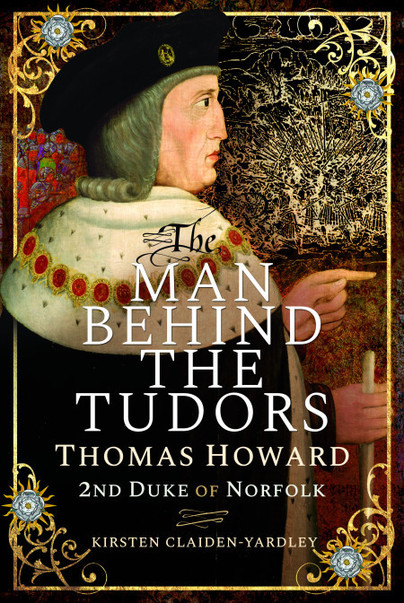

Top Ten Tudor Love Stories: Part 2

We hope you enjoy the first part of Kirsten Claiden-Yardley‘s countdown of the top ten Tudor love stories! Here’s the top five – oh la la!

5 – Elizabeth I and Robert Dudley

The marriage of a monarch was always a serious matter with major diplomatic implications. This was amplified when the monarch was female. In Tudor England, women were not seen as mentally or physically capable of exercising the same authority as a man, and a husband was expected to rule his wife. A husband for Elizabeth was desirable to ensure an heir and to provide male support for her, but equally it had to be the right man to ensure England’s interests and independence were protected. The question of Elizabeth’s marriage lasted twenty-three years, and was never resolved.

Whilst she may not have married that does not mean that Elizabeth never fell in love and many rumours circulated about her relationships with male courtiers. The most famous of these was Robert Dudley, earl of Leicester, although there is as much obsession and tragedy to the story as there is love. Elizabeth’s love and affection for Robert was widely known and was even an obstacle in arranging a marriage with a foreign suitor. It is likely she would have married him if she could but there were deemed to be too many objections to the match, not least the unexplained death of his first wife. Instead, she showered him with gifts of titles, lands, and political offices in order to keep his loyalty and devotion. Even when she suggested that Robert marry Mary, Queen of Scots she proposed that the newly married couple live at her royal court so that she could keep Robert nearby.

Elizabeth’s unwillingness to either marry him or let him go, drove Robert to frustration and he described himself as ‘tied in more than unequal and unreasonable bonds’. He began to have affairs with female courtiers and then, in 1578, he married Lettice Knollys. Elizabeth never forgave Lettice for stealing Robert. When Elizabeth died, a bundle of Robert’s letters to her was found amongst her personal possessions.

4 – Mary Tudor and Charles Brandon

The younger sister of Henry VIII, Mary was sent to France in October 1514 to marry King Louis XII, a man thirty-four years her senior. By January 1515, she was a widow. Her brother’s childhood friend and closest companion, Charles Brandon, was charged with safeguarding Mary in England’s interests. An attraction already existed between the pair and Henry VIII had promised that, after a seemly interval, they could marry. However, Mary feared that either brother or her step-son, King Francis I, would instead marry her off to someone else for political gain. Desperate to marry Charles, Mary persuaded him to go through with a secret ceremony whilst they were still in France.

Their deception provoked an outpouring of fury from Henry VIII, fuelled by Charles’ rivals at the royal court. After many letters begging for forgiveness, and success in securing Mary an ongoing income from the lands she had been given in France, Henry relented and attended their public wedding on 13th May 1515. However, forgiveness came at a high cost. Mary was required to pay her brother £2000 a year for the next 12 years – an eyewatering amount at that time. They also spent some months in self-imposed retirement at their country estates in Suffolk; although Charles eventually returned to the royal court, Mary rarely returned to her former life at court.

3 – Thomas Howard and Mary Douglas

The fall of Anne Boleyn in 1536 had far reaching implications and amongst the victims of the aftermath were Anne’s uncle Thomas and Henry VIII’s niece, Mary Douglas. Thomas was a son of Thomas Howard, 2nd duke of Norfolk by his second wife, and he had been a regular attendee at the royal court since 1533. It was there that he met and fell deeply in love with Mary, the daughter of Henry VIII’s sister, Margaret, by her second husband. Amorous poems composed during their relationship have been preserved in the British Library and, in 1536, they secretly promised to marry.

Unfortunately for the young couple, after Anne Boleyn’s execution both Henry VIII’s daughters were declared illegitimate. Mary therefore became heiress presumptive to the English throne. When Henry found out about their secret contract to marry, he accused Thomas of trying to seize the throne via a royal bride and imprisoned them both in the Tower of London. Mary was given into the care of the Abbey of Sion after falling ill and remained there until she was released on 29 October 1537. Thomas died in the Tower two days later.

2 – Thomas Cranmer and Margaret

During 1532, Thomas travelled to Nuremburg to gain support for Henry VIII’s divorce. Whilst there, he met and married Margaret, the niece by marriage of Lutheran preacher, Andreas Osiander. Now that he was an ordained priest, the risks he took in marrying again were even higher than they had been when he married Joan. Margaret and their children spent much of their time hidden in England, relying on the loyalty of friends to keep them safe, or in exile in Germany. Only during Edward VI’s reign were they able to live openly as husband and wife. During Mary I’s reign, Thomas was convicted of treason and executed on 21 March 1556.

Evidence of Thomas and Margaret’s love and happy marriage can be found in the 1549 Book of Common Prayer which Thomas co-wrote and edited. For the first, time the marriage service included the vow to love and cherish each other, and a third reason for marriage was added: “the mutuall societie, helpe and coumfort, that the one oughte to have of thother, both in prosperitie and adversitie”.

1 – Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn

Possibly the most famous Tudor love story and one which irrevocably altered England’s religious, social, economic and political landscape. Anne first caught Henry VIII’s eye in 1526, nearly five years after she arrived at the English royal court. The strength of Henry’s feelings for Anne are evident in the seventeen love letters sent by him between 1527 and 1528. Despite his protestations of love, Anne refused to be Henry’s mistress. By spring 1527, Henry no longer had a physical relationship with his wife, Katherine of Aragon, and was desperate for a male heir. He reached the conclusion that his marriage had never been valid and should be annulled. However, rather than seeking another foreign bridge, he made the surprising decision to propose marriage to Anne.

It was not to be an easy path to marriage for Henry and Anne. The pope had no desire to offend Katherine of Aragon’s powerful nephew, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, by agreeing to the annulment. It took five years, the fall of Cardinal Wolsey, the rise of Thomas Cranmer, and the severing of the church in England from papal power in Rome to secure a divorce for Henry. Determined that any child they might have should be legitimate, Anne and Henry remained abstinent until November 1532 and they finally married in January 1533. Anne became only the second Queen to be drawn from the English nobility since 1066, and the way was paved for the dissolution of the monasteries and the eventual creation of a Protestant church of England.

Their early passion and devotion were not sufficient to secure a happy ending for Henry and Anne. In contrast to Katherine, Anne was not a popular Queen and had many enemies. Then the birth of a daughter followed by two miscarriages aroused Henry VIII’s fear that, as with Katherine of Aragon, God was punishing him for an invalid marriage. In the end, it was Anne’s former ally, Thomas Cromwell, who, after she obstructed some of his plans, used Henry’s doubts and the flirtatious nature of Anne’s court to bring about her fall. Anne and several of her courtiers, including her brother, were tried for treason on the grounds of adultery. Whilst it is generally accepted that the charges were false, they were found guilty and executed. Anne went to her death still hoping for a last minute reprieve from her husband.

The Man Behind the Tudors is available to order now from Pen and Sword.