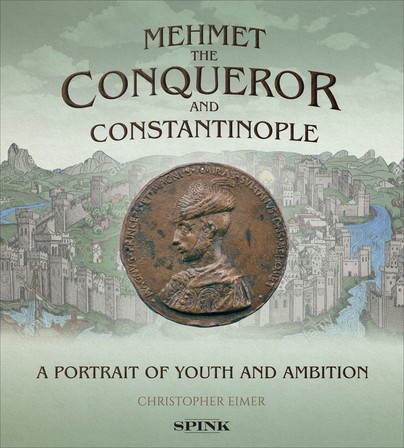

Mehmet the Conqueror and Constantinople (Hardback)

A Portrait of Youth and Ambition

By

Christopher Eimer

Imprint: Spink Collectables

Pages: 64

ISBN: 9781912667666

Published: 15th March 2022

Imprint: Spink Collectables

Pages: 64

ISBN: 9781912667666

Published: 15th March 2022

You'll be £25.00 closer to your next £10.00 credit when you purchase Mehmet the Conqueror and Constantinople. What's this?

+£4.99 UK Delivery or free UK delivery if order is over £40

(click here for international delivery rates)

Need a currency converter? Check XE.com for live rates

(click here for international delivery rates)

Need a currency converter? Check XE.com for live rates

In its significance for both Islam and Christianity, and ultimately the wider world, the fall of Constantinople on 29 May 1453 was to herald the dawn of the early modern period and bring universal recognition to the man forever known as Mehmet the Conqueror, or Sultan Mehmet II (1432-1481); who at the age of twenty-one had brought the millennium-old Byzantine empire to an end.

The very improbability of such an accomplishment, after many failed attempts on Constantinople by different factions over the centuries, was to only add to Mehmet’s growing status; while his quest for territorial acquisition over the following twenty-five years, in the establishment of an Ottoman empire, was to place this dynastic family on the international stage, where they would remain a significant political force over the following five centuries.

Little material evidence has survived from the formative period of Mehmet's life, and certainly nothing of any direct significance such as a portrait. However, Mehmet had an enduring interest in that genre, though it was naturally assumed that after an absence of more than five centuries a portrait of the young sultan in any form had simply not survived the intervening period.

The appearance of a circular portrait relief of the sultan was thus to be of more than passing interest, given the youthfulness of the turbaned Muslim sitter, who was immediately identifiable as Mehmet the Conqueror from both his modelled bronze relief profile and the titles encircling his portrait, addressing its subject in Latin as the 'Great Prince and Great Emir, Sultan Master Mehmet' - Magnus Princeps et Magnus Amiras Sultanus DNS [= Dominus] Mehomet.

The willingness of Mehmet to commit his imperial vision to the hands of a western artist at such an early period of his life is at the heart of this extraordinary episode, which embraces the looming extinction of the millennium-old empire of Byzantium, an expanding Ottoman political enterprise and the fall of Constantinople itself. It represents a fusion between east and west that is without parallel in the mid-fifteenth century.

Indeed, so directly can the commission of the bronze relief be linked with Mehmet that beyond the revelation of his youthful, and enigmatic, portrait is the remarkable sense of an event of historic proportions, now viewable through the eyes of the protagonist himself.

There are no reviews for this book. Register or Login now and you can be the first to post a review!

Other titles in Spink Collectables...