World Book Day – Natalie Grueninger

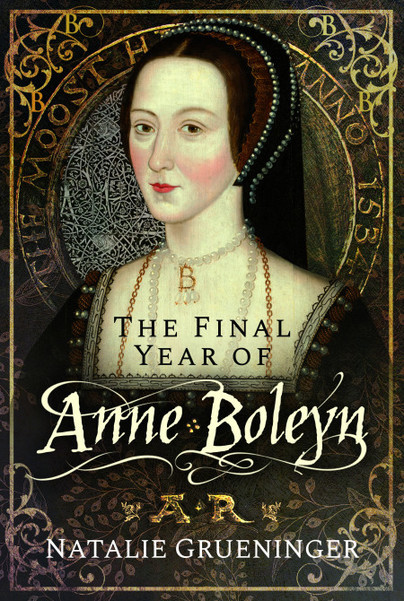

In this post for World Book Day, Natalie Grueninger explains the writing process behind her recent release The Final Year of Anne Boleyn.

What inspired you to write your book?

Since 2009, I have dedicated countless hours and a great deal of energy to studying and researching the life and times of Queen Anne Boleyn. While immersing myself in Anne’s extraordinary story, I read many differing accounts of her downfall, but they all had one thing in common. They chiefly focussed on the last six months of Anne’s life and attempted to make sense of her shocking fall by solely looking at the events of 1536.

I felt, however, that if we wanted to truly understand how a life that started with such promise ended in a pool of blood on a scaffold at the Tower of London, we needed to cast the net wider and closely examine the year 1535 as well. Among other things, this telling period bore witness to one of the most politically significantly progresses of Henry VIII’s reign and a renewed sense of intimacy between the royal couple. It was, though, also a time of mounting pressures, and serious threats loomed at home and abroad. When these events are scrutinised in conjunction with those of 1536, a much clearer pictures emerges of why Anne ultimately died.

I was also greatly inspired by my desire to examine, wherever possible, the evidence myself, rather than rely on second-hand interpretations. It was a daunting task, but one that proved especially rewarding in the end, as it brought me much closer to the woman behind the tantalising tale.

What interesting facts have you uncovered during your research?

Many! Here are just a few of examples. In August 1535, Queen Anne Boleyn wrote to her sister-in-law, Margaret, the former Queen of Scotland and Henry’s elder sister. Accompanying the king and queen’s letters were fine gifts, including £200 and a selection of splendid fabrics, including cloth of gold and silver, crimson and purple satin, and black velvet. Anne also sent Margaret a piece of cloth of tissue from her own wardrobe, as a mark of her sisterly affection.

I also discovered that the same month while the couple were lodged at Thornbury Castle in Gloucestershire, they were joined by Margaret Erskine, who was reputedly James V’s favourite mistress and the mother of the king’s illegitimate son, James Stewart, the future Earl of Moray. Sadly, there’s no record of what went on during the visit. Considering that Anne had been Henry’s mistress before her marriage, it’s interesting to wonder whether she would have welcomed Margaret or resented the reminder of her former position.

I also came across a letter penned by Anne to Thomas Cromwell that offers us a rare glimpse into what Anne might have actually sounded like. As there was no standardised spelling at the time, people spelled phonetically, which provides a window into pronunciation. For example, Anne spells the word ‘obligation’ as ‘hoblygassion’, suggesting that the queen may have spoken with a faint but recognisable French lilt.

What was the hardest part about writing this book?

It was most definitely sifting through the thick layers of myth and legend to try to uncover lost gems of truth. The fragmentary and contradictory sources in some cases and the complete lack of sources in others, also proved challenging. On a more personal level, it was incredibly taxing to write about the judicial murder of six innocent people. Like Elizabeth and Thomas Boleyn, I’m the parent of a spirited son and daughter, and the thought of losing them in such horrific circumstances, and of being powerless to save them, is utterly unbearable. It’s little wonder that by mid-March 1539, both Elizabeth and Thomas had followed their children to their graves. The injustice and brutality literally shattered their hearts.

Is there a unique angle to this book and if so, what is it?

Yes, I think there is. It’s the most comprehensive account of the final 18 months of Anne Boleyn’s life. I go into a great deal of detail, very carefully assess the sources and ultimately offer a fresh interpretation of these well-known events. I also challenge a number of longstanding myths!

What has researching this book taught you?

It has taught me to always keep an open mind and to continually question longstanding beliefs. Just because it’s written in countless history books, doesn’t mean it’s true! This journey has also emphasised the importance of challenging myself by welcoming differing perspectives, even if it feels uncomfortable at first. I also learnt to trust myself and to value the knowledge that I’ve gained over the last 14 years of research.

What part of the book are you most proud of?

That’s a difficult question to answer. I think I’m most proud of the parts in which we get a real sense of the whole woman behind the famous name – not just Anne the queen, but Anne the mother, sister, daughter and friend. My favourite moments are those when she emerges from the pages and stands three-dimensional before us, a brilliant, courageous and complex human being.

Order your copy here.