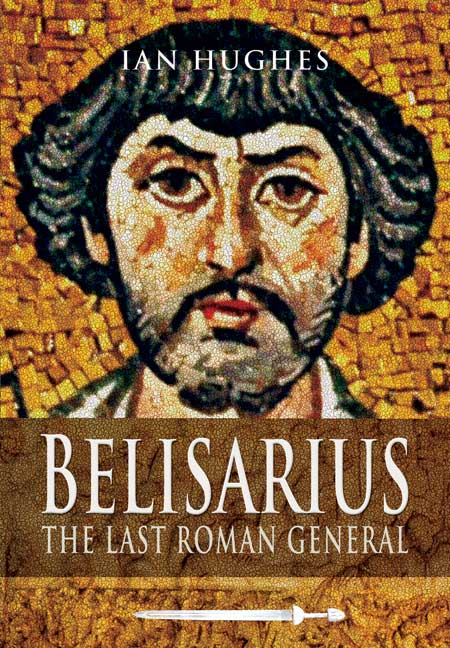

Belisarius (eBook)

The Last Roman General

Imprint: Pen & Sword Military

File Size: 9.1 MB (.epub)

Pages: 224

Illustrations: 15 black and white drawings, 27 maps & 18 battle plans

ISBN: 9781844689415

Published: 15th January 2009

| Other formats available | Price |

|---|---|

| Belisarius Paperback Add to Basket | £16.99 |

A military history of the campaigns of Belisarius, the greatest general of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Emperor Justinian. He twice defeated the Persians and reconquered North Africa from the Vandals in a single year at the age of 29, before going on to regain Spain and Italy, including Rome (briefly), from the barbarians. It discusses the evolution from classical Roman to Byzantine armies and systems of warfare, as well as those of their chief enemies, the Persians, Goths and Vandals. It reassesses Belisarius' generalship and compares him with the likes of Caesar, Alexander and Hannibal. It will be illustrated with line drawings and battle plans as well as photographs.

Belisarius is an excellent work, useful for the serious student of the period, and a valuable introduction to the times for the novice.

Israel Book Review

Who Was Belisarius and Why Is He Called ‘Last of the Romans’?

History Hit, September 2019

Read the author article on History Hit here

The Eastern Roman empire reached its largest extent during the 6th century reign of Justinian I and Theodora. Tradition has it that the brilliance of their general, Belisarius, was the main reason for the massive territorial expansion.

Reviewed by Dr John Viggers

This biography of Belisarius by Ian Hughes depicts Belisarius as a humane, loyal, honest man, a competent politician, and a good general. Not brilliant in the mould of Alexander the Great or Julius Caesar, but competent, often lucky, and usually successful.

The book has a welcome plethora of maps (29) battle diagrams (5) and photographs (33 ). The absence of a reference section confirms that the book is aimed at the history lover and general readership rather than academics.

It is an easy read, thoroughly enjoyable, and I expect to re-read it.

Belisarius by Ian Hughes is another excellent historical biography from Pen and Sword. Highly recommended.

Provides a unique bridge between the Fall of Rome and the Eastern Roman Empire that kept the flame of Roman achievement burning until the turmoil of the Crusades.

Firetrench

The Byzantine Empire, which should more accurately be thought of as the continuing story of the Roman Empire in the east, is usually dominated by the story of one emperor, Justinian and his wife, Theodora. At this time, the empire in the west was effectively dead, but Justinian had the dream of reviving it. The man tasked to turn the dream into reality was Flavius Belisarius, a figure little known today.

Ancient Warfare, December 2010

Ian Hughes' new biography attempts to restore the name of Belisarius through a retelling of his life and exploits. Hughes draws extensively on the ancient sources Procopius and Agathias. Procopius, who is the primary source, actually served with the general as his legal advisor and private secretary and was thus an eyewitness to many key events in the story. Over the course of his relationship, however, Procopius' adulation for Belisarius turned to skepticism, which reflects in his account of the man's life and exploits.

Belisarius' life was defined by war. A soldier in Justin I's bodyguard, on the emperor's death he came to the attention of Justinian and at 27 years old was put in command of the army sent to deal with incursions by the Sassanids. He acquitted himself well during the Iberian War, with a major victory at Dara in 531. He was the highest-ranking officer when the Nika riots broke out in Constantinople and in that position was instrumental in quelling the bloody affair that saw 30,000 slain in the Hippodrome. As a rewaTd, Justinian assigned him the command of the campaign against the Vandals and in 533 Belisarius took his fleet to Africa. At Ad Decimum, near the Vandalic capital at Carthage, the Byzantines engaged the incumbent and narrowly won. Another victory followed at Tricamarum, which saw the complete surrender of the Vandals and the return of the province of Africa to the Romans. Justinian granted his general a triumph - the last ever held - in which the spoils of Jerusalem retrieved from the Vandals are reported to have been exhibited. Belisarius was elected consul the following year, 534, making him one of the last to hold this office.

Emboldened by victory in the southern continent, Justinian wanted to restore the territories of western Europe. This meant waging war against the Ostrogoths who occupied Italy. Landing in Sicily, he first had to divert to Carthage to quell a revolt there, before marching up through Italy. In 536 he took Naples and Rome. The next year he successfully defended Rome from the Goths. The war moved to Ravenna and it was from this point that Belisarius'fortunes changed. The Goths offered the Byzantine the position of emperor of the west. Belisarius accepted, entered the city and then played his trick, declaring the city as Justinian's. But it was enough to cause Justinian to doubt his general's sincerity. He was recalled to deal with the Persian capture of Syria but the campaign was inconclusive, ending in a negotiated truce. Then back to Italy he went to recapture land that had been retaken by the Ostrogoths, but the expedition ended in failure. He decided to retire from public life. He was recalled to lead the emperor's army one last time in 559 and at Melantias near Constantinople he defeated the Bulgars who greatly outnumbered his forces. Three years later, having been accused by one of his own staff under torture, he was progressive state control as these societies evolved towards centralized forms of government. The Iberian chapter is especially interesting, with a careful combination of classical sources and archaeological data that paints a vivid picture of the place war and weapons occupied in society.

Regarding arms control, chapter seven analyzes how social condemnation of ranged weapons was a means that the well-born employed to avoid their political prevalence being contested by poorer citizens. Slings and bows were, after all, considerably cheaper than the hoplite panoply or the arms and armour of a Medieval knight. Vain attempts nonetheless, as the battles of Sphacteria or Crecy corroborate. The banishment of the bearing of arms in Imperial Rome and Byzantium and of the export of arms into the Barbaricum - whether to the Germans from beyond the limes or the Saxons under Charlemagne - is also described. The end of the Western Roman Empire and the birth of the 'Barbarian' kingdoms meant a return to the importance of the individual bearing of arms, the ius gladii ferendi - "right to bear sword". Only in the Modern Age would this right be contested by states that try to consolidate their power by establishing a state monopoly on arms. But old customs die hard, and as the author states the recurrence of legislation trying to regulate arms, shows how it continued to be a problem. A final chapter analyzes the appearance of gunpowder weapons, and their relation to the progressive affirmation of modern states, although the author thinks that this did not mean a military revolution as held by others such as Geoffrey Parker. According to Ouesada, this revolution only took place at the end of igth century thanks to technological developments.

This is a refreshing book that presents a coherent picture on an uncommon topic, and with an acute epilogue that points to questions such as the individual ownership of arms in 21st century democracies.

charged with conspiracy to kill the emperor and stripped of his titles. Justinian, however, investigated the affair, found him innocent and restored Belisarius to the imperial court. He died in March 565.

The challenge for a biographer of a lesser figure in history is to shine the light upon the subject who is all too often obscured by the shadow of the greater personages he serves. In this Hughes has done the best he could with the extant sources. Belisarius' exploits are well discussed, but the man remains remote. Hughes sums up his subject as "as a man who was far above average in his military ability and very far above others in his moral integrity". Comparing the Byzantine general to Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar the author concludes Belisarius was not their equal,

but "not far below" them either. Perhaps more appropriate men to compare Belisarius against, I would suggest, would be P. Cornelius Scipio Africanus, M. Vipsanius Agrippa, Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus, Gn. Domitius Corbulo or Trajan. All were competent and popular generals who brought their nation glory. Belisarius is known as "the last of the Romans": it was his luck to be born into an age when it was still possible to dream of restoring ancient glories but holding them would prove as transient.

The book is profusely illustrated both with battle and strategic maps as well as sketches of arms and armour, and 33 black and white plates that enliven the text. I recommend it to all interested in the Byzantine Empire and 'Dark Age' Europe.

About Ian Hughes

A full-time author, Ian Hughes specializes in the military history of the late Roman Empire. He is the author of Belisarius: The Last Roman General (2009); Stilicho: the Vandal who saved Rome (2010); Aetius: Attila's Nemesis (2012); Imperial Brothers: Valentinian, Valens and the Disaster at Adrianople (2013); Patricians and Emperors (2015); Gaiseric: The Vandal Who Sacked Rome (2017) and Attila the Hun (2018). In his spare time he builds or restores electric guitars, plays football and historical wargames. He lives in South Yorkshire.