, 1916

“We must be prepared for the worst. Nobody here knows if he might be hit in the space of a minute by one of those highly diverse and cruel lethal weapons. Weapon technology has thought of everything. Trinitrophenol bombs, gas, mine-throwers, mortar of every caliber and every type of machine gun, shrapnel and shells of the most varied kind.”

The only thing that seems to have changed since the day he wrote those words almost exactly 106 years ago is the technology for murder and mayhem.

A tourist Internet site for the Dolomite region boasts of many World War I museums, monuments and cemeteries. My great uncle was there when the graves, row upon row, were freshly dug, must have known some of the dead — comrades, patients.

“New graves are appearing daily… Everything all over this region speaks eloquently of the bloody, violent, countless struggles, battles, attacks and counterattacks, all the killing, anger and destruction,” he wrote.

When this conflict in Ukraine ends, there will be new graves dug, new monuments erected to the heroes.

Dr. Barasch wrote something that should be inscribed on all the grand marble war memorials the world over:

“The guns should be silent for once. Mankind needs a rest.”

The Mountain War is available to order here.